I steadfastly refused to troll for gamefish. An avid steelheader, the idea of casually lounging in a gas-guzzling mini-yacht, trusting deckhands to help me catch fish, all while sitting in a chair that I suspect my dentist designed… I was beyond disinterested.

In my mind, bill-fishing was for one of two sorts of people: the fat, rich kind who need their egos stroked, and International Game Fish Association, (IGFA) record-chasers desperate to see their names in print. I felt about as much connection to either party as a magnet does to plastic. So, in my travels to saltwater destinations, I instead chose to stalk permit, bonefish, and other species on the flats. Flats fishing seemed to be the saltwater equivalent of steelhead fishing. The patience of a hunter is a necessity. You need an awareness of subtle movement and a willingness to work tirelessly for a single shot at success. Loud engines and a team of people relying on my coordination just didn’t seem to fit the bill.

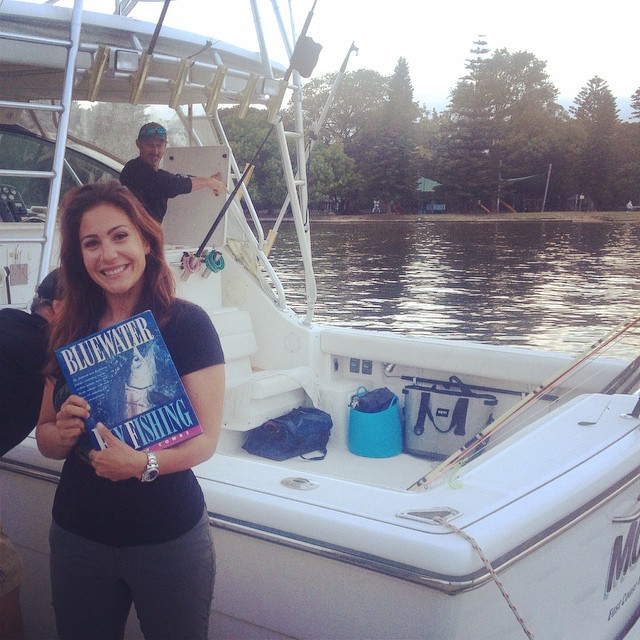

My conversion kind of happened by mistake, starting six years ago when I made the decision to exchange my Canadian winters for Australian summers. Australia’s attractions are enormous marlin, Indo-Pacific permit, giant trevally, and short plane rides to New Zealand. It seemed my new part-time home was a playground of relatively unexplored terrain — opportunity perfect for a fly fisher. While I was eager to get to the glowing, yellow permit that live north of my home in Sydney, it is the infamous billfish that are most accessible to me. Found only a short ride from the boat-launch near my house are warm currents and bait balls large enough to sustain a plethora of predators.

It was actually my husband’s enthusiasm for fly fishing for billfish that piqued my interest. Neither fat nor egotistical – and with no interest in chasing records – his entire world still seemed to revolve around the mystical deepwater beast he called marlin. I was amused by his endless excitement for the subject and so agreed to give the fish a try.

Because our boat is only eighteen feet long, it required some unique rigging. The shortage of space meant that our crew would consist of just the two of us. Unlike the charter boats, there would be no long off-shore distances traveled, and we would be the only people shouting orders at one another (nothing new there). My perception of marlin fishing was starting to change.

It was when he sat me down and drew a diagram of “how the fly-fishing for marlin game is supposed to be played” that I felt myself panic. The realization that marlin fishing is the epitome of a team effort hit me like the sickening slap of a slimy mackerel dropped on a boat deck. I realized that to do this right, I was going to have to listen.

Since that lesson six years ago I have spent countless days searching for marlin, working to tease one of these mighty animals to the surface, only to then find a new creative way to mess it all up. It would appear ol’ Murphy and the marlin had a secret meeting some years ago. So, while my success rate hasn’t necessarily been on an upward trajectory, it seems that the public’s understanding of fly-fishing for these gamefish hasn’t either.

Australia is home to the striped, black, and blue marlin. While foolish dreams of landing a blue grander (a fish over a thousand pounds) often play through my head, it is the smaller black and striped marlin that are a more reasonable pairing for fly gear and my five-foot, five-inch frame. But the truth is that all three of them absolutely terrify me.

