Not even the oaks, maples, and poplars now cloaking “Death Valley” were present in May 1929 when a fur buyer’s bodyguard fatally shot a Wisconsin game warden in a gunfight over black-market beaver pelts. Trees growing in that dell, located just outside of Ladysmith, Wisconsin, during Prohibition were later clearcut, leaving only a rockpile as the shootout’s remaining “witness” decades later.

Those rocks can’t talk, of course, but 80 years later they were hauled four miles south to the Einar P. Johnson Memorial Park on the Dairyland Reservoir. And, in 2008, above the park’s boat launch, volunteer masons crafted them into a wall to memorialize Johnson, 33, the state’s first game warden killed by gunfire.

History may never prove who fired first in that May 16, 1929, shootout. Nor will it prove who fired in self-defense, or how many times each man fired his .45-caliber semiautomatic handgun. All that’s certain is that Johnson’s killer, Aimo Maisio, shot the warden in the back above the hip, sending a bullet through his intestines and out his abdomen. Johnson then spun and fired more than once, sending a bullet through Maisio’s lower right lung, incapacitating him. But we’ll never know if that was Johnson’s first, second, third, or fourth shot.

Both men ended up nine miles southwest in the Ladysmith hospital that day, and Johnson died at 1:15 p.m. the next day. Maisio recovered to stand trial for murder six months later, but served only a 5-year term at the state penitentiary after a local jury convicted him of second-degree manslaughter. Before sentencing Maisio to “not less than six nor more than seven years in prison,” Circuit Judge James Wickham expressed disappointment in the jury, but said he was bound by its verdict and could not impose a harsher sentence.

According to a Ladysmith News article on Nov. 15, 1929, Judge Wickham said the jury gave “the defendant all the leniency possible,” even though Maisio had come to Wisconsin illegally armed (with a concealed handgun), engaged in illegal business (beaver poaching), and “stood a good chance of taking a human life” while protecting a black-market fur buyer and his plunder. The judge said Maisio might have been defending himself, but “only in the sense that he was resisting an officer.”

Who Shot First?

Warden Johnson’s partner, Alan “Swede” Hanson, 24, was the shootout’s only witness. Hanson testified that Maisio shot twice before Johnson returned fire. Hanson, who was unarmed, fled as Maisio and Johnson shot at each other from only 5 to 10 feet away by the wardens’ car. Hanson didn’t see Johnson get shot, but when he looked back in flight saw Maisio wince when a bullet struck his chest. Based on shell casings at the scene and unfired rounds in each magazine, investigators could only agree each man fired three or four times.

H.F. Duckhart, the Rusk County district attorney who prosecuted the case, thought the jury’s verdict was a miscarriage of justice. Duckhart said Maisio’s self-defense claim was a creative original, given that it “consists of shooting a man in the back.”

Jerry Carow, a retired Wisconsin game warden who has carefully studied the shooting and Maisio’s trial, won’t criticize the jury’s verdict. Neither will he second-guess the judge’s sentence nor the myriad opinions of anyone involved. Carow has spent most of his seven-plus decades in or near Ladysmith, a town of 3,146 on the scenic Flambeau River. He joined the Department of Natural Resources as a game warden in 1971, and spent 23 years (1978-2001) patrolling much of the same area Johnson once patrolled. Likewise, Carow’s father served as the area’s game warden before him, from 1946 through 1975, and often brought Jerry along when patrolling the area.

Carow has poured countless hours into conservation projects and community service since retiring. He’s also an amateur historian and has amassed over 1,700 pages of notes, faded photographs, court documents, and newspaper articles from the Johnson case and the dirt-poor Prohibition era in which it occurred. Some of those old reports and accounts align closely, but many others clash on basics like how to spell the defendant’s first and last names. For the record, his U.S. Army draft card and Ancestry.com paperwork spell it “Aimo Maisio,” not “Amio” and “Mysio.”

Carow wishes he could answer more difficult questions with certainty. “I knew all the old guys who were still around during my father’s time, but I didn't know enough back then to ask the right questions,” Carow said. “But even so, memories change over time. The Einar Johnson case was 17 years old when my dad arrived, and it was 49 years old when I started working here. And now another 45 years have passed, so who knows the real story? History is told by those who write it, but that doesn’t mean we get all the facts right.”

Writing History

That said, MeatEater will do its best. Maisio and his fur-trade employer, Lyman P. Byse, ate breakfast May 16, 1929, as guests of the Gilbertson family. The Gilbertsons’ farm on Highway J in Rusk County was just west of the road’s intersection with what is today Highway I, roughly 9 miles northeast of Ladysmith.

