Nearly 60 million acres of federal public lands in Alaska may close to non-resident and the vast majority of resident hunters if a new proposal is approved by the Federal Subsistence Board. The Northwest Arctic Subsistence Regional Advisory Council is seeking to limit harvest of caribou and moose in game management units 23 and 26A during August and September of 2021 to only qualified subsistence hunters that reside in those remote areas at the northwestern corner of the state.

“The Council is very concerned about the late migration of caribou through Unit 23 because local people rely upon caribou to meet their subsistence needs,” Temporary Special Action Request WSA21-01 states. “The Council is particularly concerned about the effect transporters and non-local hunters are having on the migration of the Western Arctic Caribou Herd and believe that transporter activity in Units 23 and 26A may be delaying caribou migration. The Council hopes this request would reduce aircraft traffic, creating an easier path for migrating caribou. The Council also supports closing moose hunting to non-Federally qualified users because of declining moose populations.”

The NWASRA council is made up of representatives from rural communities throughout the region like Kotzebue and Ambler, as well as officials from all federal agencies with holdings or interests in the area. The Federal Subsistence Board, which will review the proposal, is made up of the regional directors of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Indian Affairs, the U.S. Forest Service, plus three public members appointed by the Secretaries of the Interior and Agriculture, two of which must represent rural subsistence users. These bodies were formed by the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), signed by President Carter in 1980, which provided various designations and protections to 157 million acres of federal ground in Alaska, giving us much of the system of refuges, parks, wildernesses, and forests we know today. Of note, section 804 of ANILCA also accords priority to subsistence use of fish and wildlife over all other purposes.

While the federal government appears to endorse the temporary special action request to prevent non-local hunters from pursuing caribou and moose in about 27% of the federal ground in Alaska, the state government is strongly opposed. The Alaska Department of Fish & Game is already fighting a similar decision in court from last year regarding GMU 13 and they plan to take the same action if the present proposal is approved.

The assistant director of ADFG’s Division of Wildlife Conservation, Tony Kavalok, told MeatEater that he and his department are not aware of any biological data supporting the council’s desire to keep non-local hunters out for wildlife management purposes.

“We do not see this as a biological decision,” Kavalok said. “It's a political decision. It has to do with conflict between user groups.”

Indeed, the council members did cite conflict with outsiders at the virtual meeting in February. Chairman Enoch Shiedt Sr. of Kotzebue in his report noted “that he feels that outside hunters chased off the caribou, and local hunters suffer and need meat as a result.” Council member Barbara Atoruk of Kiana said. “Many local people were treated badly and called names by outsiders.” COVID-19 is still spreading in the region, which some blame on visitors.

This conflict has been simmering since the early 1980s, with locals accusing the air traffic from outsiders for diverting and delaying historical caribou migration routes that subsistence hunting families rely on for meat. The 1988 creation of the Noatak Controlled Use Area closed a corridor of 5 miles on either side of the river to any use of aircraft in any manner with any connection to big game hunting. That no-fly zone has since grown, and others have been proposed.

