Wyoming Grizzly Hunt Update: Judge Rules Against Delisting Bears

In what has been the biggest wildlife management story in the U.S. since the on-again, off-again, on-again delisting of wolves in the three state region surrounding Yellowstone National Park, grizzly bears will remain federally protected under the Endangered Species Act. After almost a month of delays, a federal judge ruled against delisting the bears and allowing proposed grizzly hunts in Wyoming and Idaho. For hunters and wildlife managers, the decision is disappointing, but not entirely unexpected.

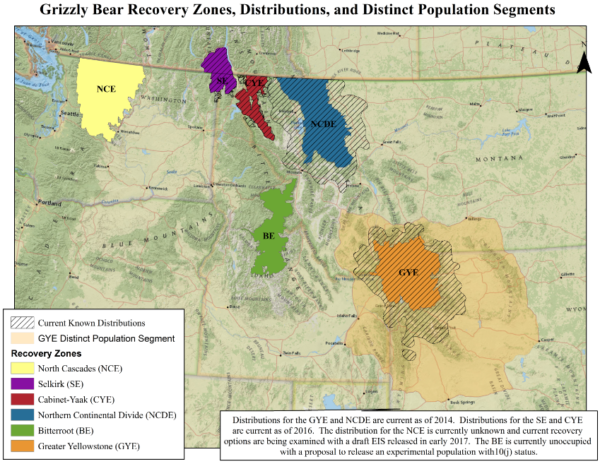

When an announcement was made last year by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to turn over management of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem distinct population segment of grizzly bears to state fish and game agencies, and in turn allow limited hunting, a legal battle over the matter was all but inevitable. Anti-hunting animal rights groups and some Native American tribes have argued that the current population could not support killing even a small number of grizzlies without endangering the longevity of the species. But both the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and state wildlife managers in the Yellowstone region believe grizzly numbers are healthy and fully recovered, and that it’s likely that the bears have reached, and possibly exceeded, total carrying capacity in the recovery area.

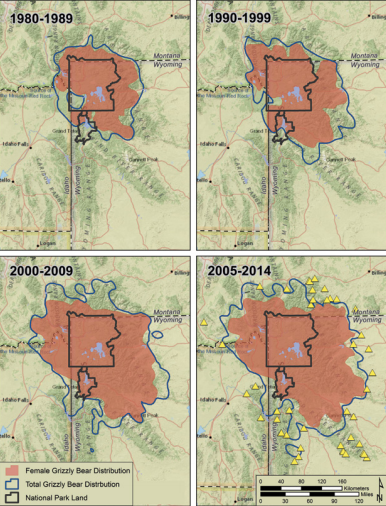

By most accounts, that is likely the case. After the population reached a low of 136 animals in 1975, grizzlies were listed as an endangered species. U.S. Fish and Wildlife mandated a recovery goal of 400 bears, which was later raised to 500 bears. That goal was met over a decade ago, and the low end estimate for their current population is now 700 bears, while some experts believe there may be as many as 1000. With hunt quotas strictly limited to one bear in Idaho, and no more than 22 in Wyoming, future grizzly bear populations were never put at risk by the proposed hunts.

While the legal battle was first and foremost related to the agency’s decision to remove federal ESA protections for GYE bears, Wyoming and Idaho’s proposed hunting seasons played a significant role in the decision. Chief District Judge Dana L. Christensen stated that, “… the (U.S. Fish and Wildlife) service’s analysis of the threats faced by the Greater Yellowstone grizzly segment was arbitrary and capricious because it is both illogical and inconsistent with the cautious approach demanded by the E.S.A.” Citing inbreeding due to lack of genetic exchange between different population groups of grizzlies as a threat to the future of the GYE bears, he stated federal wildlife managers “failed to demonstrate that genetic diversity within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, long-recognized as a threat to the Greater Yellowstone grizzly’s continued survival, has become a non-issue.”

But the judge failed to acknowledge that the Northern Continental Divide population segment just to the north of Yellowstone, which remains federally protected, is also unofficially considered recovered. With over 1000 bears and a population that is growing and both populations expanding their range outside their respective recovery areas, genetic exchange between Northern Continental Divide Grizzlies and GYE grizzlies is more likely with each passing year. Confirmed occurrences of grizzly bears have been documented between the two areas of occupied range since 2005.

Despite the decision, one thing is certain. This battle isn’t over yet. In fact, new legislation has already been introduced in Congress to delist the GYE bears in the form of The Grizzly Bear State Management Act. Just as it took time to win the battle over delisting wolves, it’s going to take time to win the battle over the delisting of grizzlies. The data clearly shows recovery goals have been exceeded, and if the intent of the Endangered Species Act is honored, eventually the management of the GYE grizzly bear population will be turned over to the states of Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana. And while some folks won’t ever see it this way, that is exactly what is best for grizzlies.