Aside from the fleeting call of a pileated woodpecker, the wind is the only other sound to cover my footsteps. I edge through the loblolly pines waiting to hear the gobble of a turkey that never occurs. Ultimately, I make my way back to the trailhead along the edge of a transition zone between healthy forest and something else, a retreating section of woodland.

Beyond the graveyard of fallen trees, the waterfowl of the refuge confirm that the area still teems with wildlife. An osprey circles its nest waiting for me to lose interest. As the sun disappears and the chill of early spring sets in, I depart the ghost forests.

Along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, sea level rise is accelerating the rate by which forests are vanishing—leaving remnant blocks of trees called “ghost forests.” The Delmarva Peninsula is ground zero for this environmental threat, which is resulting in the disappearance of tidal marsh habitat and coastal woodlands. In 2022, the visibly altered landscape of Maryland’s Eastern Shore and the Chesapeake Bay became a central issue for the strategic, long-term planning of NGOs, Maryland’s state government, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. But these environmental challenges facing the Delmarva Peninsula are spurring a new approach toward land conservation in this region, and it just might work.

Discovering Delmarva The Delmarva Peninsula includes Maryland’s Eastern Shore region, most of Delaware, and the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Maryland’s Eastern Shore lies within the Atlantic Coastal Plain and consists of varied habitats and wildlife—the Atlantic coastal bays and beaches and the Chesapeake Bay, to name a few. It’s a flat landscape covered by farms and a patchwork of residential development, historic landmarks, and small towns. While the coastlines are recognizably unique, Maryland’s Delmarva forests also provide key habitat for rare plants and wildlife.

The Chesapeake Bay and Chesapeake Marshlands National Wildlife Refuge Complex are home to a variety of unique plants and wildlife. In particular, the complex consists of four different National Wildlife Refuges—Blackwater, Martin, Susquehanna, and Eastern Neck. This Refuge Complex also includes other federally protected islands and parcels of land within the bay, which is also the largest estuary in North America.

The bay is famous for blue crabs and oysters and supports lots of species significant to the commercial and recreational fishing industries like striped bass, blue catfish, and menhaden. During the warmer months, numerous marine species including bluefish, weakfish, and flounder enter the bay to feed on its rich food supply.

The bay also hosts a wide assortment of birds. Audubon identifies Southern Dorchester Important Bird Area (IBA), which includes Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge as one of the largest IBAs in Maryland. This area is home to rare species such as black rail and saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrow. Other at-risk species, the full complement of Maryland’s saltmarsh-nesting birds, and nearly one million waterfowl are found in the bay.

Delmarva’s forests and marshes are also home to sika and whitetail deer, turkey, bobwhite quail, squirrel, and other game species. Hunting for the exotic, Asian sika deer is a unique alternative to whitetail hunting on the peninsula, and turkey hunters are a common sight in the spring. The bay and refuge complex are well recognized as a hunting destination for waterfowl due to the varied species and significant populations. Hunting continues to be a big part of the Delmarva culture.

A Changing Landscape It has often been said that the Atlantic Coast is one of the most at risk to the impending damage of a changing weather and marine patterns.

“Yes, this is ground zero for climate change,” Matt Whitbeck, supervisory wildlife biologist for Chesapeake Refuge Complex, told MeatEater. “Some of the world’s best researchers have come to the Chesapeake Bay to study sea level rise and its impacts.”

Whitbeck points out, however, that while sea level rise significantly expands and accelerates the loss of marsh and forest habitats, decades of erosion, flooding, a nutria infestation, and a naturally sinking Chesapeake have all contributed to altering the region.

“Most of what you see here in Blackwater is a changing landscape,” Whitbeck said. “Generally, the open water you observe within Blackwater was previously tidal marsh. The migrating tidal marsh was previously forest. And the woodlands are a mix of dying and healthy forest.”

The chilling effect is that you can observe the harsh consequences of climate change and sea level rise just as easily as you can view Blackwater’s wildlife.

Blackwater consists of approximately 32,000 acres, which includes open water, tidal marsh, and forest. Lots of native tidal marsh is lost to open water annually and Blackwater is also losing its forest habitat. An Audubon and The Conservation Fund report from 2013 concluded that “between 1938 and 2006, Blackwater lost 5,028 acres of its marsh…an average of 74 acres per year.” However, since 2006 Blackwater has lost approximately 3,000 more acres, an alarming rate of about 200 acres per year. “Without intervention, Maryland stands to lose 90% of its critical marsh habitats by 2100 under current climate scenarios,” the report concludes.

