People often ask me where my favorite fly-fishing destination is. Without hesitation my answer is always the same: Bolivia. Bolivia is one of the most remote countries in the Americas. With 60% of its population being pure Native American ancestry, it has more indigenous people than any other country in North or South America. The golden dorado that live there are aggressive, hungry, huge, and found in clear rivers far from civilization. They possess qualities of other world-class fisheries, packed into one perfectly sculpted metallic gold body; jumps like tarpon, eats like taimen, runs like steelhead, plus the ability to sight-fish for them in clear water. One might even argue that they are the king of sport-fish… which is exactly what 19th century angler, John Hill, did.

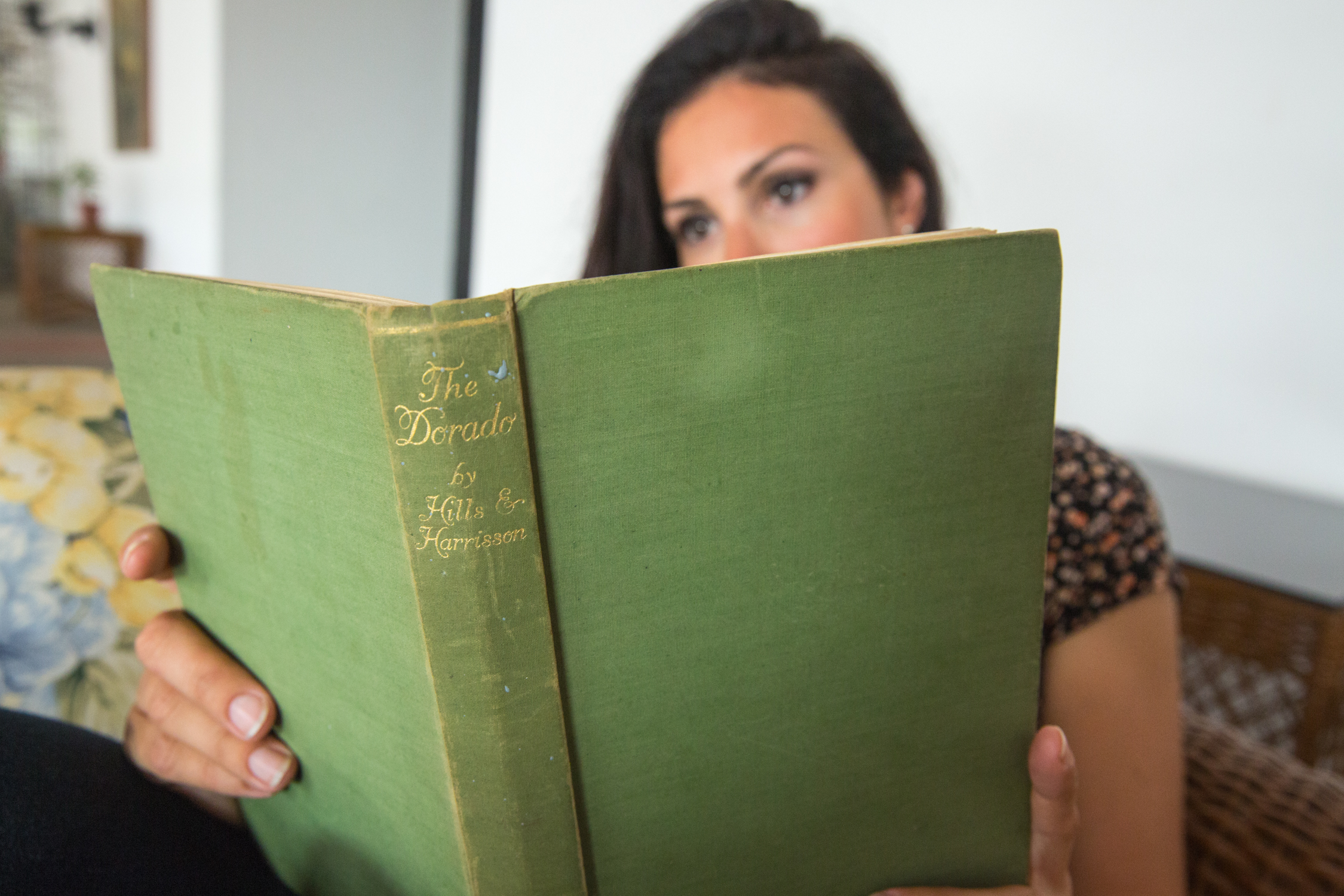

In 1923, Hill published a book about his adventures in South America. An Englishman, he was versed in fishing for one of history’s most revered species: the Atlantic salmon. His book makes note of the comparisons between the two species. It was this book that lead me to the jungles of Bolivia. More specifically, it was Marcelo Perez, owner of Untamed Angling, who planted the idea and extended the invitation. He had read Hill’s book comparing the species and was determined to showcase that large dorado can be caught on two-hand (Spey) rods, much like they fish for Atlantic salmon in the UK.

Over a decade ago, Marcelo’s company partnered with a group of Amazonian natives and local authorities to form a fly-fishing program that would be sustainable and beneficial to everyone involved — fish included.

