Vanishing Trails: The Battle for One of the West's Most Beloved Mountain Ranges

On October 21, 2021, during a Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources hearing, New Mexico Senator Martin Heinrich brought the microphone to his mouth, flipped his pencil around in his fingers, and accused U.S. Forest Service Deputy Chief Christopher French of yanking his chain.

“Mr. French, just the other day I raised the issue of the prescriptive public easements in the Crazy Mountains, and you said to me, and I quote, ‘We haven’t changed our position.’”

According to Montana law, a prescriptive easement is a right to use a piece of someone else’s private property that is acquired by using it openly and continuously for five years. This consistent use, which must meet a list of legal criteria, creates a public road or trail that cuts across private land but isn’t formally deeded. Prescriptive easements exist simply because public users have walked, ran, hiked, rode, or driven across them for a half decade or longer.

Montana’s Crazy Mountains are covered by a checkerboard of public and private land, an issue resulting from every-other-parcel land grants the government gave railroad builders along the lines they were constructing over a century ago. The USFS and the public have historically relied on prescriptive easements to access public land within the Crazies. Like lots of America’s prescriptive easements, four trails in the Crazies—the Sweet Grass, East Trunk, Porcupine-Lowline, and Elk Creek trails—have been in use for a long time, first showing up on USFS maps in 1925.

