My reaction to the news was visceral. I stared at my hands, remembering that 10 days earlier I hadn’t worn plastic sleeves or rubber gloves when field dressing a buck. That deer, as it turned out, had tested positive for chronic wasting disease.

It wasn’t out of ignorance. I know better than that. I’ve always followed the Wisconsin DNR’s guidelines for field dressing deer and it’d been part of my harvest routine since the disease was discovered here in 2002. My glove supply was empty and the guts needed to go, though, so I haphazardly rolled up my sleeves and worked with my bare hands.

Now I had likely exposed myself to CWD-positive prions. Over the span of 15 years, the disease had made it to Westford Township, to the Duren Farm, to meat in my very own hands.

In areas like ours, it’s understandable why folks like me would be concerned about CWD and it’s proven and possible effects. But for sportsmen who live or hunt in areas where CWD has yet to be discovered, there’s less urgency. Why should those hunters, conservationists and citizens care about the disease, though?

The answer is simple: If you don’t have it, you don’t want it. Regardless of the presence or prevalence of CWD in your area, everyone should get behind efforts to control the spread of this disease.

Is CWD a Human Health Issue?

There is currently no evidence that CWD has spread to humans. But, I think my immediate concern to the news of having handled a CWD-positive deer was warranted.

The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control have been clear on that: “To date, there is no strong evidence for the occurrence of CWD in people, and it is not known if people can get infected with CWD prions.”

They do recommend, however, that because of mixed results and ongoing research, that it’s important to prevent human exposure to CWD.

I accept that I was exposed to CWD when I field dressed that buck, and possibly have been in other instances. I’m not losing any sleep over it. Like any risk we learn about in life, we should follow science-based, common sense recommendations and continue to do what we can to minimize our risk of exposure.

Whether or not CWD will ever become a human health issue is an open question. There are many examples of zoonotic diseases (animal diseases that can infect people, and vice versa) and scientists really cannot predict whether CWD will become a human health issue. That alone should give us all reason to care about CWD.

Does CWD Affect the Resource?

The most immediate reason for anyone to care about CWD is its effect on individual cervids, and the effect on herds as a whole.

CWD is hard on individual cervids. Once a whitetail, muley, elk, caribou or moose contracts CWD, they will die from the disease or complications from it in as little as 17 months. As the disease destroys the brain, the last few weeks of a CWD positive animal’s life are gut wrenching to think about.

It becomes confused, lethargic, wanders in circles, becomes unstable, drools and wastes away. The animal is much more susceptible to predators and other dangers as brain function and its survival skills weaken. Eventually it dies from a number of possible health complications brought on by CWD, or the disease itself. If you care about animal welfare, you should care about CWD.

CWD is also hard on the deer herd. It changes the dynamics, structure and population of a herd. Although I mostly concern myself with whitetails, research has shown population level impacts on mule deer herds in the West.

As one project from Wyoming concluded, “With this study, we have demonstrated the long-term consequences of endemic CWD on a free-ranging mule deer population. Chronic wasting disease caused significant declines in the study mule deer herd as well as in sympatric white-tailed deer.”

Just that line should give anyone interested in mule deer or mule deer hunting plenty of reason to care about CWD.

Whitetail deer are the most sought-after game species in the country. Southwest Wisconsin, where the biggest incidence of CWD is located, is home to an enormous population of whitetail deer. Even with prevalence of CWD as high as 25% in one county, there is no shortage of deer. But CWD changes what that deer herd looks like.

