There’s a difference between book smart and bar smart. You may not be book smart, but this series can make you seem educated and interesting from a barstool. So, belly up, mix yourself a glass of LMNT Recharge, and take notes as we look at hidden treasures found right out your backdoor. Powered by LMNT.

In the latest episode of the MeatEater Podcast, we sat down with Benjamin Wallace of New York Magazine. Wallace recently wrote about the discovery of the Fenn Cache in Wyoming and how treasure hunters are keeping the chase alive. While most of Fenn fanatics have moved on with their lives, some continue searching for the treasure’s former location. Instead of looking for the ghost of the Fenn cache, I’d suggest they put that energy into finding these riches.

Lost Dutchman’s Gold Mine | Arizona

The legend of the Lost Dutchman’s Treasure is one of the most widely known—and widely disputed—caches in America. Although some versions of the tale tell of U.S. Army veterans or Apache Tribe members locating the mine, most credit Jacob Waltz with the discovery.

The story goes that Waltz helped rescue a family member of the Spanish Governor in New Mexico, who revealed to Waltz that there’s a lost mine filled with massive gold veins somewhere in the Superstition Mountains. Waltz found the mine, sold over $250,000 in gold to the U.S. Mint, then on his deathbed disclosed to someone the mine’s location. The result is a crudely-drawn map and sparse details that caused a 200-year hunt.

But, were it not for the death of Adolph Ruth, a treasure hunter in the 1930s, the Lost Dutchman’s Mine would never have made it into the national spotlight. According to reports, Ruth’s body was discovered in the Superstition Mountains with two bullet holes his the skull. Nearby was Ruth’s checkbook, which had a note saying he discovered the mine and gave detailed directions to find it. But to who? No one knows.

While thousands of treasure hunters still take to the Arizona desert to look for the mine every year, many historians believe this is an extreme and long-running case of “telephone” that led folks on a wild goose chase. This isn’t the only “Lost Dutchman Treasure” in the West.

Beale Ciphers | Virginia

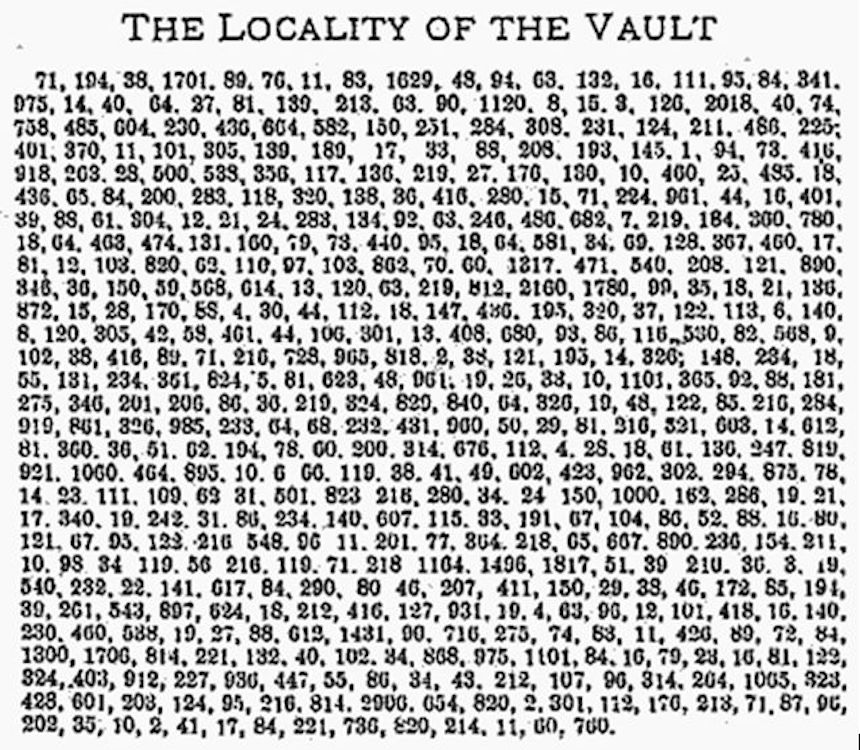

Thomas Beale was a 19th-century explorer who discovered gold, silver, and jewels while on a hunting trip near the Colorado-New Mexico border. He lugged the riches home to Virginia and then buried them. To ensure his treasure would be properly passed down, he created three cryptograms to reveal the treasure’s location, contents, and treasure finder’s next of kin.