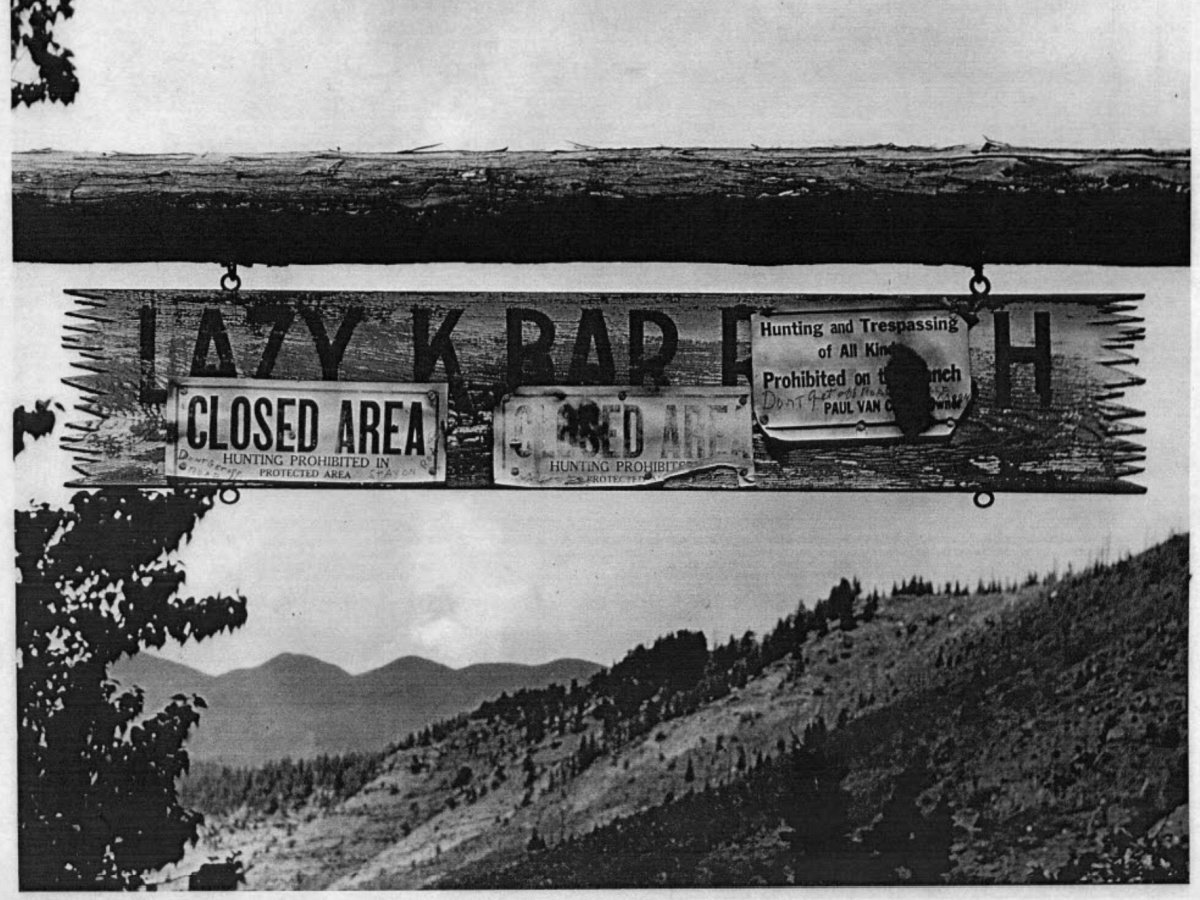

For the last 80 years, landowners in the Crazies have been accused of obstructing these roads and trails, posting “No Trespassing” signs, ripping down USFS signage and trail blazes, and threatening public users with trespassing citations and violence. The USFS’ “position” Sen. Heinrich referenced has long been to defend the trails against landowner interference and maintain these access points to some of Montana’s richest backcountry.

But in 2017, something changed. The USFS stopped removing landowner gates, obstructions, and “No Trespassing” signs. They stopped repairing their own trail signs and blazes. Members of the public were issued trespassing citations for using the trails without landowner permission. USFS Yellowstone District Ranger Alex Sienkiewicz, who oversaw the chunk of Custer-Gallatin National Forest within the mountain range and was considered by many to be a public access defender, was assigned a different position and internally investigated. So, in 2019, four Montana public access advocacy groups sued the USFS.

“But the Forest Service is not defending those easements in the current litigation,” Heinrich continued. “You tell me the Forest Service hasn’t changed its position, but your lack of action says more than words. I’m going to ask you again: Why is the Forest Service not defending the public’s access to their public lands?”

The 2019 lawsuit, filed by the Montana Chapter of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, Enhancing Montana’s Wildlife and Habitat, Friends of the Crazy Mountains, and the Skyline Sportsmen’s Association, claimed the USFS stopped protecting the four trails in question and failed their duty to the public in the process. The case landed in federal court in Billings on Jan. 18, 2022, and a month later, U.S. Magistrate Judge Timothy Cavan delivered a recommendation that shocked the plaintiffs: Not a single one of their claims held water. On April 1, District Judge Susan Watters confirmed Judge Cavan’s recommendation and sided with the USFS, saying the court couldn't compel the USFS to defend the trails.

As much as Americans value the idea of public lands, waters, wildlife, and access to all three, the United States was also built on private property rights. The opportunity to erect a fence around a plot of land and call it one’s own is at the core of what foreign settlers have found so attractive about this country for centuries. The Crazy Mountains aren’t the first place where two popular pieces of America’s blueprint—the public domain and the final clause of the 5thAmendment—have opposed each other.

But in the wake of the decision, public access advocates now fear they won’t be the last place where this happens, either. They’re worried this situation might be a cautionary tale for how other disputes over prescriptive easements are handled across Montana. And while some think the court decision put a hard stop to this saga, Montana Senator Jon Tester brought it up with current USFS Chief Randy Moore in a Senate committee hearing on May 4, signaling that the conversation is anything but over.

“The best habitat in the world is not worth much unless you can get access to it,” Sen. Tester said. “You don’t have to be a millionaire to be a hunter in Montana, because we all own those public lands. But if you don’t have access to them because it’s sealed off, then the public really doesn’t own those lands anymore. As far as the litigation goes…these guys aren’t crazy. They just want to make sure that they still have the ability to get in there and enjoy the great outdoors.”

A History of Defense

There’s nothing new about landowners blocking public access points that they don’t see as legitimate. Rancher Paul Van Cleve first locked a gate across Big Timber Canyon Road, which leads to the Half Moon Campground and USFS Trail #119 into the Crazies, during the 1940 hunting season. Then, in 1949, he accused a USFS road crew of trespassing, threatening them with a large rock and then with a rifle.

Landowners today mirror those sentiments and tactics. Montana Senator Steve Daines received a complaint from constituent Joe Rookhuizen, dated Sept. 24, 2015, about locked gates blocking the East Trunk Trail.

“I’ve called both Fish, Wildlife & Parks and also the Forest Service, both agencies agreed that it’s illegal what the landowner is doing, but are afraid of cutting the lock themselves, saying they don’t have support from their supervisors,” Rookhuizen wrote.