“These are virgin, hidden, and gorgeous environments where nature stays untouched like it was thousands of years ago. Normally these areas are Indian Territories, National Parks, or both, so I had to create a new kind of sustainable fly fishing model to make it happen. Logistics are a nightmare (not for the guests); we share the benefits with the natives, deal with political issues, practice strict catch and release with small groups of anglers in huge areas, and use alternative energies as much as possible.”

I was in, but knew from the get-go that my major obstacle was going to be casting large flies on a two-handed (Spey) rod. While anglers today will argue that “the kitchen sink” can be cast on condensed shooting heads, what many of them fail to consider is the sheer mass the fly takes up as it sticks to the water during the cast’s ‘anchor’. For a Spey-cast to be properly executed (meaning with ease and minimal disturbance to the water), the fly-line needs to be aligned in what is called the 180 degree principal. Flies of excessive length can make this task tedious, if not impossible. There’s also the issue of climate. Typical Spey lines aren’t made for the humid heat of the jungle, so single-hand rods and the basic overhead cast often tend to make the most sense on such a trip. I’ll let the video tell the rest of that story. But what isn’t told in the film — or in most write-ups about fly-fishing in Bolivia — are things I’d either heard about or experienced while there; things I found as intriguing as the fishing itself.

Sabalo:

In Bolivia, golden dorado feast on a small schooling fish that look very much like a North American freshwater whitefish. The species is actually Prochilodus nigricans, but the commonly used Spanish name for them is sabalo. Sabalo are a reliable food source for everyone in the area. Natives hunt them with homemade bows and arrows, and dorado feast on them, often herding them close to shore where I found myself sprinting to partake in the action. Landing a fly in such a feeding frenzy is a guaranteed hook up. The water froths into a mess of white foam, yellow fins, and silver scales.

Candiru:

“Don’t pee in the water”, I was warned. Jeremy Wade fans around the world excitedly messaged me to tell me about a parasitic freshwater catfish, also known as a vampire fish, that could enter the human urethra via the urine-stream. Centuries of lore told tales of a skinny, transparent eel-like creature drawn to the smell of human urine. Adding to the dramatics, some writers have even gone so far as to say that it would leap clear from the water to deliberately lodge itself into the human penis. When I mentioned this to Marcelo, he laughed at me and told me to stop watching so much television. While there are indeed candiru in the river, there have been zero confirmed cases of any swimming through urine to lodge themselves into urethras (though there have been several confirmed cases of candiru swimming and getting stuck in the vaginas of women bathing in the river). But rare instances aside, it is the dorado that receives the most attention from this parasite.

The small catfish feasts upon the blood from the gills of its host — which are typically larger Amazonian catfish — however, they’ll prey on the dorado as well. Marcelo told me he’s seen it many times before. He told me it happens when the water becomes muddy; the candiru enter the river system in groups and swim into the gills of the dorado (or any vulnerable big fish) when they are hooked up and fighting on the end of the line. He said they latch onto one of the fish’s main arteries, creating a wound that never stops bleeding.

I reached out to Brazilian biologist, Alec Zeinad, to see if I could pick his brain on the matter. He explained that the candiru family, Trichomycteridae, has 307 species distributed through eight subfamilies, and that the Tsimane river basin, the Madeira, has more than thirty species of them. He specified that the subfamily, Vandelliinae, is a parasitic species that attacks a large variety of fish — dorado included. He clarified that while most attacks do tend to occur in murky water, they will also attack in clear streams. And speaking of clear streams, he confirmed that while any “candiru attacks” on humans were either myth or accidental, the hematophagus (blood-sucking) candiru does indeed follow the scent of urea and ammonia excreted from the gills and urinary outputs of its potential host. Just to further shiver my spine, Alec reminded me that the candiru are one of many species known to attack the golden dorado after it’s been released by an angler.

Dorado:

One group that doesn’t eat the dorado, however, are the Tsimane Indians. They consider the dorado to be fellow-hunters, and are therefore sacred. As the dorado feast on sabalo, they herd them close to the shore and within shooting range. The dorado (meaning ‘golden’ in Spanish) can grow up to 75 pounds. Females grow larger than the males, and can lay up to 2 million eggs when they reach maturity at around four years old. They travel an average of 250 miles to spawn. Dorado are opportunistic feeders and will eat virtually anything that crosses their path. Their diet consists mostly of fish, but they have also been recorded eating crustaceans, frogs, rodents, lizards, large bugs, and even birds!

Mosquitos:

“Expect to be carried away by mosquitoes, and be sure to get your vaccines”. I’ve seen the damage a mosquito can do. On a past trip to Argentina, I saw a man whose arm had all but rotted off. Malaria, Dengue Fever, Yellow Fever and the Zika virus, I don’t mess around when it comes to the world’s most dangerous insect — I headed straight to the travel vaccine clinic. Suggested vaccines are typhoid, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, yellow fever, rabies, and influenza. I was there in August and didn’t get a single mosquito bite, but I was absolutely destroyed by a small black fly that has a bite much bigger than its bark. I never felt one nip me, but at the end of the day was feeling the itch more than any other flies I’d encountered before (New Zealand and Quebec flies included). Long sleeves are a must, though lodge manager, Chucky, has a remedy that is shockingly effective. He soaks cloves in alcohol for several days, then mixes in eucalyptus oil and transfers the mixture to a spray bottle. We applied generously and, while we reeked like alcoholics, the bugs mostly left us alone.