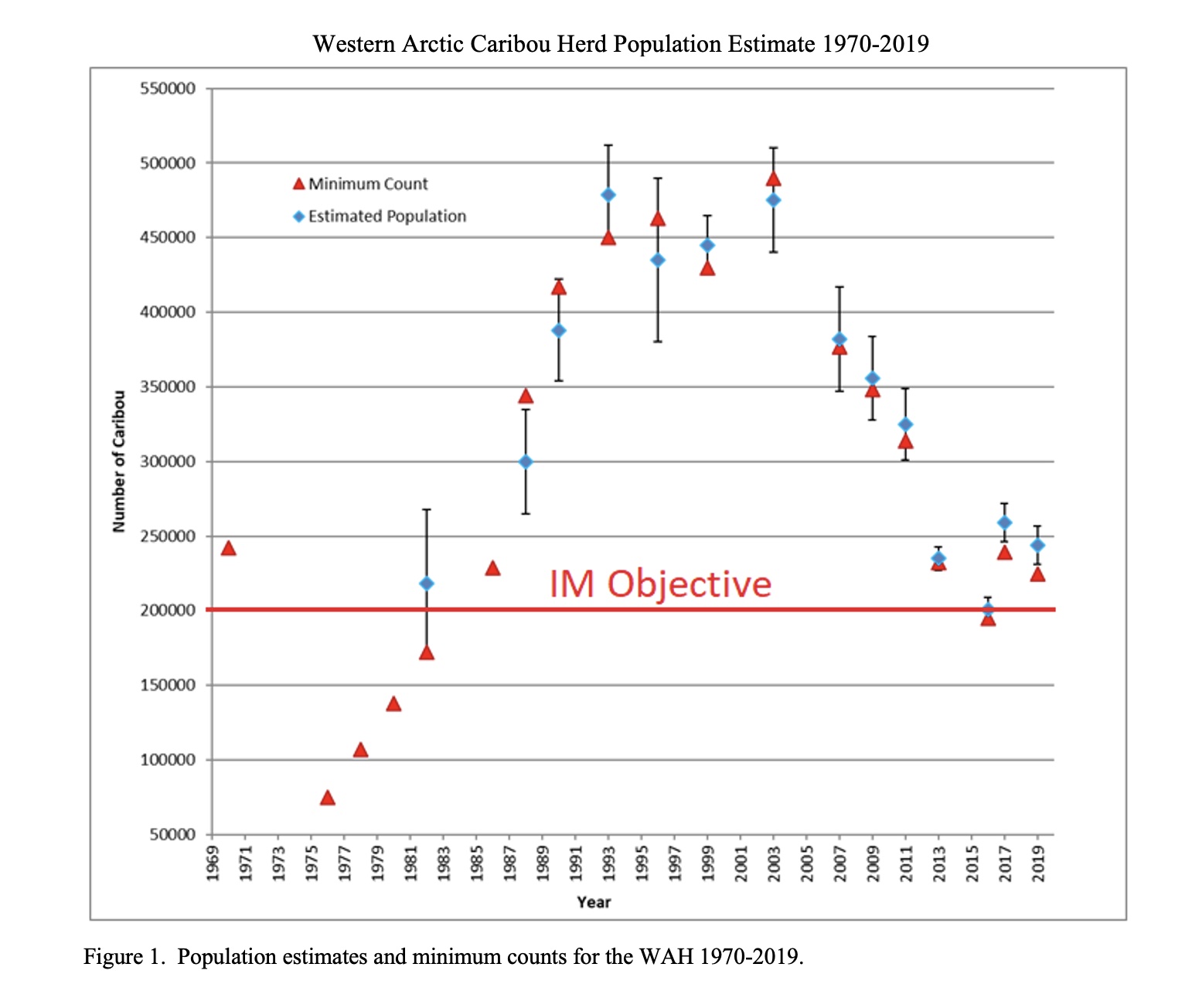

As for hunting, the Western Arctic Caribou Herd is considered stable and healthy by ADFG, with the most recent population estimate of 244,000 head in 2019. That is down from a historic boom near 500,000 individuals in 2003, but numbers have been on the rebound in recent years and remain well above the threshold of conservation concern. The smaller Teshekpuk Herd reflects similar trends. Biologists also consider the moose populations stable in these areas.

ADFG roughly estimates annual total harvest of caribou in this region at 12,000 for the Western Arctic Herd and 3,500 for the Teshekpuk. Of that, resident Alaskans not qualified for subsistence hunting there killed an average of 64 animals a year between 2017 and 2019. Non-resident hunters shot an average of 212 caribou per year in that same 3-year timeframe. Taken together and adding another 30 to 50 animals killed by non-subsistence hunters every year in GMU 26, the ADFG estimate states: “Combined average harvest for NFQSs (non-federally qualified subsistence users) for both herds between 2017 and 2019 was between 300 and 350 caribou which equates to approximately 2.5% of total harvest.”

“That is such a small number,” Ben Mulligan, deputy commissioner for ADFG, told MeatEater. “You're looking at 2.5 to 5% of the animals taken out of that herd are done by non-federally qualified users, which is such a low percentage. We can’t imagine that those folks who are up there have such a dramatic impact on the migration of the herd, which is what they're saying is causing their lack of subsistence opportunity because the herd is migrating differently over the years.”