Sen. Daines likely acted on Rookhuizen’s behalf, even though no correspondence was ever made public, because he received a response from Forest Supervisor Mary Erickson on Oct. 2, 2015. She acknowledged the trail as “an illegally-blocked access point,” “designated as open to mountain bikes, hiking, stock, and cross-country shoeing uses in the 2006 Gallatin National Forest Travel Plan,” and as “a component of the popular ‘Lowline’ trail system.”

Regional Forester Leanne Marten published a memo in June 2017 with a similar message.

“A landowner on the east side of the Crazies has asserted that the United States does not have prescriptive rights on the East Trunk Trail. In letters to the landowner, the FS has made clear its view that the FS retains a prescriptive easement on the trail, which is shown on FS maps and served as a connecting trail between two historic FS guard stations,” she wrote.

Marten’s 2017 memo and Erickson’s 2015 letter to Sen. Daines are joined by a 2007 court declaration from Gallatin National Forest Lands Program Manager Robert Denee stating that “the Forest Service has chosen to identify the Porcupine-Lowline trail system, as well as several other trail systems crossing private lands, because the Forest Service believes the United States has an ‘easement interest’ in this trail system, and the Forest Service has a responsibility to manage this trail system under the Forest’s Travel Management Plan.”

Landowners vs. Land Users

One could argue this conflict has such a deep, inflammatory history because the opposing groups are fighting fundamentally different battles. The public access advocates argue that the USFS recently abandoned public access it had historically defended, proven by these examples of USFS leadership acknowledging the easements. But the landowners argue that such access was either abandoned long ago or never existed in the first place.

“While we don't believe any easements exist across our private property and exercise our rights to sign and protect our property, we love the mountains and know the public does as well,” the Carroccia Family told MeatEater. The Carroccias own and operate the Sweet Grass Ranch, a dude ranch, on their property. The same parcel was formerly owned by Paul Van Cleve.

“We, along with our neighbors, all frequently give permission for access through and across some of our private lands so the public can get to public lands,” they said.

The Carroccias are known to require that trail users check in with them and request permission to access the trails before venturing out. Some records of them making such demands goes back to March 1997. Other landowners have instituted the same rules, like Chuck Rein, a Crazy Mountain landowner, outfitter, and former president of the Montana Outfitters and Guides Association.

“Our private road called Rein Lane does indeed provide a means for the public to access the Forest Service lands that lay beyond our property,” Rein told MeatEater. “Rein Lane is recognized by Sweet Grass County as a private road. I do all of the maintenance on this lane, which is considerable given the amount of traffic that traverses it. We give permission for everyone to use our lane. We lock our gate and have people sign in if particular ranch activities require us to know who is traversing our land.”

But signing in to use a prescriptive easement technically undermines its validity. In the Forest Service Manual, the party claiming a prescriptive easement must use it in a notorious and adverse manner, which means using it without asking for permission first. This is what makes prescriptive easements so tricky for public users: establishing and maintaining one requires behavior that could be considered trespass if prosecuted. That’s also why use and protection by federal agencies is so important.

This method of creating access clearly worked in the 19th and early 20th centuries when most of America’s prescriptive easements were first established. But today, public users fear some of these trails will never be publicly accessible without landowner permission again.

“We at Rein Anchor Ranch recognize the need for the public to access public land,” Rein said. “Thus, we have tried to be a good neighbor by providing access free of charge to the general public.”

According to Montana historian and public lands advocate Andrew Posewitz, by erecting gates and signs and requiring permission for access, the landowners weren’t just trying to prevent public users from walking across their land. If a prescriptive easement isn’t used and maintained continuously for five years, it’s considered abandoned under Montana law.

“Landowners block the trail and they hope after five years that you have abandoned the trail and then they can walk in and make their abandonment claim,” he said. “But in this case, the public hasn’t been failing to use the trails because they abandoned them. It’s because they don’t want to take their lives into their own hands.”

The Sienkiewicz Controversy

These intricacies were the focal point for a series of memos Alex Sienkiewicz had written to his rangers throughout the early 2010s. Then, on July 7, 2016, a Facebook user named Lee Gustafson leaked one of those memos onto the Public Land Water Access Association Facebook page.

