In the years between WWI and WWII, the American public was enamored with sensationalized news about a vicious new breed of criminal. Unlike bandits of the Old West riding on horseback and armed with six-shooters and lever guns, these Great Depression-era outlaws rode around in powerful V-8 Fords armed with machine guns and .45 automatics.

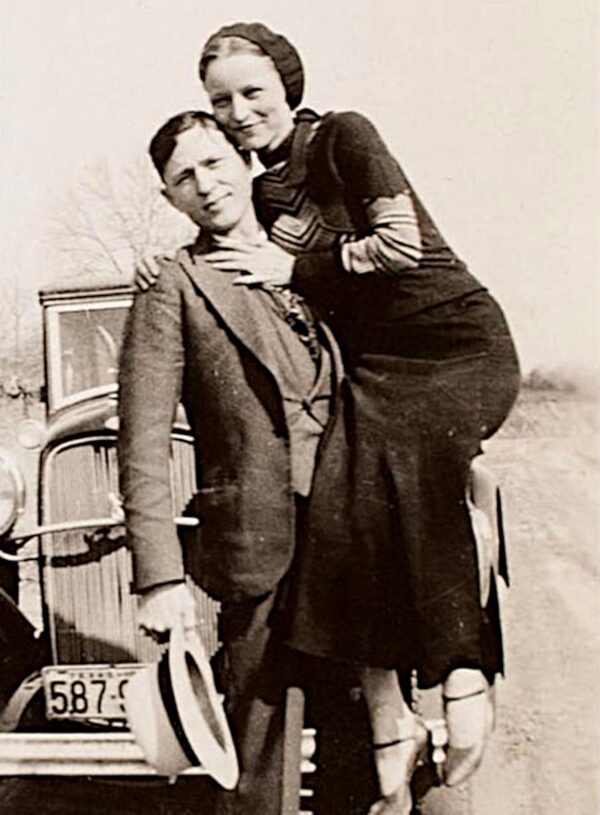

While John Dillinger is often considered the most famous of the “public enemy era” criminals, a couple of young terrors from Texas captured the nation’s imagination like none other. In addition to a laundry list of practically unbelievable criminal escapades and a seemingly preternatural ability to avoid capture, they also had love on their side—and fans as fervent as rock-star groupies.

The American Couple of Crime

Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were born in Texas, a year apart. They grew up in a nation of failed banks, failed farms, lost hope, and dust.

Parker dropped out of school at 15 and married fellow dropout Roy Thorton in 1926. They split in 1929 after a rocky relationship, but were never legally divorced. By 1930, she was an anonymous waitress living in Dallas.

Crime’s most famous couple most likely met by chance in January 1930, crossing paths at Clyde’s buddy’s house in Dallas. Clyde was 20, Bonnie was 19, and they both were smitten with each other.

Their budding romance was interrupted when Clyde again went to prison for car theft. He soon escaped using a weapon Bonnie smuggled to him, but was quickly recaptured. During this stint in prison, a fellow inmate sexually assaulted Clyde, and he responded by crushing his skull with a pipe. No time was added to his sentence because another inmate, who was already serving life, took the rap. Clyde was later paroled in 1932 thanks to a petition filed by his mother. By all accounts, his time in prison changed him greatly.

The Spree

Bonnie and Clyde’s crime spree began as soon as Clyde was a free man. They assembled a small gang, known simply as The Barrow Gang, and eventually embarked on a series of daring bank robberies. They traveled the Midwest, knocking over rural stores and gas stations from Minnesota to Texas along the way.

The gang members included Clyde’s brother, Buck Barrow and his wife Blanche, W.D. Jones, Henry Methvin, Raymond Hamilton, Joe Palmer, and Ralph Fults. But it was Bonnie and Clyde who got all the headlines and became icons of Depression-era crime.

The Barrow Gang killed nine police officers, four civilians, and robbed 10 banks before the murderous couple met former Texas Ranger Frank Hamer in Louisiana. Their crime spree ended in a hail of police gunfire on May 23, 1934.

The Importance of Firepower

The gang stayed ahead of law enforcement for as long as they did by moving quickly and being armed to the teeth.

They chose cars with powerful engines that could cover a lot of ground. This made them extra evasive during a time when there was little communication or cooperation among different law enforcement agencies, especially across state lines. When they did face off against police, the gang came out on top thanks to gun superiority.

Cops armed with service revolvers and pump guns were met by full-auto .30-06 fire from M1918 BARs, semiautomatic shotgun blasts, and .45 ACP rounds from semi-auto M1911 handguns.

While the .30-06 rounds shredded anything police could use for cover, the steel bodies of the V-8 Fords that Clyde preferred deflected handgun bullets and .45 ACP slugs from Thompson machine guns.