Byse and Maisio lived 200 miles north in Finland, Minnesota, an isolated town 65 miles northeast of Duluth and 6 miles inland from Lake Superior. Even though Maisio had a good reputation in Finland—serving as a teacher, “town officer,” and school district treasurer—he and Byse allegedly had mafia ties, and bootlegged alcohol from Canada, about 100 miles from their home.

The men worked the Ladysmith area three times previously to illegally trap beavers, put up pelts, and buy raw hides from locals, acquiring 70 or more pelts each trip. They worked under aliases, Byse calling himself “Lynn Grace" and Maisio identifying himself as “Pete Carlson.” Maisio was a skilled shooter and carried his .45 Colt M1911 semi-auto handgun in a leather-lined chest holster to ensure fast, smooth draws.

The black-market fur trade was lucrative. Maisio testified in November 1929 that Byse paid him $80 for his work, and paid locals $20 for each good beaver hide. A fair pelt price for a lawfully caught beaver was about $45. In today’s dollars, that’s $352 for a good boot-legged pelt and $792 for a lawful sale. Maisio often carried $1,000 to $4,000 in cash to ensure he capitalized on every such opportunity. Carow described how the scarcity of the era influenced poaching.

“Nobody had nothing back then,” Carow said. “This area had only been settled about 10 to 20 years earlier. People got 40 acres and built their homes from lumber they cut from their own trees. Their shared value was that neighbors helped each other survive. One family would raise rutabagas for everyone. Another raised carrots, another raised potatoes, and another raised cabbage for sauerkraut. One beaver pelt was worth more than some families’ monthly income, so you can understand why conservation might take second place to survival. That caused an overharvest of beavers, and so the state closed the season in 1929. But poaching remained common, and illegal fur-buyers befriended the Gilbertsons and many other farmers in the area.”

The Bloody Morning

Byse and Maisio rolled out of the Gilbertsons’ driveway about 7 a.m., hoping to buy beaver pelts from a farmer up the road. Even though it was mid-May, a light snow had fallen overnight, making the unpaved roads slick with mud. They drove east on Highway J and continued north from its intersection with eastbound Highway I.

As wardens Hansen and Johnson approached from the west in Johnson’s Model T, they recognized the bootleggers’ blue De Soto from an encounter the previous week. The wardens hoped the poachers hadn’t seen or recognized their car. Just in case, Johnson turned east on Highway I to throw them off, and turned around once he was certain it was safe to tail them. With luck, he and Hanson would learn where the poachers were trapping and who else they were working with.

After backtracking to the intersection, the wardens turned north and followed the bootleggers’ slipping-sliding tire tracks on Highway J about a half-mile. After cresting a rise in the slick road, they saw the De Soto stuck in the west-side ditch. The car was empty, and two sets of snowy footprints led into the trees. The wardens assumed the bootleggers had spotted their car earlier and fled into the woods to stash their beaver pelts. Johnson also noticed the car had California license plates. When he and Hansen searched it the previous week, it had Minnesota plates.

Byse soon stepped out of the woods and hurried toward them. Johnson asked why he was in the woods, and why the car had new license plates. Byse reportedly said he was simply taking a leak and acquired California plates because he would soon be moving there. Johnson said he didn’t believe either story, but Byse walked off for the Gilbertson farm to request their horse team pull his car from the ditch.

Hanson then followed the other footprints into the woods, and within 20 yards found a heavy packsack beneath a balsam fir’s low-swept branches. Meanwhile, Maisio stepped from the woods nearby and approached Johnson as Hanson lugged the packsack toward the road. As Hanson approached, he saw Johnson talking to Maisio while writing the De Soto’s engine identification number in his notebook.

Hanson began opening the pack at the roadside to verify it held pelts, but stopped when Johnson yelled: “Give him the stuff. We’re beat.” Hanson later testified that he assumed Maisio had drawn a gun, because he had seen him make a quick move into a side pocket on his coat, and tell Johnson, “Put ’em up, you dirty…”

Hanson wasn’t armed because Wisconsin didn’t issue weapons to game wardens in that era, and Hanson couldn't afford to buy one. He said he and Johnson jumped back onto the road to get behind their car. Hanson took off running when Maisio fired twice at Johnson.

“As I ran down the road, I glanced back and saw the stranger leaning against the fender of the car, and shooting. Johnson was also shooting,” Hanson said, according to the May 17, 1929, edition of the Ladysmith News. Hanson believed Johnson spun and returned fire after Maisio shot twice.

Self-Defense Shooting?

During his trial testimony, however, Maisio claimed he didn’t know Johnson and Hanson were game wardens. However, he also told investigators he had reached for his gun to hand it over to Johnson, and conceded the shooting probably wouldn’t have happened if he hadn’t been carrying the concealed gun, which was then illegal in Wisconsin. He said he fired in self-defense only after Hanson yelled, “Give it to him!,” and Johnson shot and missed three times.