“All—This is my regular reminder: NEVER ask permission to access the national Forest Service through a traditional route shown on our maps EVEN if that route crosses private land. NEVER ASK PERMISSION. NEVER SIGN IN (concerns—come see me). This Includes BUT IS NOT LIMITED TO: -Sweet Grass Creek (Carrocia, Rein attempting to extinguish public access) -Anywhere on the Lowline Trail (east and west Crazies) (Zimmerman, Guth, Groff, Languis, and others trying to extinguish public access) -Swamp Creek (Grosfield trying to extinguish public access) -16 Mile north crazies Whatever past DRs or colleagues have said, I am making it clear. DO NOT ASK permission and DO NOT ADVISE publics to ask permission. These are historic public access routes. By asking permission, one undermines public access rights and plays into their lawyers’ trap of establishing a history of permissive access. Again, questions, concerns, come see me.”

Eventually, landowners in the area saw Sienkiewicz’ note. On Dec. 30, 2016, landowners Lorents Grosfield, Ned Zimmerman, and Chuck Rein wrote a letter to Forest Supervisor Erickson, attaching a screenshot of the Facebook post and accusing Sienkiewicz of giving legal advice to his team of rangers without being licensed to practice law in Montana. They cc’d Regional Forester Marten, U.S. Representative Ryan Zinke, Sen. Tester, and Sen. Daines.

A month later, John Youngberg, the executive VP of the Montana Farm Bureau Federation, wrote a different letter to Sen. Daines expressing concern about the Facebook post, of which he also attached a screenshot.

“Senator, could you please investigate whether the Forest Service and Ranger Sienkiewicz acted appropriately in regards to the Facebook post and what recourse the private property owners in the Crazy Mountains have in stopping what we see as a broad over-reach of the District Ranger’s authority and if indeed it is Forest Service policy to encourage trespass to gain prescriptive easements,” the letter read. “This kind of action does little to promote landowner/sportsman relations and in the end will do nothing to open up increased access to public lands.”

Sen. Daines wrote a letter of his own to then-USFS Chief Tom Tidwell on May 26, 2017. Farm Bureau VP Youngberg’s letter was attached.

“As noted in the attached, the perceived directive coming from the USFS seems to promote controversy and aggressive action rather than the collaborative approach we all strive to achieve as public servants,” Daines wrote. “I am concerned that a lack of clarity on how to manage disputed access points presents problems for both agency personnel and landowners, which ultimately hurts not only local stakeholders, but also the general public.”

Sienkiewicz was reassigned and reviewed internally less than a month later.

Sen. Daines’ office told MeatEater they had no involvement in the personnel matter that resulted in Sienkiewicz’ removal. Spokesperson Katie Schoettler noted that Sen. Daines has a long history of advocating for public access, specifically in his championing of the Great American Outdoors Act, the Land and Water Conservation Fund, the MAPLand Act, and others. He also recently won the James D. Range Conservation Award from the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership for his work protecting public access to public lands.

“The dispute surrounding the Crazy Mountains is very complex, dating back several decades, with legitimate concerns from constituents on both sides of the issue. Senator Daines met with constituents on both sides of this issue, as he does on all issues impacting Montana,” Schoettler told MeatEater. “As far as the removing of Ranger Sienkiewicz, that’s untrue. Our office was explicit in saying the Senator would not entertain any specific issue related to internal personnel matters.”

Shifting Policy and Battling Abandonment

Public access advocates feel that the USFS has reversed their position on protecting prescriptive easements without publicly announcing such a change in agency policy.

“The USFS has completely revised their approach in the Crazy Mountains, and they continue to deny that they're doing it,” Posewitz said. “They stopped defending them and they have not acknowledged it.”

The USFS denies any recent change to how it handles prescriptive easement disputes.

“There has been no change in Forest Service policy regarding how we work to resolve complex access issues. There is not nor has there ever been a one-size-fits-all approach to addressing historic routes and disputed access,” Marna Daley, public affairs officer for the Custer-Gallatin National Forest, told MeatEater. “For the trails in question, these disputes go back decades. Agency policy encourages local managers to use all tools to resolve access disputes: negotiation, purchase of easements, cooperative, and reciprocal access agreements, or establishing existing rights through a court decree.”

