From 1938 to 1962, trucks regularly drove nonstop from central Wisconsin to the Deep South with cargos of whitetail deer for rebuilding wild herds from Florida to Louisiana.

Many of those deer were released from their plywood box-traps into central and south-central Georgia during the 1950s and early 1960s. The trip from their home woods at the Sandhill Game Farm near Babcock, Wis. covered nearly 1,050 miles. Wallace Grange, Wisconsin’s first game management superintendent, owned that 9,150-acre game farm. The site, now the Sandhill Wildlife Area, has been a research facility since Grange sold it to Wisconsin in 1962.

Grange was considered a competent biologist when he left government work in 1932. After moving to his Sandhill property, he enclosed it with a 9-foot-tall deer-proof fence. He helped fund his game farm by selling field-dressed deer to New York City restaurants for 75 cents a pound. He also sold live fawns for $50 and adult deer for $125 to Southern states for their restocking efforts.

Unwittingly, Grange likely contributed to the nation’s sad legacy of interstate wildlife disease transmissions. Roughly 60 years after Grange’s deer arrived in Georgia, researchers identified them as the most likely source of “cranial abscessation syndrome” in the Peach State’s whitetails.

Bone-Eating Disease

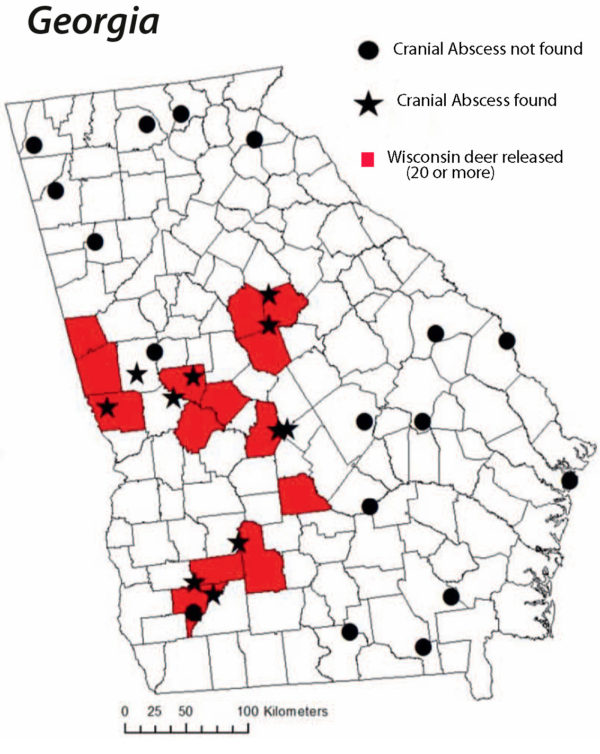

This bacterial disease sometimes eats through a deer’s skull, usually through a buck’s antler base—the pedicle—and kills the deer if the abscess infects its brain. While studying CAS in recent years, University of Georgia researchers found no historical record of it in the state. The scientists made the Wisconsin link by studying release sites for Georgia’s restocking program. Nine of 11 sites with CAS were in counties in which over 20 deer came from the Sandhill Game Farm. Two other CAS sites were in counties neighboring areas restocked with Sandhill deer.

Given the passage of time, the UGA researchers can’t prove that connection scientifically, and therefore must label it “anecdotal evidence.” Still, they think CAS likely reached Georgia by truck from Wisconsin, purely by accident and with the best possible intentions. After all, the South’s deer herds had been decimated by habitat loss and unregulated hunting by the early 1900s, and state wildlife agencies across the Eastern U.S. helped however they could.

Unlike Georgia, CAS has long been documented in Wisconsin, where biologists consider it “ubiquitous,” meaning it’s found statewide. The disease rarely kills female deer, but studies suggest CAS can cause from 6 percent to 35 percent of natural deaths in bucks.

Even so, confirmed deaths by CAS are uncommon. Of 1,232 sick deer reports called in by Wisconsinites to the Department of Natural Resources from 2012 through 2018, only 20 (1.6 percent) were confirmed to be CAS. For comparison, the Wisconsin DNR confirmed chronic wasting disease in 1,054 of 17,055 hunter-killed deer tested in 2018, a 6.2 percent infection rate. Ongoing research in southwestern Wisconsin also finds deer with CWD are twice as likely to die within the year than are healthy deer in the study area.

And although CAS has no scientific connection to CWD—a far deadlier illness with population-level impacts—folks often confuse the two ailments with each other. After all, deer suffering from either disease often stumble, look dazed, and lose their fear of humans. But bucks stricken with CAS typically look well-fed, even though they appear blind, with pus oozing from their eye sockets or antler bases. In contrast, deer reaching CWD’s “clinical” stage look emaciated as death nears.

