There’s a difference between book smart and bar smart. You may not be book smart, but this series can make you seem educated and interesting from a barstool. So, belly up, mix yourself a glass of LMNT Recharge, and take notes as we look at how John Chapman changed bar rooms forever. Powered by LMNT.

The world knows two different Johnny Appleseeds: the Disney version and the real version. The fictitious Johnny traveled the Midwest with a tin pot on his head and seeds in his pocket. As he wandered the Heartland barefoot, he’d cast out apple seeds to spread his favorite fruit.

The real Johnny Appleseed wasn’t all that different.

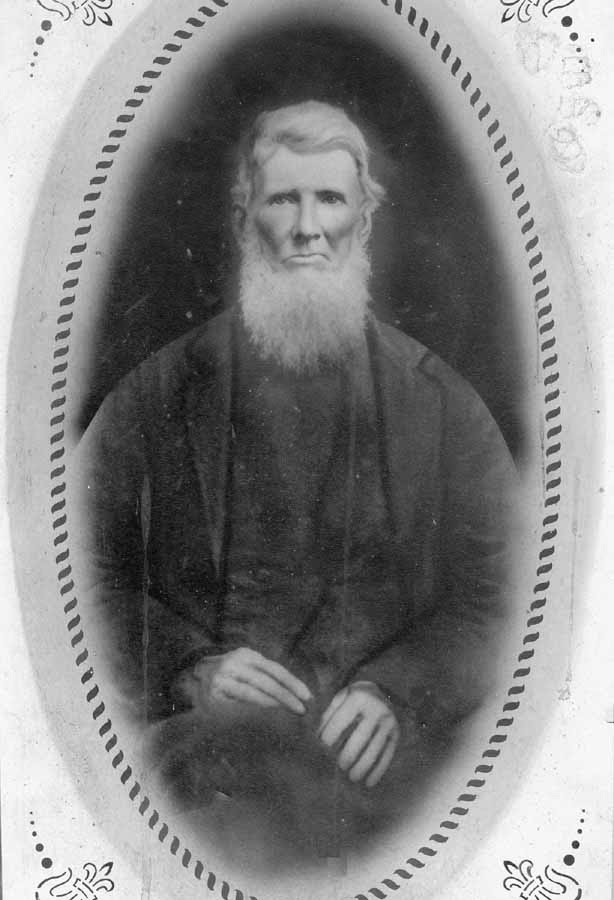

John Chapman, who went on to be known as Johnny Appleseed, was born in Massachusetts in 1774. At 18 years old, he left his home outside of Boston to explore America’s new frontier. His early years aren’t well documented, but his life’s work as a conservationist, entrepreneur, and nomad has become legend.

The same year Chapman headed west, the Ohio Company of Associates devised a plan to give 100,000 acres of land to potential settlers. This piece of earth was known as the “Donation Tract,” which was gifted to homesteaders to encourage trade and buffer the East from “Indian intrusions.” Anyone who wanted to claim their free 100 acres had to prove that they were committed to the property by planting 50 apple trees and 20 peach trees. The Ohio Company’s reasoning was that it takes a decade for an apple tree to mature, ensuring that settlers would stick around long enough to realize the literal fruits of their labor.

Chapman was a savvy businessman and saw an opportunity where others didn’t: If he claimed as many parcels as possible and planted the required trees, he could then turn around and sell the orchards to tardy frontiersmen. So, that’s exactly what he did.

Chapman spent most of the late 1700s and early 1800s as a homestead flipper, if you will. But unlike the animated Johnny Appleseed that indiscriminately scattered seeds, Chapman was methodical with his propagation. He’d use barbed-wire fence to deter deer and thieves and had an incredible knack for anticipating where settlers would arrive next. He always managed to stay just ahead of the wave of homesteaders, bettering the land and turning a buck along the way.

Another detail children’s books ignore is that Chapman’s apples tasted terrible. He was growing “spitters,” a folksy name given to apples that were so tart that you immediately wanted to spit them out after a bite. This was because Chapman didn’t graft his trees—a technique that joins two plants together to form different fruit. In those days, the only way to produce a sweet apple was by grafting, which requires the grower to create a wound in one plant and insert tissue from another plant into that wound.

It wasn’t out of laziness. Chapman was a member of the New Jerusalem Church, a budding religious group influenced by the writings of Swedish theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. One of their founding tenants was that all animals and plants are living things and shouldn’t suffer. This is why Chapman objected to grafting, instead planting his orchards straight from seeds.

Settlers still found use for the bitter fruit, though. Cider, which was one of the nation’s most popular drinks in the early 19th century, could be fermented from the inedible apples. It was a staple of every American’s diet because it was considered safer to drink than water.

“Hard cider was as much a part of the dining table as meat or bread,” Chapman biographer Howard Means wrote in “Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story.”

There’s no telling how many kegs of cider Chapman’s apples produced, but his trees most certainly outlived him. By time Chapman died in 1845, he had already gained the moniker Johnny Appleseed and become a local legend.

However, his legacy was all but lost during Prohibition. When the government outlawed alcohol in 1920, part of their strategy to eliminate hooch was tearing down orchards that grew sour apples. Many of Chapman’s trees were destroyed during this period, but a handful survived to see the 21st Amendment in 1933. One of the last remaining Chapman trees is a 176-year-old hardwood that’s still standing in Nova, Ohio.

Despite most of his trees’ disappearance, Chapman’s impact on the nation is still tangible. Many botanists credit him for helping create popular apple varieties we know today, like the golden delicious. This is because grafted trees produce the same apples generation after generation. By forgoing grafting, Chapman allowed the fruit to adapt and thrive in its new homes of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, West Virginia, and Ontario.

“It was the seeds, and the cider, that give the apple the opportunity to discover by trial and error the precise combination of traits required to prosper in the New World,” Michael Pollan wrote in “The Botany of Desire.” “From Chapman’s vast planting of nameless cider apple seeds came some of the great American cultivars of the 19th century.”

So the next time you tip back a hard cider, say a cheers to the real Johnny Appleseed. American bar rooms wouldn’t be the same without him.

Feature graphic via Hunter Spencer.