There’s a difference between book smart and bar smart. You may not be book smart, but this series can make you seem educated and interesting from a barstool. So, belly up, pour yourself a glass of something good and take mental notes as we look at the genesis of the jackalope.

Growing up in South Dakota, many of my childhood vacations featured a stop at the infamous Wall Drug. As I looked through gift shops with endless shelves of Western-themed trinkets, I often paused when I came across any souvenir featuring a jackalope. Even though I was pretty sure that jackalopes weren’t real, the taxidermied cottontails with little antlers just seemed too convincing to my young eyes. I was never brave enough to ask any adult whether these unusual creatures were an actual species, but I eyed any depiction of them suspiciously.

Most adults, although of course not all, know that jackalopes are the stuff of legend. Yet, we’re still captivated by these mythical beasts. We see jackalopes in art, gas stations, and occasionally even featured in bills brought up by state legislatures. But given that they’re widely accepted to be mythical creatures, imagine how surprised I was to see a jackalope preserved in the mammal collection at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History! As it turns out, naturalists have been documenting horned rabbits for nearly 800 years.

The “jackalope” in the Smithsonian was a cottontail that had been infected with Shope papilloma virus. This disease is related to the human papillomavirus, and it causes hard, dark warts to grow on a rabbit’s face. Many people have speculated that the legends of jackalopes might have originated from seeing a rabbit infected with this virus. It’s not hard to imagine someone drinking libations around a campfire, catching a glimpse of a warty rabbit in the dim light, and then telling all of their buddies the next day about seeing a jackalope.

This virus was first scientifically described by virologist Richard Shope in 1933. Hunters from Iowa brought him warty cottontails, which Shope then used for experiments to better understand the disease. Since then, scientists have detected the virus in museum specimens and live-captured animals from the Midwest and Western U.S. Although it appears to have a wide distribution, the virus actually appears very rarely. Cottontails, domestic rabbits, snowshoe hares, and jackrabbits can all get the virus, either naturally or through exposure during experiments. One could interpret this to mean that, although seeing one is rare, there are many subspecies of jackalopes running around out there.

Although the warts can grow large enough to prevent a rabbit from eating, the virus isn’t usually fatal and most rabbits clear it in under a year. Studying Shope papilloma virus has provided important insight on jackalope ecology, but it also has provided a useful system to better understand how cancer affects humans. However, humans can’t acquire this form of the virus and, in fact, some say that it’s OK to eat rabbits that are infected with the virus. That’s right: if you’re lucky, and maybe bold, you could tell your friends that you’ve tried jackalope meat.

The 1930s were an important decade for those of us interested in American jackalopes. In addition to advances in understanding Shope papilloma virus, Ralph and Douglas Herrick, taxidermists in Douglas, Wyoming, admitted to conjuring up the American jackalope that we know today. After returning from a hunting trip, the Herrick Brothers serendipitously noticed a dead jackrabbit lying next to a pair of antlers on the floor of their taxidermy shop. They decided to mount the rabbit with antlers and then sold their masterpiece to a hotel owner. This might explain why jackalopes often have deer antlers, not pronghorns as the name would suggest. Over time, Douglas, Wyoming, became known as the Jackalope Capital of the World, and eventually put up an 8-foot jackalope statue in the city center. As word of this strange creature spread and drew visitors, the stories and descriptions only grew. Experts on the American jackalope will recall that these animals are especially fond of whiskey, only breed during lightning strikes, and produce milk that is a powerful aphrodisiac. A clever taxidermist might have created the version of jackalopes that we’re most familiar with, but Shope’s work showed that jackalope-like rabbits really do exist.

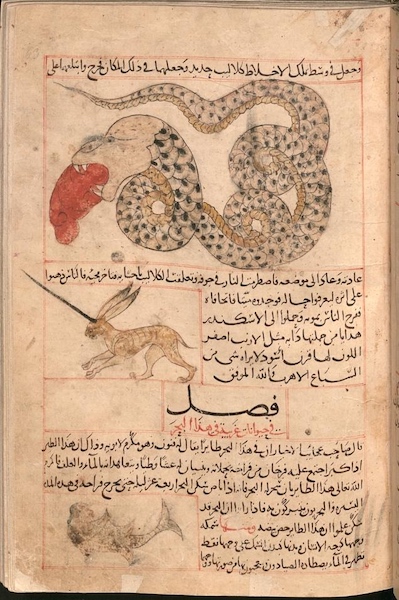

We tend to be particularly drawn to jackalopes in the Western U.S., but rabbits with growths on their heads have been on our minds for centuries. Depictions of rabbits with headgear go all the way back to Persian texts from the thirteenth century. In “The Wonders of Creation,” published around 1280 AD, naturalist Zakarīyā Ibn Muḥammad al-Qazwīnī included an image and description of Al-Mi’raj, a ferocious rabbit with a single horn.

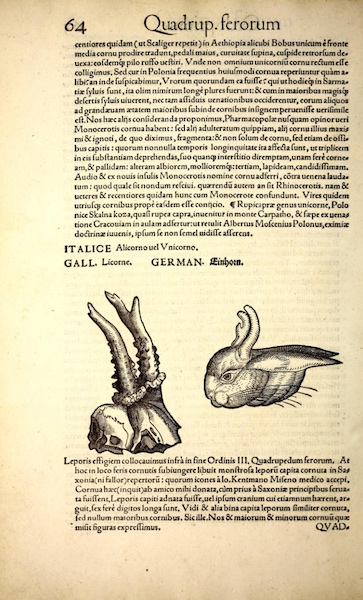

In 1560, Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner included a rabbit with horns, or Lepus cornutus by its scientific name, in his description of what were thought to be real animals from around the world. In historical accounts, horned rabbits are nestled in between descriptions of bears, elephants, sea serpents, and unicorns. When scientists were working without computers in their pockets, it must have been hard to distinguish a real animal from a mistaken observation. As people cataloged the world around them, perhaps the horned rabbits they described were rabbits that had been infected with some sort of wart-inducing virus.

At this point, we can’t say for certain whether our centuries-old interest in horned rabbits is based on observations of a rabbit infected with a papilloma virus or if they were mythical creatures conjured up by imaginative minds. With jackalopes, like many other fantastical animals, reality and mythology mix in a hazy combination of observation and rumor. Even so, it’s fun to imagine that jackalopes really are somewhere out on our Western prairie, drinking whiskey and sparring during the rut.

Featured image courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.