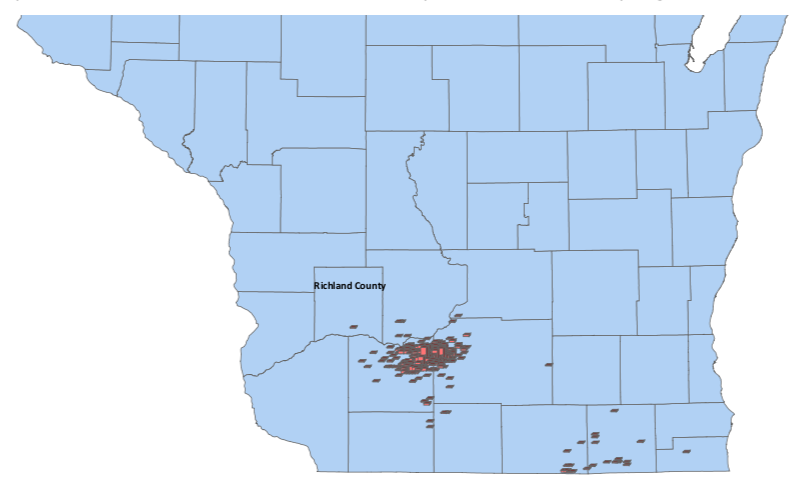

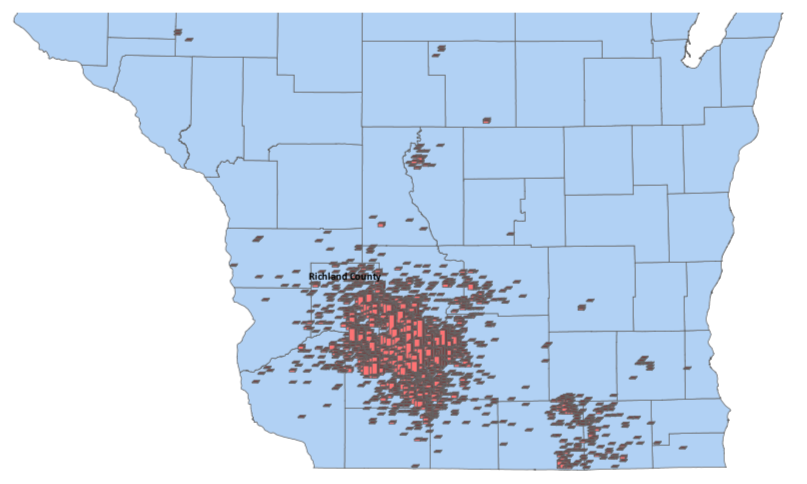

Mike Purnell is a landowner in southeastern Richland County, about 20 miles north of the area where CWD was first discovered in Wisconsin, and about 20 miles south of the Duren farm. Purnell and his group began purchasing land in 1987 for hunting. They began testing deer in 2004 and got their first positive case in 2009. (Every CWD-impacted state has its own system for testing hunter-killed deer for the disease. Contact your local DNR to find out more). In Purnell’s case, the disease had spread over 20 miles in just 7 years, and covered most of that ground after aggressive management strategies were abandoned.

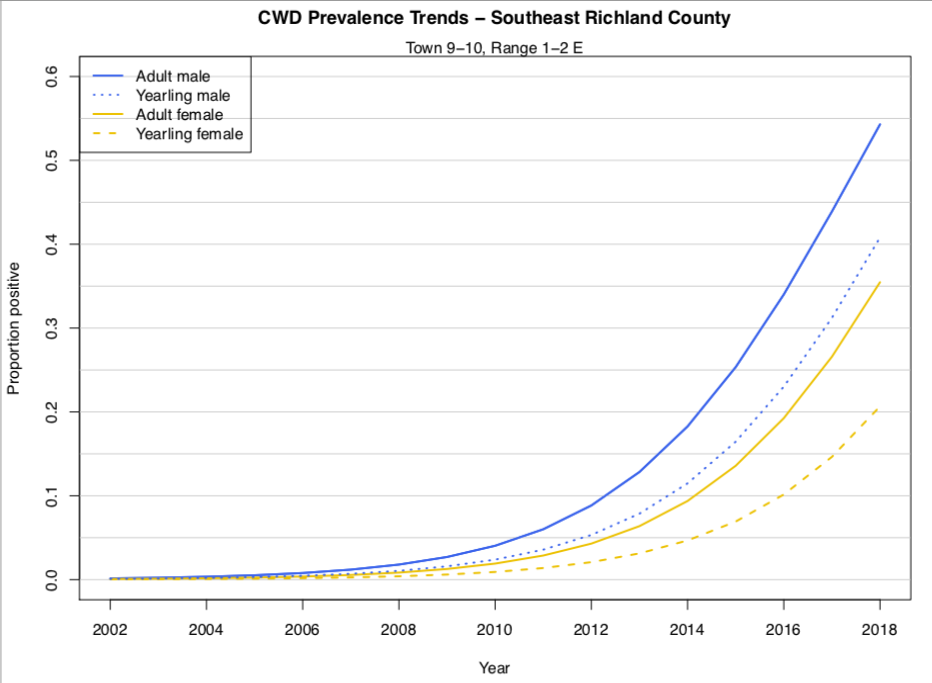

Although anecdotal, in the last 10 years Purnell’s group has seen a rapid increase in the number of positive deer taken on their property, which mirrors the DNR prevalence estimates for that area. The graph shows prevalence growth over time, and is currently at over 55% in adult bucks, 40% in yearling bucks, 35% in adult does and 20% in yearling does. In the past 16 years, prevalence grew slowly but then came a tipping point. In the last 7 years, prevalence took an almost vertical track. Even more startling and concerning is that both sexes and all age classes are on the same trajectory.

In 2017, Purnell said 24 of 43 deer they killed tested positive for CWD. All the antlered bucks, about half the does and “a couple” fawns tested positive. In 2018, of the 24 deer tested for CWD, 12 were positive, including seven bucks and five does.

Until a few years ago, Purnell’s party managed the property for older bucks and a balanced, lower population herd. “We don’t have any big, older bucks. CWD is killing them,” he said.

Although there are still plenty of deer in the area because of the outstanding habitat and food supply, the deer herd is trending younger. Older, mature deer are disappearing from the landscape. That dramatic change happened in about 10 years. Anyone interested in mature deer should care about CWD and what it does to herd structures.

CWD Funding

If you follow college athletics, you know that every university has a couple major programs that are the identity of a school’s athletic program. They are the highest profile, most popular sports that are the big money makers for the athletic program. Their ticket sales, merchandise sales, TV revenue and related events are the basis for the entire athletic department budget and help fund the smaller, less popular sports.

Big game species, especially those in the cervid family, are to state departments what those major sports teams are to athletic programs. If CWD threatens, changes, reduces or eliminates the deer and elk herds on a wide scale, how will natural resource agencies fund management of the “lesser” game species?

Billions of dollars for wildlife conservation are generated by deer and elk hunting. Millions of related jobs and industries will be affected.

CWD is one of the biggest conservation challenges of our lifetime. Conservation is thinking about what is best for the resource and looking to the future. Conservation is about realizing that it’s not ours, it’s just our turn.

Feature image via Captured Creative.