The Barrow Gang, always outnumbered, successfully engaged in five major shootouts with police. They traveled with an arsenal of powerful firearms, many of which were lifted from National Guard armories and customized. At the time of their death, Bonnie and Clyde had the following guns in their car:

- (3) full-auto Browning Automatic Rifles (BAR) in .30-06

- (1) 20-gauge Remington Model 11 Semi-Auto sawed-off shotgun

- (1) 10-gauge Winchester Model 1901 lever-action, sawed-off shotgun

- (1) .32-caliber M1903 Colt automatic pistol

- (1) .38 Colt Detective Special revolver

- (1) .25 ACP Colt automatic pistol

- (1) .45-caliber Colt M1909 revolver

- (7) .45 ACP Colt M1911 automatic pistols

They also had 100 loaded 20-round BAR magazines, some in bandoliers, and 3,000 rounds of other assorted ammunition.

From the modifications they made, we can tell the couple carefully considered the tactical advantages of their tweaks.

“The gun from Bonnie and Clyde’s rolling arsenal that gets the least attention is their cut-down 10-gauge Winchester 1901 lever-action shotgun,” said firearm historian T. Logan Metesh of High Caliber History.

“Anyone who has shot a 10-gauge shotgun will tell you that it’s an experience in and of itself. Cutting down the gun’s barrel made it more maneuverable, but the buttstock was not chopped like the Remington Model 11 shotguns the gang used. This shows that they wanted the power of the 10-gauge, but recognized that also cutting off the buttstock would make it downright unmanageable, so they compromised by just chopping the barrel.”

Clyde’s Cut-Down Rifle

Clyde’s go-to firearm was a modified M1918 BAR. In 1932, a fellow criminal gave Clyde two BARs stolen from a Missouri National Guard armory. He instantly saw the advantages of the automatic rifle’s powerful cartridge, high rate of fire, and the ability to reload quickly with spare magazines. This kind of firepower was way beyond what local and state police, or even the FBI, had at the time.

A year later, the gang conducted two National Guard armory robberies, one in Oklahoma and another in Illinois, scoring several BARs, M1911 pistols, Model 11 shotguns, and a bunch of M1917 revolvers. Plus, they scored a whole lot of ammo and magazines.

When Clyde talked about his “scattergun,” he was referring to the BAR, not a shotgun, because when he started shooting, everyone scattered. He shortened the barrel and gas tube on his BARs and preferred custom magazines made from two BAR mag bodies welded together with a 40-round capacity.

The resulting firearm was similar to a variant of the BAR produced after WWI, the Colt Monitor. It was an M1918 with a shortened barrel and gas tube, no bipod, a pistol grip, and a Cutts Compensator on the muzzle. About 130 were produced, and all were sold to law enforcement entities.

Dallas County Deputy Sheriff Ted Hinton was armed with a Colt Monitor when he helped ambush Bonnie and Clyde in 1934. He was on Frank Hamer’s team because he could identify the outlaw couple by sight. He knew Bonnie from when she worked as a waitress in Dallas and he had grown up with the Barrow brothers. He even worked with Clyde for a stint at Western Union.

The Monitor Hinton used was on loan from the Texas National Guard. He previously survived a shootout with the gang in Sowers, Texas, where he learned that there was no such thing as too much firepower when it came to Bonnie and Clyde.

Bonnie’s Sawed-Off Shotgun

The gun most associated with Bonnie is the cut-down, semi-auto Remington Model 11 shotgun she is seen holding in photographs. The sawed-off Model 11 was a gang favorite, but Bonnie’s personal shotgun was chambered in 20-gauge with a barrel that ended just in front of the magazine tube and a stock abbreviated a couple inches behind the grip. She had this shotgun with her when she was killed.

Remington produced a riot gun version of the Model 11 with a 20-inch barrel, which the U.S. Army purchased in large numbers. That’s why the gang was able to swipe them during their National Guard robberies.

When the situation called for it, Clyde also liked to use the shotgun. Bonnie reportedly created a special pair of trousers for him with a hidden, tear-away zipper running down one pantleg. This allowed him to keep the Model 11 next to his leg, holding the pistol grip through a hole in the pocket. He could then raise the gun and fire from the hip in one swift motion before anyone even knew he was holding a shotgun. The baggy pants were in style, yet practical.

The Guns that Killed Bonnie and Clyde

Bonnie and Clyde’s story ended as violently as they lived—perhaps more so. Six well-armed men, including Frank Hamer, ambushed their car on Highway 154 between Gibsland and Sailes in Louisiana.

Hamer was carrying a semi-auto Remington Model 8 rifle. He fired the first shot, which went through the windshield of the couple’s car and hit Clyde in the head. The posse opened up with various rifles, including Hinton’s Colt Monitor. When the rifles were empty, they picked up loaded shotguns. When those ran dry, they shot their pistols until the car rolled into a ditch.

The vehicle was swiss-cheesed with bullet holes. The bodies of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, dead on the bench seat of their stolen Ford, had been hit 43 times. Bonnie was 23. Clyde was 24.