Two years ago, a pair of golden eagle chicks were tagged in Alaska’s Denali National Park. The birds were fitted with satellite tracking equipment as part of a study being carried out by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey and National Park Service. Their goal was to get a more nuanced look at the migration of golden eagles, which regularly make excursions spanning thousands of miles across the continent.

The first golden eagle died of natural causes before it turned one year old. This is surprisingly common, as it’s estimated that 70 to 80 percent of eagles die before reaching adulthood at five years old. Fifty percent of those die within the first 12 months via falls, starvation or siblicide (when one sibling kills another).

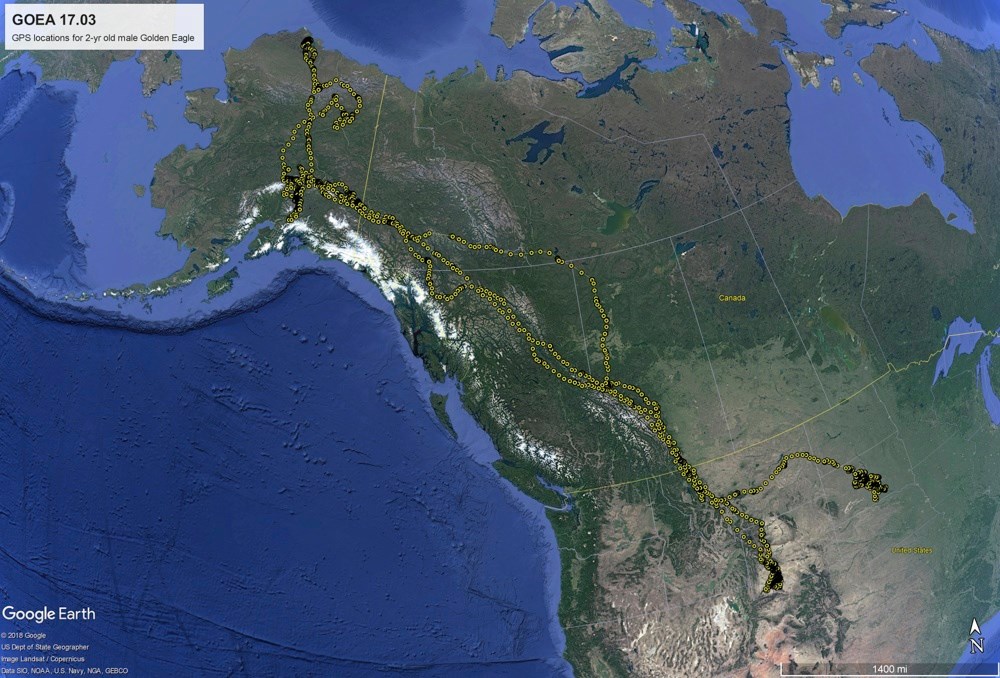

The second golden eagle was on track to beat the odds. At two years old, it had already travelled as far north as Alaska’s arctic coast and as far south as Colorado’s Rocky Mountains. While most golden eagles stay in the Rockies during winter, this young male had other plans.

In early fall, the eagle came upon the Missouri River while passing through Montana and changed its course. It followed the river east to North Dakota, and then south to South Dakota. It showed up in Pierre in October and remained in the area through winter.

“This is the first one I’ve tagged that made a left turn into South Dakota,” said Steve Lewis, a USFWS biologist, in an interview with the Capital Journal. “It was really exciting.”

However, that excitement was short-lived. Four months after the bird arrived in the state capital, biologists received the dreaded “dead” signal from the eagle’s GPS. Researchers recovered the eagle on the edge of a shelter belt on private land, and x-rays revealed the carcass was littered with shotgun pellets.

Wardens in the area are now on high alert, as this is the fourth eagle killed or wounded in central South Dakota in the last five weeks.

Hasn’t Always Been Poaching

Killing an eagle carries a max penalty of a $5000 fine and one year in jail. The birds are shielded by The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, which was created in 1940 while raptor numbers were plummeting. The law prohibits “the take, possession, sale, purchase, barter, offer to sell, purchase or barter, transport, export or import, of any bald or golden eagle, alive or dead, including any part, nest or egg.”