Maisio said he felt threatened because he was caught between the wardens and didn’t know Hanson was unarmed. He also testified Johnson fired at him from under his left arm while retreating across the ditch. He said he didn’t fire at Hanson because, “He didn’t shoot at me.”

When the shooting stopped, Hanson continued running north up the road. He stopped at a house about 275 yards away to seek help, but found neither the owners nor a phone. Maisio, meanwhile, lay immobile with a chest wound, and Johnson—despite his grave wound—cut some balsam boughs for Maisio, covered the boughs with a blanket, and pulled the bootlegger atop it to keep him off the wet ground.

Johnson then tried starting his car with the engine’s hand crank, but lacked the strength to turn it. He staggered cross-country through the woods toward the Gilbertson farm, where Byse and two Gilbertson brothers had heard the shooting while talking outside. Arthur Gilbertson returned to the farmhouse after Byse and Ervin Gilbertson hitched up the horse team and headed for the scene. After Johnson reached the farmhouse, Arthur drove him to the Ladysmith hospital.

After failing to find help at the nearby farmhouse, Hanson cautiously headed back past the scene while staying inside the woods, well off the road. He saw Maisio atop the blanket but kept going. Byse and Ervin Gilbertson arrived at some point with the horses and pulled Byse’s car onto the road.

Byse tried lifting Maisio off the blankets but gave up and drove off as Gilbertson watched. The farmer assumed Byse would turn around at the first driveway to retrieve his partner, but Byse instead circled back to the Gilbertson farm. There he encountered Hanson, who had just arrived, and warned him not to summon the sheriff. The fur-buyer told Hanson that Maisio’s relatives had mafia connections, and they would “get him” if he didn’t listen. Byse then drove home to Minnesota.

When Johnson arrived at the Ladysmith hospital about 10:15 a.m., he told the doctor and nurse that his assailant had fired twice before he could return fire. The doctor summoned Sheriff E. Wilson, who drove to the Gilbertsons’ farm and then to the shooting scene. The sheriff found Maisio still alive but immobile atop the blanket, and drove him to the hospital.

Though Johnson had arrived hours earlier, he was in worse shape than Maisio. Johnson’s wound and cross-country trek had nearly killed him. Initial news accounts said both men were expected to recover, but Johnson’s condition turned grave after surgery.

Byse, meanwhile, secretly returned to the Ladysmith area at least twice in the following months to monitor the case and conduct more business. County authorities charged Byse with trafficking in beaver hides and being an accessory to Johnson’s murder, but he eluded capture and never stood trial in Wisconsin.

Rooting for the Bad Guy?

Public sentiment around Ladysmith had swung Maisio’s way six months after the shooting. Even though he had come there on illegal business, and had bragged that wardens would never take him if he had his gun, Maisio enjoyed partisan support during his November 1929 trial. His attorneys talked up his service in World War I, and they summoned five character witnesses from Finland, Minnesota, including two sheriffs and a local schoolteacher. All five said he was a model citizen.

And although Johnson had been an Army officer and respected World War I tank commander, and left behind a young wife and 7- and 9-year-old daughters, local rumormongers labeled him a trigger-happy, overly-aggressive game warden. People claimed Johnson regularly pulled his gun when making arrests, and assumed he had shot first.

Maisio’s attorneys, however, couldn’t produce one witness to corroborate those rumors. In contrast, several law-enforcement officers who regularly assisted Johnson with arrests testified that he never pulled his gun.

The courtroom was packed throughout Maisio’s trial, and the crowd openly sided with him. Judge Wickham often gaveled spectators to silence, directed deputies to clear people from the aisles, and ordered those without seats to leave. When the judge gave the all-male jury of nine farmers, a cement contractor, and two local merchants his final instructions, he said it didn’t matter who shot first. The judge said law officers had “the right and duty” to shoot in self-defense if a suspect draws a weapon in such circumstances.

The jury deliberated nearly six hours, and apparently needed nine ballots to render its verdict. Not once during those nine ballots did a juror vote for first-degree murder. On the first ballot, four voted for second-degree murder, five favored manslaughter, and three chose acquittal. After that, the votes grew increasingly lenient, until the jury voted unanimously for second-degree manslaughter.

After his five years at Wisconsin’s state penitentiary in Waupun, Maisio moved back to Finland, Minnesota. He eventually befriended a game warden there, and often rode along on patrols during his final 30 years. By all accounts, Maisio was a law-abiding citizen and well-liked in the community. He died at age 85 in 1978, forever claiming he shot Johnson in self-defense.

