It’s hardly necessary to explain the appeal of fire; as a species, our appreciation for controlled flames is so acute that we instinctively turn toward a campfire even when we’re already warm and well fed. When times get hard in the woods or mountains–when you’re cold, hungry, lost, or scared–your desire for fire can become almost unbearable.

Learn the basic principles of fire-making and you’ll enjoy your time in the backcountry all the better. Even when you don’t need a fire, it’s comforting just knowing that you could make one if you wanted it.

It’s wise to pack along fire-starting materials when hunting in wet country, and to pick up suitable fire-starting materials as you encounter them rather than waiting until you desperately need them.

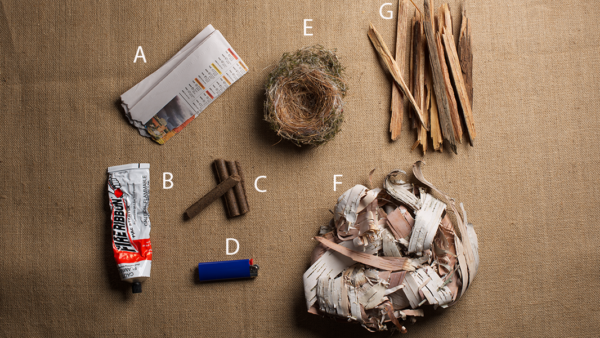

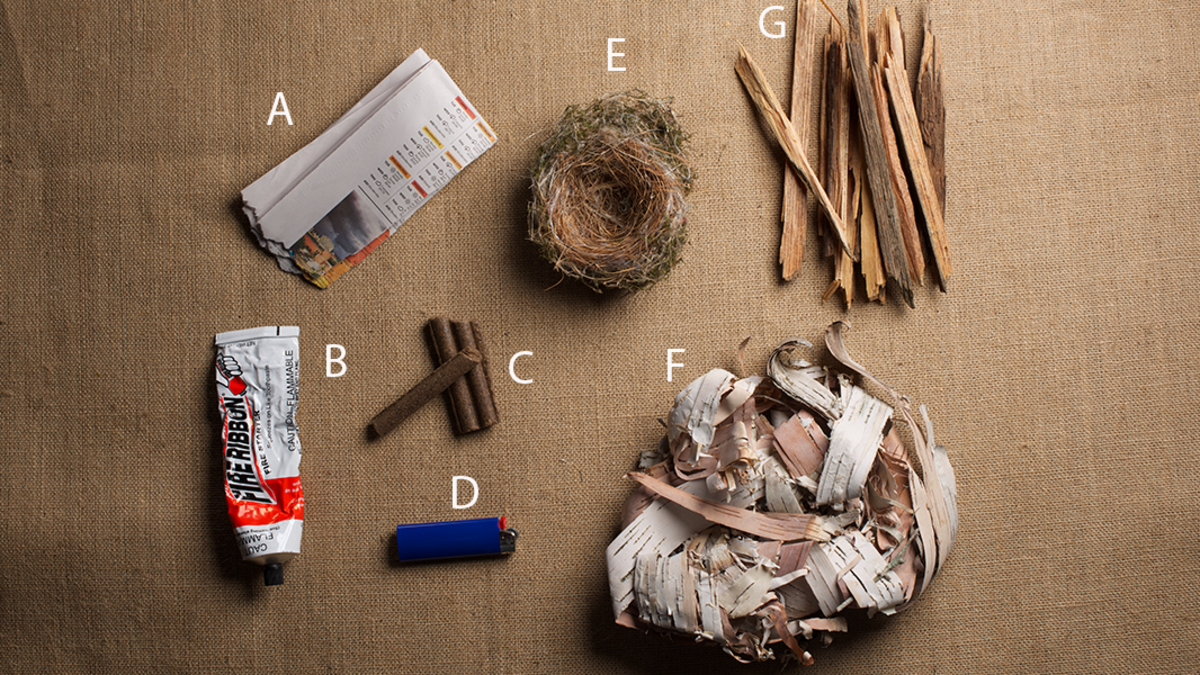

A: A few strips of newsprint tucked inside a Ziplock can be a lifesaver.

B: Commercial fire-starting pastes, such as Mautz Fire Ribbon, are cheap simple products that take much of the stress out of fire building. A proper, well-organized pile of tinder and kindling on top of a quarter-sized dab of paste will rarely refuse to burn. Or, if necessary, you can skip the tinder altogether and jump right to pencil-sized sticks.

C: Coughlan Fire Sticks are waterproof, non-toxic, and let off a strong and long-burning flame.

D: Keep two lighters in your gear and keep at least one of them in a sealable plastic bag. It doesn’t hurt to be over-prepared, carry a few wooden matches inside a waterproof match-holder as well.

E: Dried bird’s nests are excellent emergency fire starters. In rainy conditions, check tree cavities for bird’s nests; often, these are perfectly dry when everything else is dripping wet.

F: The bark from paper birch burns amazingly well. It is full of resinous oils that repel water and ignite into a hot blaze when touched with a match or lighter. It is easy to collect; sheets will literally fall away from living trees.

G: Fatwood, or heart pine, is a highly combustible kindling taken from the resin-impregnated heartwood of pines such as jack pine and longleaf pine.