It’s hard to fathom that just a few decades prior some agencies had bounties on eagles.

In Alaska, the state where the birds are most abundant today, the government once encouraged residents to kill eagles. This came during World War I when the nation was on the verge of a depression; fur farmers were complaining that eagles were killing their varmints as they’d leave the den, and commercial fisherman pleaded that eagles were eating mass quantities of spawning salmon.

The state responded with the Alaska Bounty Law in 1917, which offered $.50 for a pair of bald eagle feet. Homesteaders took advantage of the payment, especially when bounties rose to $1 in 1923.

The gloves were off as residents took eagles by boat, horseback and foot. Hank Johnson, the most infamous eagle hunter, devised a trapping system where he would bait the top of poles with rotting fish. Eagles would become immobilized after landing on the pole, and Johnson could easily dispatch of the birds thereafter.

In total, more than 115,000 eagles were killed by hunters between 1917 and 1952, for a total payout of over $100,000. Accounting for inflation, that’s nearly $2 million today.

Old attitudes die hard, though. Even as agencies adjusted regulations to protect the birds, golden and bald eagles were still being persecuted. In 1966, the USFWS declared, “illegal shooting continues to be the leading cause of direct mortality both in adult and immature eagles.” In 1984, the National Wildlife Federation ranked poaching as the number one cause of eagle death, followed by powerline electrocution, collisions in flight and poisoning.

Black Market

Motivations for killing eagles aren’t hard to determine. Those who shoot eagles and leave them lay are usually doing it for the thrill or consider the birds a nuisance. Although the “shoot, shovel and shut-up” mentality is often attributed to ranchers in the West, headlines from all over the country show this is a nationwide problem.

A landowner in Virginia shot and ran down a bald eagle with his ATV that he claimed was “taking fish from his pond.” A man in New York shot an eagle that was feeding on a deer carcass, even though he claimed he thought it was a turkey vulture (which are also a protected species). A homeowner in Pennsylvania killed a bald eagle that he feared would harm his barn cats. Those are cases from just 2018 alone.

Although wardens in South Dakota are unsure if the recent eagle shootings are related, they have good reason to be suspicious.

The area was recently home to the largest documented “chop shop” for eagles. In 2017, 15 people were indicted for illegally trafficking eagle carcasses, feathers, parts and handicrafts. The ringleader, who declared himself the “best feather man in the Midwest,” was identified as Troy Fairbanks of Rapid City, South Dakota.

According to legal documents, Fairbanks had sold an undercover agent thousands of dollars worth of eagle parts, including a head for $250, wings for $600 and a tribal headpiece made of feathers for $1000. Officials estimate that about a hundred eagles—bald and golden—made up the parts seized in Project Dakota Flyer.

While eagle parts play an important role in Native American religions, the black market that values these birds is more sinister than that. Much of the illegal trafficking that takes place is due to demand for Native American regalia for art collectors in North America and Europe. There are also buyers within the reservations that use the feathers in dress for competitive powwows.

“When they put prize money on the powwow, it opened the door for exploitation,” said Harold Salway, an Oglala Lakota headman, in an interview with National Geographic.

Native Americans can acquire eagle feathers through legal means, such as the National Eagle Repository in Colorado. At the government-run facility, researchers examine about 75 eagle carcasses a day that are sent in by state agencies, private citizens and eagle rehabilitation centers. After a summary is written, parts are sent to Native Americans in order of request. In 2015, nearly 4000 people applied, which explains why some applicants wait in line for years.

Other Concerns

While serial poachers often get the most attention from the public, there are much bigger holes in the bucket that is eagle recovery. Biologists aren’t sure how expansive the black market for eagles is, but they do know that wind turbines, power lines, habitat loss and lead poisoning are killing thousands of raptors each year.

Still, killings like the recent cases in South Dakota are alarming.

“The threats are cumulative in their impact,” said Michael Hutchins, former head of the Bird Smart Wind Energy Campaign, in an interview with National Geographic. “Any exploitation of animals which is not controlled is problematic.”

Investigators admitted that poaching cases like this are difficult to solve, but are offering a $2500 reward for information leading to an arrest. If you have any knowledge, you’re urged to call 1.888.OVERBAG.

Feature image via Wiki Commons.