It doesn’t take much beyond a quick YouTube search to see how billfish anglers get themselves into trouble. Poor boat-handling aside, often it is simply the sheer panic of a leaping marlin that sends anglers into damage-control mode as the fish’s sharp bill stabs at the sky, the boat, and anything that may be unfortunate enough to get in its way. I needed to learn the protocol before I could responsibly target one of them.

In short, in a chartered situation there are two deckhands (deckies for short), a captain, and a fly fisher. The captain steers the boat through fishy territory while the deckhands rig and troll teaser baits which drag and “smoke” in the white frothy water that’s churned up by the boat. The goal is to create a disturbance in the water that imitates a school of tuna (or similar school of other feeder fish). This in turn “calls” a fish up from the depths of the ocean, where it then hopefully sets its sights on the trolled bait, mistaking it as a straggling, easy meal. This is always a hectic moment — the water erupts, a bill spears the air, a dorsal fin slices the surface, and fluorescence lights up the entire backwash. When billfish get excited, their bodies turn magnificent shades of blue, green, and purple.

If the deckhand is doing his job properly, the fluorescent flash of fury is headed straight for the stern of the boat and the rapidly retrieved teaser-bait. The fly fisher awaits the fish’s approach and when the chance comes, shouts for the deckhand to get the teaser out of the way. At this moment the captain must knock the boat out of gear, the deckhand must get the teaser-bait out of the water, and the fly fisher must make the appropriate presentation to have a reasonable chance at a hookup.

And this is all just to make the cast. Granted, it’s a short cast, but what it lacks in glamour is made up for in pressure.

The angler needs to be aware of the direction the fish is swimming and try to drop the fly somewhere near the side of its head. A cast to the front of its bill results in a difficult hook-set, or an occasional lassoing. Depending on whether the angler is fishing a top-water pattern or a large streamer, the fly is either stripped or “blooped” near the infuriated fish. In the frustration of losing sight of the teaser-bait, it snaps at the nearby fly instead. Takes are almost always visible, as most of the time they happen on or just beneath the surface.

If the angler has been able to manage all of the above steps and the fish is hooked, it either greyhounds (jumps repeatedly) or sounds (heads straight for the bottom). The angler then adjusts the drag on the reel accordingly, typically reducing it to accommodate the increasing resistance of the water on the long length of fly line and backing.

For my husband and I, the routine goes like this: catch and rig baits the night before, launch the boat, run until the water turns to cobalt blue and the air temperature starts to rise, set out the teaser bait on the spinning rod, strip a bunch of fly line into a laundry basket so that one of us is ready to make the cast, bring the motor to trolling speed, stand in each corner of the stern in anticipation, stare at our bait until seabird wings look like marlin bills, and generally fall to pieces any time a fish shows up.

As word of my marlin-obsession spread through the fly-fishing world, I found that my initial negative misconceptions about trolling flies, chumming, and boredom were shared by other people who hadn’t tried it.

Such notions forced me to examine myself, looking for a reason for my endless determination. Excitement and adrenaline aside, there were two aspects of the sport that I kept returning to. After spending so many years as a solo angler whose mission was to escape other people who were equally as eager to escape me, there was something refreshing about being part of a team. Sure, a day’s float with a buddy on a steelhead river is still technically “teamwork,” but marlin fishing requires people to sync and work together on a whole different level. While marlin can certainly be caught by way of a “one-man-operation,” the fine-tuned process is best (and most safely) undertaken by several people working together. The very thought of needing others was one of my initial deterrences, but after putting in so many hours with friends, I’ve learned to love the team spirit that is so rarely found in fly-fishing.

While interaction was indeed a bonus, I knew there had to be more to my unshakable perseverance, so I dug deeper still for an answer. I found it when I asked myself why I was so drawn to my favorite species of fish: the steelhead. Steelhead rule when they enter the river systems. They make me work. They beat at my sanity, my body, and my patience. And when I land one, I’m reminded that I am simply a brief observer of its highly complex life-cycle. The marlin is very much the same. King of the ocean, there is no saltwater species more regal.

Fly fishing is a sport of growth and progression, and that’s a path many of us follow. For some, the path leads to the mountain tops, for others, it’s a meandering trail through the valleys. For me, it’s been a long trek over peaks and shorelines, and has landed me smack-dab in the middle of the ocean. So if you’ve been avoiding a certain type of fishing because you believe that it’s not for you, try it anyway. It might be the best chance you’ll ever take.