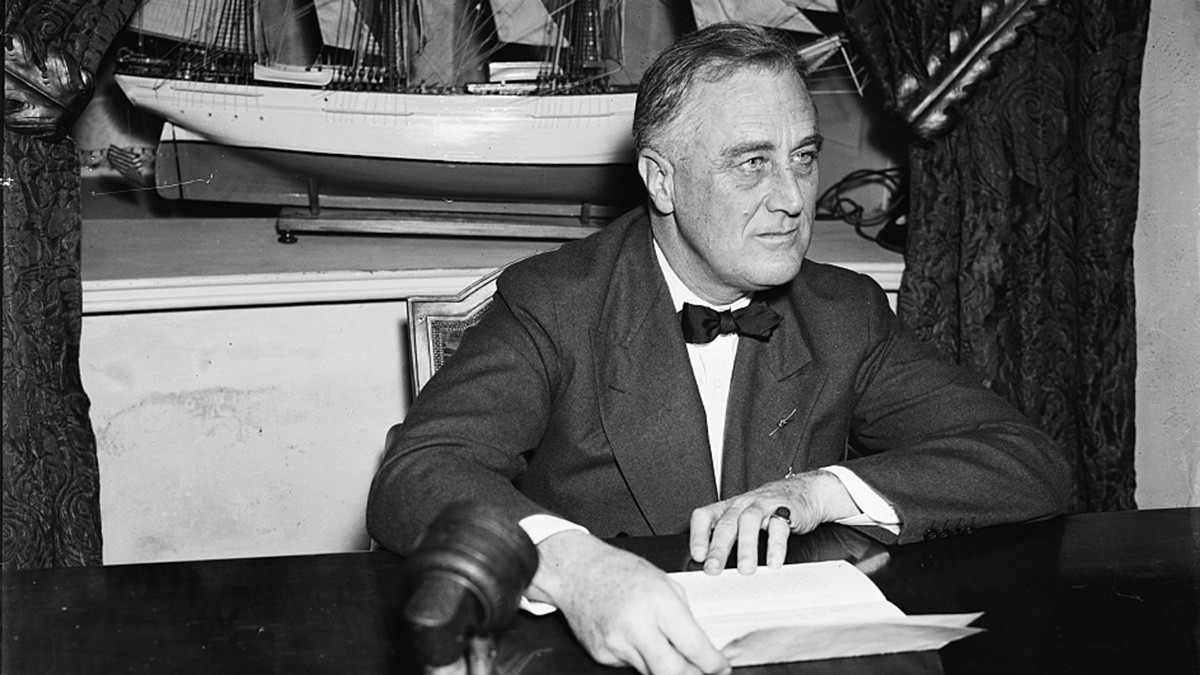

During the Great Depression, on February 3, 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called the very first North American Wildlife Conference, which gathered over 2,000 conservationists in Washington, D.C. It was a bold move for the President, and a turning point for who pays for what in the conservation world.

“My purpose is to bring together individuals, organizations, and agencies interested in the restoration and conservation of wildlife resources,” President Roosevelt said in his opening remarks. Speakers at the conference also came from Mexico and Canada, presenting a united front on the idea of conserving lands, waters and wildlife.

“Units in the federation will include such members as sportsmen’s clubs, nature leagues, conservation associations, farm groups, garden clubs and others interested in wildlife conservation and restoration,” F. A. Silcox, chief of the forest service, wrote in a press release.

President Roosevelt called for constructive proposals and concrete action, pushing his colleagues to do more than simply make speeches. After meeting for four days, the newly dubbed “wildlife conservation movement” outlined their goals. The second of which was to acquire for the purpose of conservation “adequate financial support from public funds.”

A year later, in 1937, President Roosevelt signed into law the “Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act” which amazingly went from introduction to signature in just 93 days. The monumental piece of legislation was dubbed the Pittman-Robertson Act after the lead sponsors of the bill, Sen. Key Pittman (NV) and Rep. Absalom Willis Robertson (VA).

The bill would set up a system in which the already existing 11 percent excise taxes on the sale of firearms and ammunition would be directed to the United States Fish & Wildlife Service to fund all the necessary programs designed to meet the goals of the new ideals of conservation. Among them were wildlife refuges, wildlife research, private and public habitat management and public access to land through land acquisition and easements. Decades later, hunter education and things like public target ranges became beneficiaries of the funds.

As time passed and the hunting and shooting sports evolved, several amendments were required to update the legislation, including an 11 percent tax on archery gear and a 10 percent tax on handguns and handgun ammo.

Pittman-Robertson was part of a sweeping reform that defined the era and remains a bedrock of the “user pays, public benefits” principle that has defined modern conservation.

What Does it Mean Today?

According to the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, in 2017 alone, state fish and wildlife agencies received over $629 million from Pittman-Robertson funds. The program has contributed over $11 billion since its inception.

The excise tax revenue from Pittman-Robertson obviously doesn’t come from sportsmen alone. There are millions of non-hunters that buy guns, ammo and archery equipment. Nonetheless, their taxes get thrown into the pot.

This is great news for wildlife. Even if there continues to be a precipitous fall in hunting participation as has been reported in recent years, those losses can be combated with more purchases at the gun counter. At least there are options to keep states well funded, and there is always hope that all Americans care about our wild animals and are willing at some level to pay up.

Nowadays, purchasers of guns, ammo, bows and arrows are not presented with the excise tax they pay on their receipts. The tax is paid for by the manufacturers directly to the federal government. Companies like Vista Outdoors, owners of brands like Savage, Federal Premium, CCI and more paid over $87 million to Pittman-Robertson funds in 2017.

Consumers are not informed of the excise tax in hunting regulation handbooks or the like. Chances are there is a large part of the hunting population paying for conservation that has no clue.

That brings us to the two questions every taxpayer asks at some point: Where is my money going and how does it get there?

To get some perspective on that it’s important to follow the money.

It’s essential to realize that the producer, manufacturer or importer pays the tax on the wholesale price of the products subject to program funding. Those companies or individuals provide the payment that is then collected by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau on firearms or the Internal Revenue Service on archery products. The funds are then deposited into the Wildlife Restoration Account, which is run by the USFWS. The USFWS places the tax revenue in what is called the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund and then distributes funds to the states via a special formula.

The formula basically has a system of filters and stipulations in order to determine how each dollar of the pot might be spent.

First, one-half of the excise tax on pistols is set aside to cover the costs of what is known as “basic hunter education,” which means safety programs and everything that it costs to have and maintain them. An additional $8 million goes to “enhanced hunter education,” which includes things like public target ranges.

Next, another $3 million is appropriated to projects that require cooperation between multiple states.

After a few other stipulations are considered, the remaining funds are divided in half based on overall land area and paid hunting licenses per state as compared to the number of hunters nationally.

Texas scores high in both these categories, so for example, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department takes the average of $16 million per year that comes from Pittman-Robertson funds and puts it back into conservation. This supports working with landowners to set and adhere to goals for habitat.

This all wraps up in one pretty fine package. The consumptive user pays a tax, the federal government collects that tax and then thoughtfully distributes that money back to the states. The states make sure that they have an educated group of hunters that have a place to hunt and animals to pursue.

Feature image via Library of Congress.