Jaguars:

As the guides ate lunch in the heat of the day, I practised shooting one of the local handmade bow and arrows. Head guide, Juan, patiently explained what each arrow was for. The blunt tip was for birds, the serrated edge was for fish, and the spear tip was for jaguars. I learned that a single arrow wouldn’t kill the enormous cat, rather multiple arrows in a group effort by the tribe is what is necessary to bring the spotted beast down. One of the men in our crew was covered in scars from a jaguar that attacked him several years earlier. The jaguar, said to be the largest of the cats (after lions and tigers), had grabbed him by his shoulder and dragged him out of his slumber as he slept beside his wife. The rest of the men awoke and, together, killed the jaguar. The man’s arm, shoulder, and neck looked like he’d been stabbed repeatedly by a sharp knife. Frankly, he is lucky to be alive. Jaguar prints stamped themselves into the sandy shores along the river and, much like cougars in North America, we knew we were being watched, but only had one brief sighting.

Butterflies:

I’d never seen so many butterflies. They flew around us as though we were in a dream, each one of them different from the last. A recent scientific expedition in the area identified over 1000 species of butterfly — to put it into perspective, there are only 725 species in North America. They fed in abundance on bird and animal poop, and while I tried to tell myself that they continued to land on me because I smelled delicious, their obvious appetite for fecal matter reminded me that I could probably use a shower.

Extreme Rain:

During our upriver camping adventure, a light rain very quickly turned into a torrential downpour. River levels went from knee-high to shoulder-high in several hours. We raced downstream to get back to the dugouts and had to strip our waders off so we could cross the river safely. The dugout canoes are made of Öchoo and take around ten days to build. Once ready to launch, one man stands in the front of the boat, while another sits in the back. They both pole and work together to manoeuvre.

Coca Leaves:

The Tsimane people’s cheeks bulged with large bunches of dried coca leaves. The leaves themselves, used to make the illegal narcotic, cocaine, are a major part of Bolivian culture. Used as an affordable stimulant, the lightweight leaves are easily dried and packed into small bags. I don’t think I saw a single local without a cheek looking like it was housing a golfball. Dating back to ancient mummy times, coca leaves have been a part of human life for millenniums — even the famous Coca-Cola used them in their original recipe (the company substituted the ingredient in the early 1900’s). So I decided to give it a try. Within minutes, my cheek became numb and I felt as though I’d just slammed a strong coffee. Personally, I prefer a coffee rather than the numb face and abundance of foliage stuck in my teeth.

Pacu:

The pacu, a relative of the piranha, is an omnivore that primarily feeds on nuts and berries. The pacu’s teeth are vastly different to the piranha’s; they have flat crushers and incredibly strong jaws. Deemed by many as the “permit of freshwater”, I’d heard they fought harder than almost any other fish in the river. I’d targeted them before by dead-drifting round, apple-green foam flies made to look like falling chontaduro berries (also known as peach-palm fruit). So when we found two large pacu cruising the gin-clear channels of one of the rivers near camp, I threw my black dorado fly at them in hopes one might take. Competition between the two ensued and one of them lunged and ate the streamer.

We still had two nights of camp left and our protein was running low, so I was more than happy to take it for lunch. Its mouth looked as though it would start talking to me as I bled it out on the shore… creepy to say the least. But in all my years of eating meat, I have yet to taste something as delicious as the pacu. Its meat was fatty and its rib bones were coated with a pork-like sweet, yet savoury, flavour that melted in my mouth.

Caiman:

Dozens of Caiman could be counted sunbathing on the shores of the Pluma river. Admittedly, as I waded up to my waist in the murky water, I didn’t realise the river was full of them until we boated around the corner. I felt like I was going to be sick as I watched the large creatures slither into the water, but was quickly reassured that these freshwater caiman only eat fish and that I was quite safe. I’m unsure which species of caiman are in the Pluma, but have been reminded that the black caiman is an opportunistic feeder that will hunt humans, jaguar, tapir, and anything else it can get its jaws on.

Freshwater Stingrays:

The one species I was extremely mindful of was the freshwater stingray. Growing up to five feet long and 500 pounds, I’d heard nightmares from people who had been impaled by the large animal’s tail. I was told to shuffle my feet in an attempt to avoid stepping on one. They can do massive damage to human feet, and are a sure way to ruin a fishing trip.

And that is just the beginning of the adventure that can found in the jungles of Bolivia. We had some incredible fishing while we were there, but I’d be lying if I said that the fishing was the highlight of my trip. I was in a part of the world that’s relatively untouched by man — a world away from the perceived safety and comfort of civilisation… and it felt so damn good to be that vulnerable and alive.