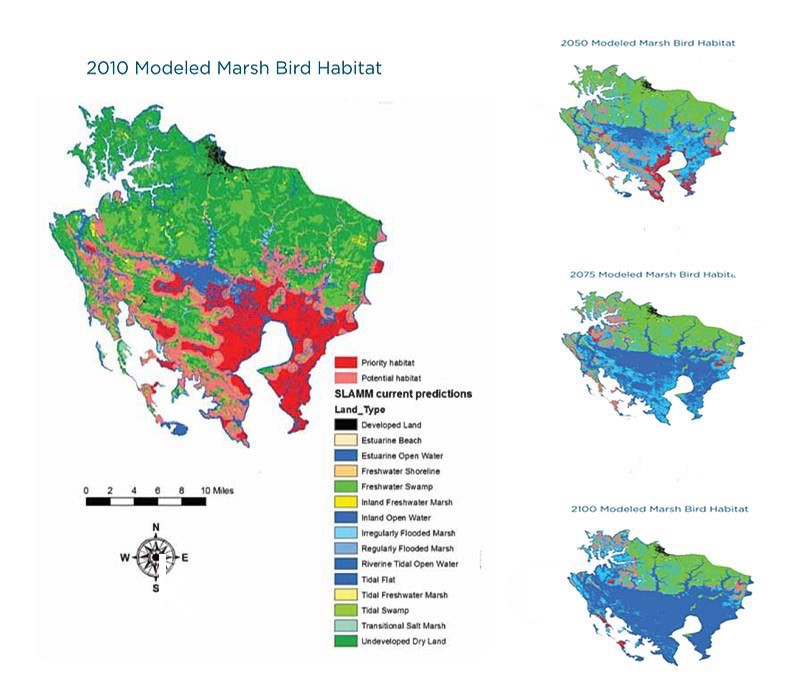

Maps from The Conservation Fund and Audubon’s 2013 Report, “Blackwater 2100.” “The maps illustrate expected marsh loss and migration of new marsh across Dorchester County in the future.” By 2075 and 2100, the maps indicate that open water will overtake most of Dorchester’s marshes and forests (including priority bird habitat).

Some new marsh will form as sea levels rise, but open water is much more prevalent in eliminating various wetland and forest habitats.

“There is a significant net loss in native tidal marsh as advancement of open water is occurring at a quicker rate than the marsh can form,” Whitbeck said. “In some areas the landscape is changing from forest directly to open water. The unnatural progression is also accompanied by invasives such as phragmites.”

Ghost Forests The Delmarva Peninsula is experiencing the full force and effect of climate change, presenting a stark foreshadowing of what can be expected throughout the mid-Atlantic and Eastern Seaboard. The spread of ghost forests on Delmarva is resulting in a substantial loss of coastal and inland woodland habitat. At Blackwater, the disappearing forest consists of mixed hardwoods and pine, specifically loblolly pines.

“This is a one-way loss,” Whitbeck said. “While sika deer will thrive, whitetail and turkey will be squeezed out.”

Aside from wildlife impacts, “coastal forests are some of the most effective habitats for reducing flood impacts and risks to communities,” he said. “These forests protect drinking water, serve as buffers for rivers and bays against sedimentation and nutrient enrichment, and provide economic and other benefits.”

In a 2019 article published by The New York Times, writer Moises Velasquez-Manoff reported on the ghost forests of the mid-Atlantic coast, including the loss of Atlantic cedar stands along New Jersey and pond pine of North Carolina. In addition to the assault on coastal habitats, the article brings attention to the problem of sea level rise killing woodlands “sometimes surprisingly far from the sea.” Similar impacts can be observed in Delmarva upriver along various waterways with tidal influence that empty into the bay.

Creeping Death “Blackwater is the poster child for sea level rise, saltwater intrusion, and land subsidence,” Maryland Department of Natural Resources ecologist Dana Limpert told MeatEater. “The acceleration of serious impacts tied to erosion, a sinking Chesapeake, and sea level rise has caused Maryland to take its leading role in addressing climate change very seriously.”

Saltwater intrusion is a subtle destructive force that gradually advances underground and attacks freshwater habitats ahead of the migrating marshes. In other words, the roots of a forest may be dying under the surface while the land above appears healthy. Limpert emphasized that saltwater intrusion also impacts irrigation and drinking water wells, occurring unseen potentially before a landowner knows to react.