Byse avoided Wisconsin’s arrest warrants by living in Illinois and Texas for a while before returning to northern Minnesota and settling there. He regularly violated Minnesota’s fish and wildlife laws, and was arrested often in the late 1940s, but Wisconsin never prosecuted him for bootlegging furs or being an accomplice to Johnson’s killing. Byse was 70 when he died in 1967 in Lyle, Washington.

Conclusion

Warden Hanson went on to serve many years as the Ladysmith area’s full-time game warden.

A month after Johnson’s death, staff from the Wisconsin Conservation Department’s Madison headquarters visited Johnson’s widow, Evelyn, at her parents’ home in Eau Claire, where she lived with her young daughters.

After expressing condolences, the officials got down to business. In that era, Wisconsin paid game wardens their annual salary in one lump sum on May 1. Johnson died just 16 days after receiving his estimated $1,100 paycheck. The state officials told the grieving widow she must return the balance of her husband’s 1929 wages.

The state’s warden force responded privately by pooling enough money to make a one-time donation for the family’s first year without him. Evelyn remarried in 1943 when her daughters were young adults, and she died in July 1986 in Eau Claire at age 93.

Why do locals still refer to the Johnson shootout site as “Death Valley?” Even though the site is basically just a subtle dip in the landscape, death has often visited this “valley.” Carow, the retired warden and local historian, said three other people have since died unusual deaths there. One man poisoned himself with strychnine, another accidentally cut his leg with a scythe and severed an artery, and a third died in an accident inside his barn.

Byse had a knack for escapes. While serving in World War I, he was one of 2,013 American soldiers aboard the liner Tuscania, a troop ship bound for Le Havre, France, in January 1918. It became the first troop ship sunk by German U-boats. The ship sank with 201 soldiers and about 20 crew members. An article in the Feb. 11, 1918, edition of the Stevens Point Journal near Byse’s hometown in Wautoma, Wisconsin, listed him among the survivors.

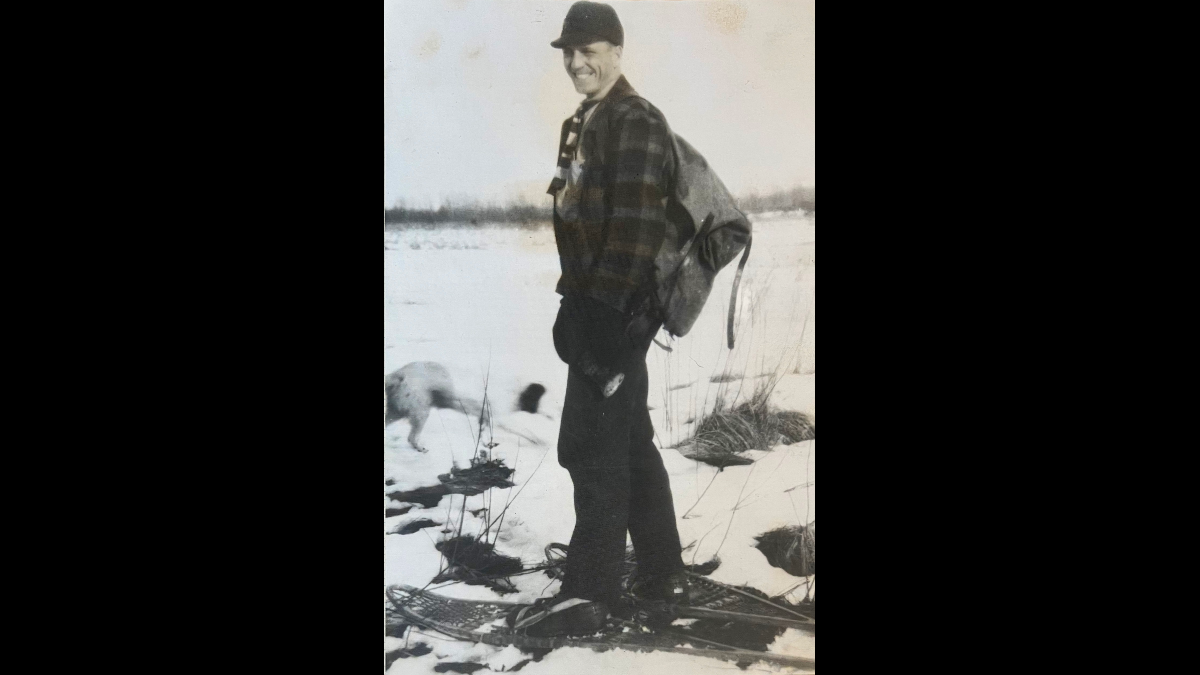

Feature image of Warden Einar P. Johnson via Wisconsin Conservation Department.