To find the Fenn treasure you needed to decode a poem. It took someone 10 years to solve it. But to find the Beale treasure you need to decode three ciphers, and two of three are still unsolved after 200 years.

Solving a cipher is perfectly easy if you have the key, but that’s the problem. The key was either never created or lost along the way (the cipher texts changed hands many times before becoming publicly available in 1885). The second cipher, which is just a series of numbers like the other two, was decoded in the late 1800s when someone discovered the key was the Declaration of Independence. The opening sentence reveals that the treasure is hidden 4 miles from Buford, Virginia, but those are the only details available on the location. Based on what Beale says is in the chests, experts believe the treasure is worth more than $60 million.

Want to take a stab at the solve yourself? You can view the ciphers here.

The Fabergé Eggs | Unknown

In 1885, Czar Alexander III of Russia started an Easter gift-giving tradition with his wife. Each year, he would commission a special “Easter egg” to be made by a master goldsmith. Each egg was built with gold, silver, diamonds, rubies, and other valuable materials and contained some sort of surprise when opened. They each took more than a year to create.

The czar was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in 1916 and they confiscated every Easter egg from the ruler and his jewelry maker—50 total. The eggs slowly dispersed across the globe for the next century, with many ending up in the hands of museums and private collectors. Eight, however, are currently missing.

The most recent discovery of an Alexander egg was in 2015. It came to light when a man purchased the Third Imperial Egg from an antique store in the Midwest. He had no idea what it was, but thought the $13,000 price tag would allow him to make a $1,000 profit if he scrapped it for metal. But the man failed miserably.

According to the thrifter, he overvalued the amount of gold in the egg and couldn’t find a smelter willing to pay him enough to break even. In a last ditch effort to recover his investment, he Googled “gold egg” and realized what he had—a $33 million ornament that’s considered one of the most valuable works of art in the world.

It’s unknown where the final eight eggs are, but most believe they’re hiding in plain sight in the U.S. Ten of the eggs were brought here by Armand Hammer in 1931, and they make up the majority of the lost pieces. It’s a bit of an unconventional treasure hunt, but keep your eyes peeled for a gaudy egg in your grandma’s china cabinet or on a dusty thrift store shelf.

The James Gang Loot | Oklahoma

In 1876, the Jesse James Gang robbed a Mexican gold transport south of Texas. They escaped, but didn’t make it as far as they would have liked, getting snowed in at the Wichita Mountains in Oklahoma. They figured law enforcement wasn’t far behind, so they ditched the $2 million bounty somewhere in the Keechi Hills and moved on.

Thirty years later the first bits of gold were dug up by Jesse’s brother, Frank James. The retired outlaw hung around the Keechi Hills for nearly a decade attempting to retrace the gang’s steps and find small deposits of riches. He recovered some of the loot, but not nearly all of it.

The hunt for the James Gang’s cache intensified in the 1940s when treasure maps started to pop up around the state. Three were gifted to a James Gang descendant by a former gang member who was in his 80s and too old to search for “blood money.” Two more maps were discovered in the false bottom of a chest by a man who had bought the chest five years earlier. Another was found in an iron teapot by a treasure hunter looking for gold. Then there were the landmark clues, like rocks and trees, into which the gang scribed notes and symbols.

From big hauls, like a Dutch oven filled with gold bullion, to smaller finds like a brass pot with some jewelry, this isn’t your storybook sort of plunder. The trail for finding more stashes has largely gone cold, but hundreds of treasure seekers still visit the Keechi Hills every year with hopes of finding the next teapot full of doubloons.

Feature graphic via Hunter Spencer.