Deer hunting, like many age-old human endeavors, is an activity that is surrounded by legend and lore. The stories that surround the tradition of hunting shape the techniques and understandings of many hunters, and for good reason. The experience and knowledge passed on from one generation to the next is an invaluable resource for all hunters.

But over time, some widely accepted hunting beliefs have been revealed to be nothing more than myth. These myths may be rooted in some version of the truth, but they’re often based on exceptional cases, anecdotal evidence, and false information. Some hunters may have a hard time accepting the fact that their grandfather or uncle’s vast well of deer hunting wisdom might have contained a few kernels of bullshit. But uncomfortable truths are just as important-maybe even more important- than trusty ol’ feel-good truths of the past. So we’re gonna knock some holes into some age-old deer hunting beliefs.

The Old, Dry Doe…

When hunters get busted by a deer who has seen, smelled, or heard them, they’ll often place the blame on a wise, old, dry doe. Supposedly, these suspicious, ancient does are past the point of reproductive fertility. Without any fawns to raise, they spend all their time looking for hunters and watching over the herd. But biologists have confirmed that does-even the oldest ones- continue to give birth until they die. Just because an old doe is not lactating and doesn’t have a fawn at her side doesn’t mean she is incapable of producing offspring. A doe without a trailing fawn suggests this year’s fawn likely died well before hunting season began. Some hunters also believe shooting these “old, dry does” is good for the herd because they aren’t producing offspring. But, chances are, next spring she’ll be raising another fawn. So you can’t really make your decision on whether or not to shoot a doe based on whether or not she has a fawn with her.

Young bucks with small antlers don’t grow big antlers…

It was long believed that young spike or forkhorn bucks will never grow big antlers. Some hunters who place a premium on giant antlers still believe these “inferior genetics” should be removed from the herd. But, it’s been proven that the primary factor in growing big antlers is time. Give a small spike a few years to grow and he’ll often develop into a trophy-quality buck.

Young bucks and fawn doesdon’t breed…

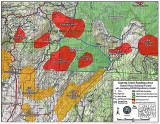

This young Nebraska whitetail buck was chasing a fawn doe in early December

This myth is complicated. Dynamics such as buck-to-doe ratios and food availability play a big role in whether young bucks and fawn does breed. Mature bucks may run themselves ragged trying to breed as many does as they can, but big, old bucks are just a small fraction of any herd’s total number of male deer. Since mature bucks can’t be everywhere at once, young bucks do have plenty of opportunities to breed does if there’s not a more dominant buck around to chase them off. Meanwhile, female fawns are sexually mature at around six months of age.They generally come into estrus much later than mature does, but they will breed during their first fall. And, if their body is in good shape, and if there’s plenty of food, and if it’s a mild winter, they can bear offspring successfully.

Rut timing is largely affected by hunting pressure, weather, and lunar phase…

Hunters often complain about the lack of rut activity if they’re not seeing big bucks. It’s common to hear that hunting pressure has curtailed rut behavior, or that the moon isn’t right, or that warm weather shut everything down. But, just because hunters aren’t seeing bucks doesn’t mean the rut isn’t happening. It might just be going on at night or out of sight in thick cover.

While deer may rut in early November in Illinois and not until January in south Texas, the peak of regional rut activity happens at the same time every year-give or take a few days. This is because deer have a strict biological imperative to time breeding correctly. The majority of does need to be bred during a very specific time so that the majority of fawns are dropped at a very specific time. This happens without fail every year in order to ensure maximum survival rates. If does dropped a smattering of fawns over various and extended periods of time during the spring, those fawns would be more susceptible to predation. But, if the vast majority of does drop all their fawns simultaneously over a concentrated period of just a few days, the impact of predation is minimized. This is because predators are essentially overwhelmed by the sheer number of available fawns.They can’t eat them all before most of the fawns are up and running. (This reproductive strategy is sometimes referred to as “predator swamping”.) Also, if the rut was actually pushed back by hunting pressure or environmental factors, more fawns would be born late. Fawns that are born late are much more susceptible to the rigors of surviving tough winters because they have less time to grow before the cold temperatures and deep snow hits. Like it or not, the rut occurs at pretty much the same time every year.

Lunar phase impacts deer movement…

This is one deer hunting belief that won’t seem to go away, and it seems to take many contradictory forms. Some hunters believe a full moon might encourage deer to feed all night and then disappear during the day, or it might spur on the rut and make every buck in the woods vulnerable. Or, a particular moon phase might shut down morning and evening deer activity but increase mid-day activity. But, again, plenty of research has shown that deer activity is generally unaffected by lunar phases. In multiple studies, deer outfitted with tracking collars have shown the moon isn’t a factor in movement patterns.Check out whitetail deer expert Pat Durkin’s take on this topic in MeatEater Podcast Ep.068.

Wounded deer always run downhill…

While this theory might be true most of the time, you can’t predict where all wounded deer will go. Personally, I’ve seen plenty of wounded animals take the downhill path of least resistance to quickly put some distance between themselves and danger. But, while most mortally wounded deer will probably head downhill, don’t ever assume that you missed a deer because it ran straight uphill. Several years ago I took a fairly long shot at a whitetail doe. After the shot, the deer ran up a steep ridge and out of sight. At first, I thought I had missed cleanly because she was moving fast and didn’t appear to be wounded. But then I noticed her tail was drooping as she ran, which is a pretty good sign of a hit. I walked to where she had been standing when I shot and bright, bubbly lung blood and small chunks of rib bone marked her path up the ridge. She had died a couple hundred feet uphill from a perfect shot through the ribcage. Since then, I’ve witnessed mule deer bucks and several elk gain elevation after being hit. And, in speaking with many other experienced hunters, it’s pretty apparent that it’s a mistake to chalk up a shot as a miss if a deer heads uphill. No matter which way a deer runs after the shot, always check for signs of a hit.

You must bleed a deer out…

- There are still hunters who feel it’s important to “bleed out” a deer after it’s been killed. There is some logic behind this practice. If an excessive amount of blood remains in an animal, it can give meat a livery or metallic taste that some people identify as “gamey.” So, it is a good idea to get as much blood as possible out of the animal’s meat. The problem is that you can’t actually “bleed” a deer out unless its heart is still pumping. If a hunter cuts a dead deer’s throat, a small amount of blood may seep out, but without the heart pumping away, the majority of the blood is trapped inside arteries, veins, muscles, and organs. Even hanging the animal upside down won’t result in a lot of blood draining from the animal. Instead of killing your deer and then cutting its throat, shoot your deer in the vital heart-lung area. In this case, the animal will fully bleed out within seconds.

All hunters should take advantage of the experience and knowledge of other hunters. But, be aware that relying too heavily on certain hunting beliefs might be hampering your success in the field.

Brody Henderson

Brody Henderson is a hunter, fly fishing guide, writer, wilderness production assistant for the MeatEater television show and MeatEater‘s editorial contributor

Shop

Sign In or Create a Free Account

Related

Big Game

Breaking from Tradition: Debunking Deer Hunting Myths

Hunting

Hunting for Information: A Tale of Two Deer