It’s late March in Montana and snow is coming down hard outside my living room window. The wind, blowing from right to left, is pounding the hell out of an already established snow drift that’s been developing since November. My fireplace is going strong and I’m working on a freshly poured glass of straight bourbon whiskey that would normally round out a fine evening.

There’s beauty in a sipping whiskey, good fire, and no reason at all to worry about the outside world—it’s an opportunity I always try to savor.

This time, I just can’t seem to manage any enjoyment, but I’m not to blame. It’s Col. Tom Kelly’s fault.

I’ve just finished my ceremonial, if not essential, pre-turkey season reading of his book The Tenth Legion. My mind is flush with visions of spring and all that comes with it.

It’s as if there’s a projector in my head playing a loop of all the moments that define my favorite time of year. I can see it all: steam rolling from the beak of a fired-up tom, the silhouette of a gnarly old cottonwood tree full of roosted birds, and the frantic spitting and drumming of a strutter.

Even though this has become a fundamental torture around my house, I’m thankful for the connection that Col. Kelly has provided with his seminal work. Every year when I can’t stand it anymore, I crack open its pages and rediscover a world that seems so foreign during the winter months. I time travel.

For me, The Tenth Legion is less of a book and more of a rite of passage. The words can stoke the soul of a turkey hunter. They also have the unique ability to describe the depth of it.

“Many people who hunt turkeys do so with an attention to detail,” Col. Kelly wrote, “a regard for strategy, tactics, and operations, and a disregard for personal comfort and convenience that ranks second only to war. As for all cultists, it never occurs to them that they may be anachronisms. Supremely unconscious of the rest of the world, blind and deaf to logic and reason, they walk along their different roads in step to the music of their different drums.”

Not only does Col. Kelly’s book accurately describe the “cult” of turkey hunters, it also provides amazing color to the wild turkey itself.

The book’s opening pages describe this bird as a worthy, yet mysterious foe whose legend is intertwined with the hunters who pursue him.

“Such is the depth of this mystique, and so thick is the veil before the truth” Col. Kelly wrote, “that before the creature can even be approached with a modicum of reason and logic, it becomes necessary to peel away the layers of the legend—much as one peels the skin from around an onion.”

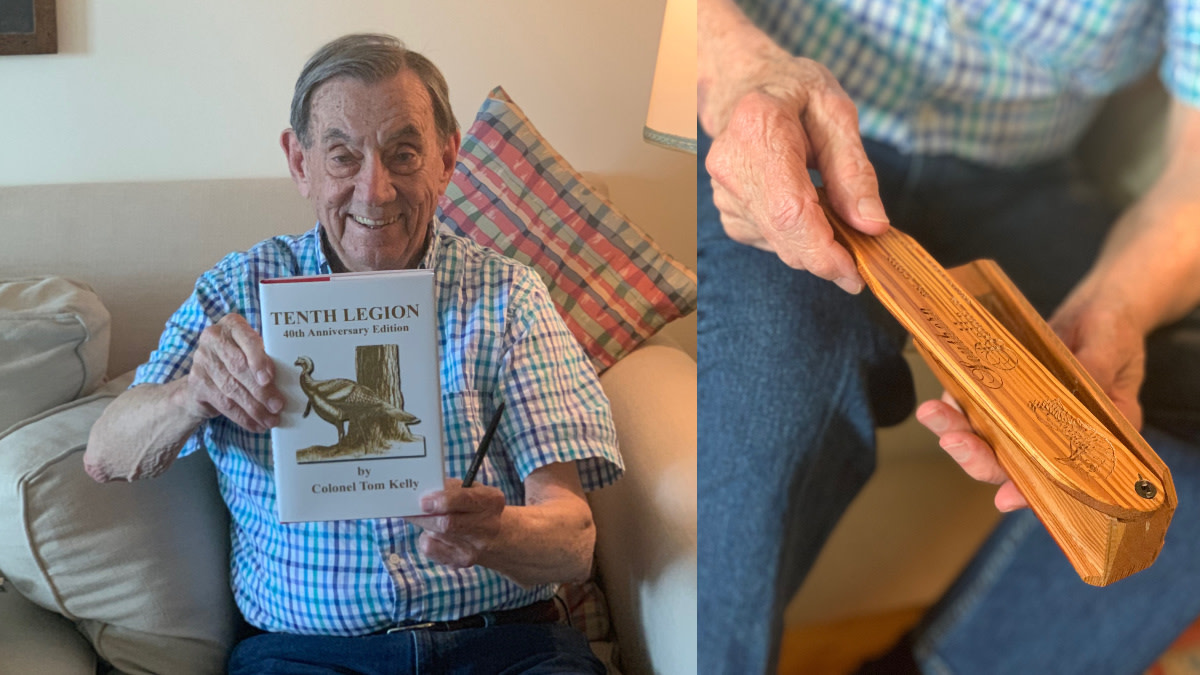

The man that penned these words was not always a writer, but he was from a young age a turkey hunter. Col. Kelly was born in 1927 in Mobile, Alabama, a typical southern kid. He loved to go outside and explore; he played the banjo.

When he was 11, the future Colonel—he earned the title of bird colonel after serving two tours in the U.S. Army—went turkey hunting for the first time with his uncle. It was a pretty crazy idea back then. There just wasn’t that many turkeys around and there were even fewer folks that actually hunted them. That didn’t matter to Kelly, he fell into the pursuit and never looked back.

It took him almost 40 years of turkey hunting to finally decide to write The Tenth Legion. His wife encouraged him to write down the many stories that were so popular around the dinner table and in hunting camp.

In 1973, the first edition of the book was born. Col. Kelly didn’t think the thing would sell more than a hundred copies and expected that it’d be a nice Christmas gift for friends and family. In fact, he only had 555 printed on the first run.

Yet, very quickly, it was something much more.

The book became a local, then regional hit, and persisted in its popularity for the next 40-plus years. Today, Col. Kelly’s original writing desk is enshrined in the National Wild Turkey Museum at the headquarters of the NWTF.

He has become the poet laureate of turkey hunting.

To read Col. Kelly’s description of a morning in the turkey woods is to understand why our hunting memories are so flawed. Time seems to simultaneously fool us into arrogance and force us into appreciation. How else would the feeling of excitement before the first morning of turkey season be accompanied by the idea that it’s going to play out just as you’re expecting?

The ponderance of nature and the minutiae—a pure hatred of sticker bushes and the insanity of waking up at 3 a.m. among them—are laid bare in The Tenth Legion. So are the people that the Colonel calls legionnaires.

I am one of the many who are a part of the cult-like following constructed around this book—much like the connection of Robert Ruark to Africa, Nash Buckingham to waterfowl, or Hunter S. Thompson to cocaine.

Quite simply, it’s the best turkey hunting book of all time. I’ll read it every year and revel in what Col. Kelly calls a “deviant subculture,” of which I’m proud to be a member.