Tall tales. Yarns. Fish stories. Bullcrap. Whatever you call them, half-true or entirely fabricated stories have been favorites among hunters, probably since the first nomadic peoples started chasing animals with pointy sticks.

The great thing about tall tales, and why they’ve stuck around so long, is that they can be true even if they aren’t strictly accurate. At least they can point to something true, which is exactly what Thomas Bangs Thorpe does in his famous short story, “The Big Bear of Arkansas.” Thorpe’s story is a classic fish tale, but its themes are instantly recognizable to any hunter who’s been caught with their pants down in the wilderness—literally, figuratively, or, in this case, both.

If you don’t want us to spoil the ending, you can read the whole story here. It won’t take more than 10 minutes.

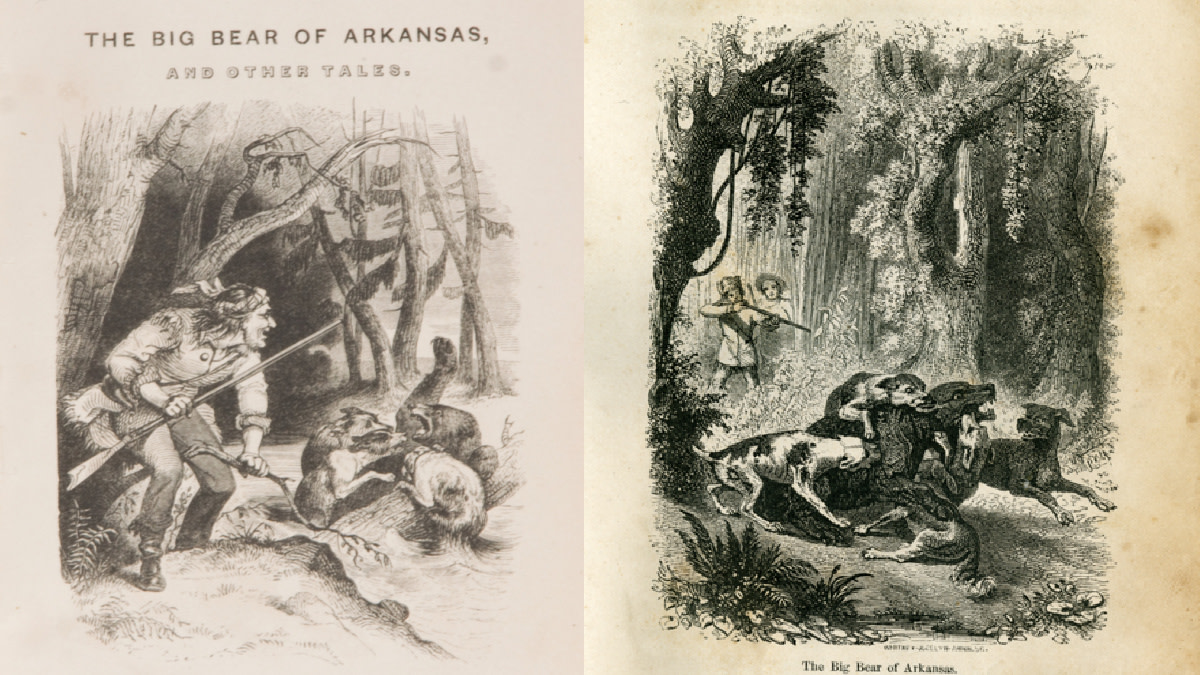

“The Big Bear of Arkansas” was first published in 1841 in a sporting newspaper called The Spirt of the Times. Thorpe’s story was instantly popular with the paper’s readership. “Big Bear” is a frame narrative told through the eyes of a passenger on a Mississippi steamboat headed north from New Orleans. The narrator sees a wide variety of colorful characters, but none more colorful than Jim Doggett.

Doggett is a larger-than-life mountain man from Arkansas bear country. He bursts out of the boat’s bar (where else?) and into the main cabin by “hallooing” (about himself).

“Hurra for the Big Bear of Arkansaw!” He stomps across the cabin, takes a chair, puts his feet on the stove, and good-naturedly addresses the cabin’s occupants, “Strangers, how are you?”