In Judge Watters’ decision from April 1, she said that even though the four trails in question have shown up on USFS maps since the early 1900s and the USFS historically believed they possessed prescriptive easement interests in them, the USFS no longer had a duty to protect and uphold such access because the easements were never deeded.

“The Forest Service has never secured a perfected easement interest in the trails, and private landowners have long disputed Forest Service Access rights to these trails on private property,” she wrote.

According to the Forest Service Manual’s Region 1 Issuance 5460, “Title to an easement acquired by prescription is as effective as though evidenced by a deed.” So how could prescriptive easements be any less qualified for protection? According to Posewitz, to even ask such a question is to deny what is widely considered a historically proven fact: prescriptive easements absolutely provide legal public access and are a legitimate interest of whatever agency claims them on the public’s behalf.

After all, as Posewitz pointed out, if prescriptive easements didn’t create such access, then landowners wouldn’t need the two available legal mechanisms to dissolve them.

“If you want to remove a prescriptive easement from your property, you have two choices. You can file a quiet title. There is a statute of limitations on a quiet title. In the case of these trails, that time has expired. That's not a viable option for these landowners,” Posewitz said. “Or, if the public abandons that trail or road for five years, that would then eradicate the easement off your property. Those are the only two ways that a landowner can remove a prescriptive easement.”

Brad Wilson, a lifetime resident of the area, former sheriff’s deputy, and one of the leaders of Friends of the Crazy Mountains, fought to keep such an abandonment claim from becoming possible.

“A group of us up here in Ground Zero as I call it, in the Crazy Mountains on the north end, always set up a hunt camp during general season. For the last several years we've hunted up there and a lot of our trails are becoming so hard to get through. They've just let it go. A lot of us had, prior to this, cleaned a little bit so we could get in and out of there,” Wilson told MeatEater.

Recent examples of trail activity and maintenance were used as evidence that the trails hadn’t been abandoned by the public.

“I finally got to meet with Alex Sienkiewicz and explain to him we wanted to go in and start cleaning trails. He became ecstatic. He said, ‘Oh, absolutely. We just love volunteers coming in,’” Wilson said. “And then, all of a sudden, we heard rumors he was going to be reassigned. At that point is when things really started falling apart. It seemed like the USFS just sat by idly while landowners blocked gates. They did nothing to go in there and try to contest it or change it.”

America’s Public Lands

Sen. Heinrich brought up this dispute in the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources hearing for a reason. He was concerned about the precedent it could set for the rest of the country.

“We all have these t-shirts that say ‘Public Land Owner,’ but that’s American public land,” Sen. Heinrich told MeatEater. “Teddy Roosevelt cast this die over a hundred years ago, and because of it, my children have this amazing public heritage that is not limited to the state they were born in. The public lands in Alaska and Montana and Michigan belong to them every bit as much as the public lands in their home state of New Mexico.”

That may be so, but the Custer-Gallatin National Forest is a standout example of how difficult it is to access checkerboarded public land.

“I remember Randy Newberg was forced to use either a helicopter or a light aircraft to get into the Crazies to avoid the rules over corner jumping and landowners shutting down access,” Heinrich said. “And that resonated with me because when I’m mule deer hunting, I’m navigating this checkerboard of state, private, Forest Service, and BLM lands, and then when you layer on top of that historic roads and trails that are suddenly in question, huge amounts of public ground become very difficult to access. I’ve seen roads shut down, gated, and locked.”

The plight of the prescriptive easement doesn’t start and end with locked gates, landowner signs, and federal lawsuits. The East Trunk Trail is the subject of a massive land-swap deal, a brainchild of the multi-stakeholder Crazy Mountain Access Project that involves trading Crazy Mountain land with the Yellowstone Club of Big Sky, Montana. A rerouted version of the Porcupine-Lowline trail opened to the public in October of 2021.

Public access advocates fear that a much larger trend is emerging here, one that the most recent lawsuit—and the subsequent decision—reveal. Perhaps this could happen anywhere across the state, to any prescriptive easement.

“The ruling is merely a speed bump in this bigger fight to preserve access, not just in the Crazies, but across the West,” John Sullivan, board chair of the Montana BHA chapter, told MeatEater. “The education that the ruling affords us highlights the real problems that we're going to keep running into in the future.”

Maybe the Crazy Mountains aren’t all that crazy. Maybe they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

Feature image via Brad Bolte.