Mulligan pointed out that just removing hunters wouldn’t entirely solve their problem if they’re saying that plane traffic is what’s causing the migratory shift. Public lands and conservation advocacy group Backcountry Hunters & Anglers also suggested that the proposal doesn’t address the real issues at play.

“The claim that the migration of caribou is being delayed by unusual conditions is not being challenged. However, the information available to support the claim that increased air traffic is the primary cause of migration delay is minimal,” BHA said in their public comment opposing the council’s request. “Further, the falling number of non-local harvest since 2016 would indicate less air traffic. Significant factors like climate change have been cited by local residents, management groups, and agencies as areas of management concern and possible causes of delayed migration. This special action request does nothing to address that issue.”

Like many hunters and hunting groups involved, BHA urges the Federal Subsistence Board to follow the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation in this case.

“BHA believes that management of our fish and game populations should be guided by current, peer-reviewed science. Presently there is no biological concern to merit the proposed closure, with no significant information available to support the assertion that air traffic has delayed caribou migration. Over the last two decades, subsistence harvest of caribou has remained high and above population objective targets that would warrant action.”

These two game management units don’t contribute greatly to non-subsistence resident and non-resident caribou and moose harvest numbers statewide. Still, Alaska game managers are concerned that this closure, even though it would only be authorized for one year, could increase crowding elsewhere in the state and cause uncertainty about opportunity going forward. Even more so, they worry that the nine other regional subsistence boards might adopt similar strategies if this precedent is set. Kavalok says similar regulations have been implemented for blacktail deer in Southeast Alaska near the village of Kake.

Alaskan officials also say that this potential public lands closure to non-local hunters amounts to federal government meddling in state management of wildlife—a frequent accusation in recent years seen also in controversies surrounding the National Park Service banning traditional hunting methods like “denning” bears, killing caribou from boats, and baiting bears, against the wishes of ADFG and many Alaskans.

“If you care about hunting moose and caribou in Alaska, you need to keep your eye on this one,” Kavalok said. “Because this is just the latest erosion, but it's a big step. If this is able to get through the court system and pass muster and then be put into a law down the road, it's only the first step because other rural local advisory committees may catch on and want to do the same thing in their communities throughout other parts of Alaska. Sixty-plus-percent of our land is federal land, so you can see where this is going.”

No one is certain how the Federal Subsistence Board will rule on the temporary special action request. Already the board has acknowledged the high degree of public attention on the proposal by adding a five-day written comment period beginning April 16 in addition to the already-scheduled public hearing on the April 23 5 – 7 p.m. Pacific. They will be taking verbal comments at that hearing, which anyone may attend at 877-918-3011 with passcode 8147177.

“We encourage everyone who has concerns to call into a public hearing or submit comments during the comment period on this special action request,” Caron McKee, outreach coordinator at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Office of Subsistence Management, told MeatEater via email. “After the public hearing, OSM staff will compile all public comments to present to the Federal Subsistence Board, the Board uses the analysis, which addresses biological and anthropological data and public comments to make their decision.”

Many hunters in Alaska and across the country are concerned about the precedent that could be set by this closure. Many are also sensitive to the needs of communities that truly live off the land and have for thousands of years. Food is incredibly expensive to buy in rural Alaska. Above all, there is no need for disrespect between hunters, whether they seek subsistence or sport. MeatEater founder Steven Rinella echoed these problems.

"My biases on this issue are obvious: I'm a non-resident who owns a hunting and fishing shack in Alaska, and I spend a month or so every year bouncing around the state in pursuit of game—including, one year, in the area affected by this closure,” Steve said. “So, naturally, I'm gonna get alarmed by an action that shuts out the overwhelming majority of American hunters—both non-resident and resident—from millions of acres of our federally managed public land. But this issue goes behind what's good or bad for me, personally. It touches on a concerning trend in wildlife management, where hunters are excluded from exploiting renewable resources due to social concerns, even in cases where there's no legitimate concern for the sustainability of that resource."