Trucking Prions and Bacteria

Both diseases have also been spread far by truck. Twenty years ago, biologists considered CWD a “Western” disease. But after CWD was identified in Wisconsin and Illinois in 2002, researchers studying its distribution and prevalence concluded it likely crossed the Mississippi River 15 to 20 years earlier. Still, scientists will never know if CWD reached the East in live elk or deer sold to game farms, or in carcasses of hunter-killed elk or deer brought home from Colorado or Wyoming.

Either way, CWD differs vastly from CAS, which is caused by a bacteria that needs a physical pathway to reach a deer’s brain and kill it. Meat from CAS-infected deer is considered safe to eat. Health officials advise not eating meat from the head area, but all other meat is safe if properly cooked to destroy bacteria.

CWD is triggered by prions—a corrupted protein that concentrates in the brain, lymph nodes and spinal column—and kills deer within two years by destroying their brain. Although it’s more commonly found in bucks, CWD afflicts both genders. And even though there’s no evidence of CWD infecting humans, and science continues to find evidence of a strong species barrier between humans and CWD, health organizations recommend not eating meat from deer testing positive for the disease.

Still, CAS traits noted by UGA researchers can resemble those of CWD, given that both occur increasingly often as bucks age. CAS’s fatal brain abscesses, however, are caused by bacteria entering wounds in antler velvet, or through a damaged pedicle after the buck sheds the antler.

Such entries can begin with a “dirty shed,” an antler that breaks off prematurely with blood and skull bone attached to its base. Gabe Karns, who conducted CAS research at UGA and Auburn University, said it’s also possible dirty sheds are caused by bacteria pitting, eroding and weakening bone around the antler’s base.

Bucks often survive dirty sheds and superficial CAS infections, and then grow a spike antler on the damaged pedicle the next year. If the wound fully heals, the buck can grow normal antlers from that pedicle in subsequent years. But if the damage is deep and doesn’t heal, bacteria further deteriorates the skull and often penetrates along its suture lines. If the abscess reaches the brain, the buck almost certainly won’t recover.

Why CAS Infects Bucks

Bucks are most prone to CAS because they often suffer head cuts, scratches and other wounds while rubbing trees and sparring with rivals. The longer they live and the more aggressive they become, the greater their risk of CAS. “The more conflict, the more injuries, the more opportunities for infections,” Karns said.

When UGA’s researchers examined 5,659 hunter-killed deer at 28 sites around Georgia from 2011 through 2013, they found no CAS cases in 340 buck fawns and 2,106 females. Of 3,213 bucks 1.5 years and older examined, 80 (2.5 percent) had CAS. Another UGA study of 7,545 hunter-killed deer at 60 sites in Georgia found no CAS in buck fawns. However, the percentage of infected bucks was 1.7 percent for 1.5-year-olds, 1.8 percent for 2.5, 1.9 percent for 3.5, and 4.3 percent for 4.5 and older.

The researchers think CAS risks could further increase in well-managed deer herds with better-balanced sex ratios and age structures. Bucks in well-tuned herds increase in size, number and general nastiness. Bucks in herds skewing more female typically get shot as yearlings carrying their first forks or basket racks. They simply don’t live long enough to develop the risky, confrontational behaviors of older bucks.

That assumes, of course, that CAS is present. UGA’s 2011-2013 study of 28 sites around Georgia found no CAS cases in counties far from the historical release sites of Wisconsin deer. Likewise, the UGA researchers found no CAS in counties restocked with Texas deer. Texas has no history of CAS in its whitetails.

Where CAS is present, however, hunters, wildlife managers and groups like the Quality Deer Management Association work to limit its incidence. For instance, they oppose “antler traps” at winter feeding sites and adjoining trails. Tom Indrebo, a whitetail outfitter in Wisconsin’s Buffalo County, reports seeing old bed springs, big elastic bands and other contraptions above feed piles, placed there by shed collectors hoping to pull or knock antlers free for easier finding.

In his 2008 book Growing and Hunting Quality Bucks, Indrebo wrote: “I’m not impressed with some methods for literally snatching antlers from bucks’ heads. I can’t condone the risks of injuring these deer. Antlers fall off when they’re good and ready to fall off. If you break an antler off before its time, you risk injuring not only the buck’s pedicle, but the skull around and beneath it. (They can) develop pedicle infections that become fatal cranial abscesses. We shouldn’t subject deer to such long-term agony.”

Recognize the Risks

In similar fashion, UGA’s researchers warn wildlife managers and lawmakers to recognize the risks of moving disease and deadly pathogens when trucking wildlife. “You’re shipping the whole biological package, good and bad, anytime you move deer around,” Professor Karl Miller said. “You’re essentially moving an entire ecosystem with that deer.”

As UGA’s studies show, unintended consequences can hide for decades, and then unleash never-ending grief. Bradley Cohen, now a professor at Tennessee Tech University in Cookeville, summed up those fears when presenting CAS’s Wisconsin link at the 2014 Southeast Deer Study Group meeting in Athens, Georgia: “I have to wonder what type of legacy we’ll be creating if we don’t do something soon to end it.”

Feature image via Matt Hansen.