You recognize the names P.O. Ackley and Roy Weatherby, but what do you know about Charles Newton?

Not to be confused with Isaac Newton, Charles Newton was another inventor and engineer who some have called the “father of high-velocity rifle cartridges.” Newton designed several popular cartridges that are still commercially available (.250 Savage, .220 Swift, and .22 Savage), but he also pioneered his own high-speed rounds that failed to achieve commercial success. That, according to Frank C. Barnes in “Cartridges of the World,” wasn’t due to a lack of ballistic potential.

“Newton designed cartridges back around 1910 that, had modern powders been available, would have equaled the performance of present-day high-velocity developments of similar caliber and type,” Barnes notes. “The Newton designs must be recognized as too advanced for their day. If Charles Newton were alive and his cartridges introduced today, they would be hailed as brilliant and modern in every respect.”

I’d wager most rifle hunters haven’t heard of Charles Newton or the cartridges he invented, and that’s a shame. While direct lines of influence are hard to disentangle, his brain was working along the same wavelengths as 21st-century cartridge designers. He may be the most influential wildcatter you’ve never heard of, and his inventions are some of the best commercial failures in cartridge history.

.22 Newton

Take, for example, the .22 Newton. Newton had worked on the .22 Savage Hi-Power for the Model 99 lever-action rifle, but he didn’t believe that cartridge had enough juice to take down a deer. So, he took a .30-06 Springfield case, shortened it about 0.25 inches, and necked it down to accept a 0.228-inch-diameter bullet.

The result was an ultra-fast .22-caliber cartridge that could launch a 90-grain bullet 3,100 feet-per-second or a 70-grain bullet 3,250 fps. For context, a .223 Rem. can only achieve about 2,700 fps with a lighter 77-grain bullet, and while a .22-250 Rem. flies nearly 3,700 fps, it must use a bullet nearly half the weight (55 grains).

Much like today’s cartridge designers, Newton’s .22-caliber cartridge used heavy-for-caliber bullets loaded into a wide case with a relatively steep shoulder angle. In his book “Wildcat Cartridges,” Fred Zeglin lists the shoulder angle as 21 degrees, which is not as steep as, say, the 6.5 Creedmoor’s 30 degrees but definitely steeper than the .30-06’s 17.5 degrees. Big game hunters tended to prefer another of Newton’s offerings, the .256 Newton, but Barnes points out that subsequent .22 wildcatters were inspired by Newton’s design.

“Many later wildcatters have followed Newton’s lead — Ackley, Clark, Huntington, and Carmichael come to mind with their variations of a .22 on this same basic cartridge design,” he writes.

As with many of Newton’s cartridges, the .22 Newton wasn’t chambered in any production rifles other than the ones Newton produced at his own rifle factory. The .22 Newton was first offered in a Newton rifle in 1914 but wasn’t around very much longer. Whatever advantages the .22 Newton offered, they weren’t recognized by the general public at the time.

.256 Newton

Newton was leading the heavy-for-caliber bandwagon before it was cool, and we can say the same about 6.5mm cartridges. The .256 Newton was introduced by the Western Cartridge Co. in 1913, making it the first American-designed, commercially available 6.5mm cartridge in history. After Western stopped producing it in 1938, it wasn’t until two decades later that another company began offering a 6.5mm rifle cartridge (the .264 Win. Mag.).

Like the .22 Newton, the .256 Newton used a necked-down .30-06 case. Barnes records that it could fire a 120-grain bullet 2,980 fps and a 140-grain bullet 2,890 fps. By contrast, a 6.5 Creedmoor shoots a 120-grain pill 2,900 fps and a 140-grain projectile 2,700 fps, depending on the particular loading.

Newton’s sales pitch for the .256 should sound familiar to anyone who’s investigated the Creed and other modern cartridges. According to Zeglin, Newton claimed that the 256 had 23% more energy at 300 yards than the 30-06. Since the Springfield was considered the most powerful American cartridge for big game, “Newton enthusiastically touted his 256 as ‘adequate for the largest of North American Big Game.’”

Newton’s cartridge probably couldn’t match the Creedmoor’s accuracy, and its long-action case obviously didn’t use powder as efficiently as the short-action Creedmoor. But remember, Newton wasn’t working with modern powders. Barnes points out that with today’s slow-burning powders, the .256 Newton’s performance can be improved over factory ballistics. Plus, its use of the .30-06 case allows handloaders to create their own cases out of the readily available Springfield, making the Newton a kind of lovechild between old-timers and 6.5mm fanboys.