This annoys some of the passengers, but soon everyone’s face is “wreathed in a smile” as Doggett regales them with stories from “the creation State.” He explains how he once shot a turkey that weighed 40 pounds, which, when it hit the ground, “bust open behind, and the way the pound gobs of tallow rolled out of the opening was perfectly beautiful.”

In another anecdote, Doggett planted “a few potatoes and beets” that soon grew so large a stranger to his property mistook the beets for cedar stumps and the potatoes for Indian mounds. Another time, a cow stole an ear of corn, but when a few kernels dropped to the ground, the corn stalk grew so fast overnight that “the percussion killed her dead.”

“I don’t plant any more,” Doggett concludes. “Natur intended Arkansaw for a hunting ground, and I go according to natur.”

Doggett’s longest tale, and the one for which the story is known, tells of a mysterious, supernatural bear that the hunter pursued until he nearly went crazy.

When Doggett first moved to Arkansas, he was proud of his natural ability to predict the size of a bear based on the markings it left on trees. He used this ability to become the preeminent bear hunter in the area, and he describes his gun as “a perfect epidemic among bar.”

“I do my own hunting, and most of my neighbors’,” he says. “I walk into the varmints though, and it has become about as much the same to me as drinking.”

But, like many hunters high on their own abilities, it doesn’t take long for Doggett to meet an animal that gets the best of him.

This bear is enormous—at least 8 inches taller than any Doggett had hunted previously. It’s so big, he doesn’t believe it’s real when he spots its signs in the woods.

The first time he chases it, it runs him, his horse, and his dogs 18 miles before the hunting party breaks down. The bear doesn’t break a sweat.

“I was nearly used up as a man could be,” Doggett says. “Such thing were unknown to me as possible… he got so at last, that he would leave me on a long chase quite easy. How he did it, I never could understand.”

Doggett soon starts wasting away with frustration and expresses what many hunters have felt while obsessing over a particular animal.

“The thing had been carried too far, and it reduced me in flesh faster than an ager. I would see that bar in every thing I did; he hunted me, and that, too, like a devil, which I began to think he was,” he says.

He comes close to killing it only once before their final encounter, but the experience only confirms Doggett’s suspicions. Doggett’s hunting partner shoots it in the head, but the shot has no effect. When Doggett has the chance for a shot, his gun malfunctions and he can’t find another percussion cap.

When cornered by Doggett’s dogs, the bear leaps over the ring of canines and swims across a lake to an island. But when the hunters finally catch up, they realize the dogs have been chasing the wrong bear. Somehow, Doggett’s bear switched places with another bear, and they kill the wrong animal by mistake.

Doggett finally resolves to “catch that bar, go to Texas, or die” (a fitting ultimatum for an Arkansas man), as he prepares for one final encounter with his nemesis.

But the day before he plans to make his hunt, something unexplainable happens.

Doggett goes into the woods near his house to take a deuce. He brings his rifle and his dog along with him “from habit,” and as he is “sitting down also from habit,” he spies the bear less than 100 yards away.

The bear walks toward him, and Doggett stands and fires. The bear yells, wheels, and falls to the ground.

Doggett tries to run after him, but trips over his “inexpressibles,” which, he helpfully explains, “either from habit, or the excitement of the moment, were about my heels.”

The bear has died by the time Doggett reaches him, and he’s so large that Doggett makes a bedspread that is wide enough to cover the bed and leave several feet on each side to tuck up.

But Doggett isn’t satisfied. He can’t explain how the bear eluded him so many times, and he can’t understand why the bear gave in so easily at last.

“It was in fact a creation bear,” Doggett concludes. “My private opinion is, that that bar was an unhuntable bar, and it died when his time come.”

In a moment when Doggett could have doubled-down on his bear-hunting prowess, he expresses doubt in his own abilities. The bear humbled the mountain man, and most hunters have been in Doggett’s shoes. Far from the macho, bloodthirsty caricature of pop culture, most hunters I know approach the natural world with Doggett’s mixture of awe, befuddlement, and appreciation.

Just a few lines after calling the creation bear “a devil,” Doggett says, “I loved him like a brother.”

Doggett’s tale might “smell rather tall,” as one of the boat’s passengers points out, but the mixture of love, frustration, and humility the hunter voices about the animals he hunts couldn’t ring a truer note.

If you haven’t already, check out the full story here. It includes lots of great tall tales I didn’t get to cover.