According to Limpert, erosion and sea level rise have wreaked havoc on the Chesapeake’s islands, including those inhabited by people. Abandoned Country echoes these concerns, noting that places like Deal Island are facing tough hurdles due to various issues, including rising waters. Deal Island is described as an icon of bay culture with a 400-year-old heritage. However, the community already has economic challenges, a declining population, its land mass shedding numerous acres annually due to erosion, and “the rising seas threaten to accelerate that rate.”

As for generally uninhabited islands, Limpert explained that out of approximately 29 breeding islands that once existed in the bay used by colonial nesting waterbirds, only four islands remain.

Innovative Conservation Despite all of these uphill battles, losing hope is not an option.

A variety of organizations are invested in the future of what’s been called “the Everglades of the North,” including the Navy, USFWS, Maryland DNR, The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Shore Land Conservancy, The Conservation Fund, Ducks Unlimited, Audubon, Chesapeake Conservancy, and others.

Various techniques are being employed in the region to combat the disappearing marshes and forests. One novel project involves the construction, placement, and monitoring of nesting platforms for Maryland’s state endangered colonial nesting waterbirds. Maryland DNR-WHS is providing technical assistance, materials, and funding through federal Pittman-Robertson funds and is partnering with Audubon and the Maryland Coastal Bays Program.

Another project involves much needed assistance to the residents of Deal Island. Audubon is working with federal, state, and local agencies to restore 75 acres of land on Deal Island by using dredge material from the nearby Wicomico River. The goal of the project being to raise the salt marsh elevation, which will promote growth of native salt marsh grasses and protect against further erosion.

Land trusts are another solution that conservation strategists are taking advantage of.

“Land trusts are acquiring land now that in 50 years will be waterfront property and will provide for migratory pathways for plants and wildlife,” Joel Dunn, CEO of Chesapeake Conservancy, told MeatEater.

He agrees that one strategy to address the loss of tidal marsh and coastal forests is to preserve land, whether by easement or acquisition.

“Our organization, in partnership with [other organizations] and Maryland DNR, have conserved numerous parcels and thousands of acres over the last eight years,” Dunn said.

Indeed, land conservation goals for Chesapeake Conservancy are grand, seeking to follow the 30 x 30 plan of 30% land protection by 2030 for the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

Admittedly, however, Dunn was most excited about the more innovative approaches to conservation that land trusts support. Chesapeake Conservancy created the Conservation Innovation Center, which takes a more technology-focused approach to protecting the region’s most endangered landscapes. Through various partnerships, the CIC makes data accessible for restoration professionals, which helps to yield greater results with fewer resources. Chesapeake Conservancy is fully invested in this approach, hiring a 14-person staff solely for the CIC. Dunn calls it “precision conservation,” using specialized data to better understand the landscape and improve conservation decision-making.

Follow the Money According to Dunn, another fresh approach to advancing conservation goals is through the proposed Conservation Finance Act in the Maryland Legislature.

“The act would remove barriers for private investors interested in conservation and restoration projects,” Dunn said. “Public funding has always been critical, but private funding is available, and the Act can create a de-risked environment to employ those funds.”

An article published by Conservation Finance Network describes the act as technical change across the existing environmental regulatory scheme rather than a grand new initiative.

It may be hard to imagine how a bill of this nature can substantially increase private funding. The Conservation Finance Network article describes three key benefits. First, CFA will provide improved flexibility with lenders, e.g., low interest loans and fewer obstacles to obtaining lending for various, less typical land deals, such as conservation easements and forestland acquisitions. Next, the act authorizes and encourages Pay for Success as a procurement tool. For environmental projects, PFS is a method of financing and contracting in which an intermediary organization is retained to deliver ecological outcomes in exchange for payment upon achievement of project goals. These are fixed-price contracts in which pay is guaranteed only after a fully delivered restoration project. Private investors are becoming increasingly interested in environmental projects as the global market for carbon offsets expands to include conservation and restoration projects that otherwise may not be financially attractive. Finally, the act also provides a structure to incentivize landowners to participate in these types of projects.

Generally, the CFA provides a framework for private companies and individual investors to contribute resources toward climate or restoration related goals, thus broadening participation in the conservation economy. Many people involved with these issues are pushing hard for its passage.

Perseverance The changes we face appear insurmountable at times. Nevertheless, individuals, corporations, not-for-profits, and government agencies are exhibiting determination to address the environmental challenges ahead. Innovation has spurred a fresh approach toward land conservation to combat climate change, hopefully allowing a new generation to discover—and hunt—Delmarva.