.30 Newton

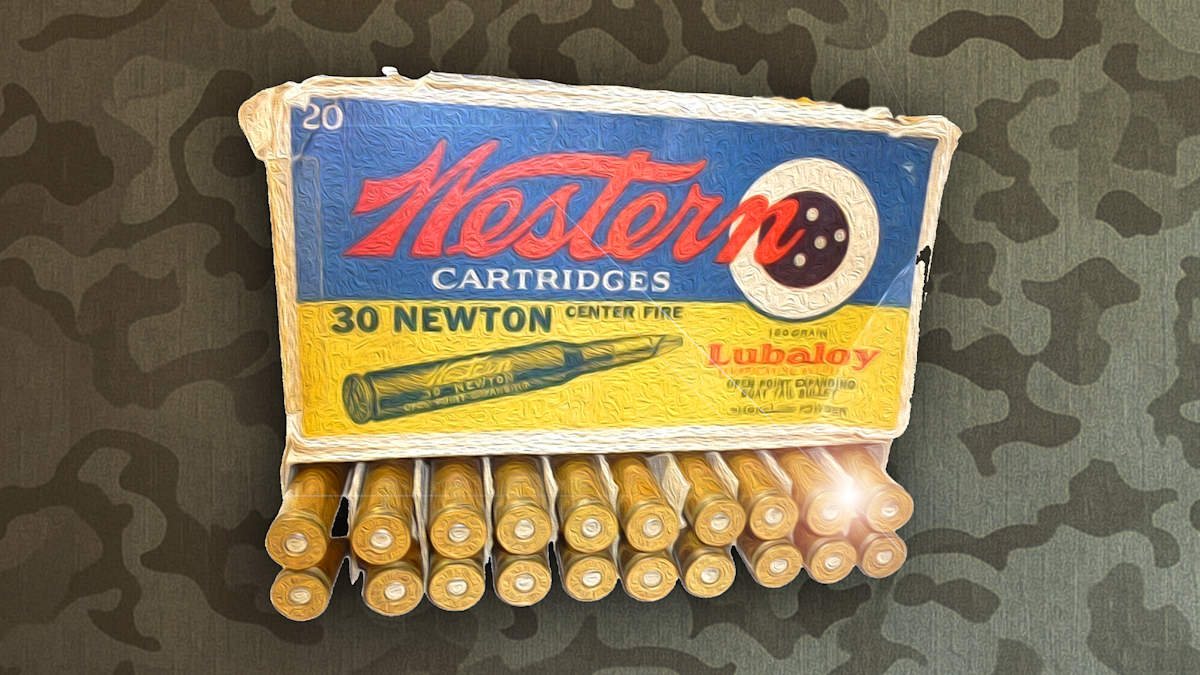

Newton’s most enduring creation is likely the .30 Newton. You can still find rifles chambered in this caliber on websites like GunBroker, and the cartridge inspires the occasional think piece like the one you’re currently enjoying.

Newton designed the cartridge for then-well-known German gun maker Fred Adloph, which resulted in the unfortunate appellation, the “Adolph Express” (this was in 1913, remember). A few years later, according to Barnes, the Western Cartridge Co. began producing factory loads, and Newton matched those with rifles from his own factory.

Ballistically, the .30 Newton is remarkably similar to the .300 Win. Mag. It used bullets in the 150- to 200-grain range. It could launch the lighter bullets about 3,100 fps, and the heavier bullets left the barrel closer to 2,700 fps. Like the .300 Win. Mag., the sweet spot was 180-grain bullets, which flew between 2,800 and 2,900 fps at the muzzle.

The .300 Win. Mag. has been one of the most popular cartridges ever made since it was released in 1963. But for whatever reason, the hunting public and the commercial firearm industry at large weren’t ready for the .30 Newton in 1913. In a prescient move, Newton decided to change the name of the cartridge to the “.30 Newton,” but it didn’t help the bottom line. He stopped making rifles in .30 Newton in 1920, and the Western Cartridge Co. stopped producing the cartridge in 1938. For handloaders and wildcatters, brass can be formed from RWS 8x68mm cases, but those are more difficult to come by than the .30-06 cases used by the .22 and .256 Newton.

Last Shot

These aren’t the only cartridges Newton developed, but they are some of the most forward-thinking. A .22 that uses heavy-for-caliber bullets, an American-made 6.5mm, and a 30-caliber magnum are all concepts that have become staples of the modern firearm landscape. Maybe we would have gotten here without Newton’s genius… but maybe not. It’s tough to say, but if high-speed hunting rounds have helped you put meat on the table, you owe at least a little gratitude to the OG of speed, Charles Newton.

If you want to learn more about Newton and his cartridges, check out Chapter 19 of Fred Zeglin’s book, “Wildcat Cartridges.”