The history of wild game management in the United States is something that all hunters and anglers should be familiar with. An interesting relic of this story is this Colorado hunting and fishing pamphlet from the year 1917. It shows us some interesting and peculiar details about hunting and fishing at the time. It also teaches us a lot about the roles that conservation and fish and game management have played in providing today’s hunters and anglers with so many incredible opportunities.

A century ago, people were just beginning to understand fish and game weren’t unlimited resources. American fish and game management was a fledgling concept stemming from conservation models brought forth by forward-thinking outdoorsmen like Theodore Roosevelt and William Hornaday. As the days of unregulated market hunting were coming to an end, many newly formed state fish and game agencies were tasked with managing dwindling wildlife resources for future sustainability.

Suddenly, hunters and fishermen accustomed to unregulated hunting and fishing were faced with new legal requirements. These laws mandated that hunters and anglers must possess licenses and follow strict bag limits and seasonal closures. These newly enacted regulatory measures were critical to ensuring a future for hunting and fishing in America. Some game animals were barely hanging on at the time and it became apparent that only aggressive management efforts might prevent them from disappearing from the landscape.

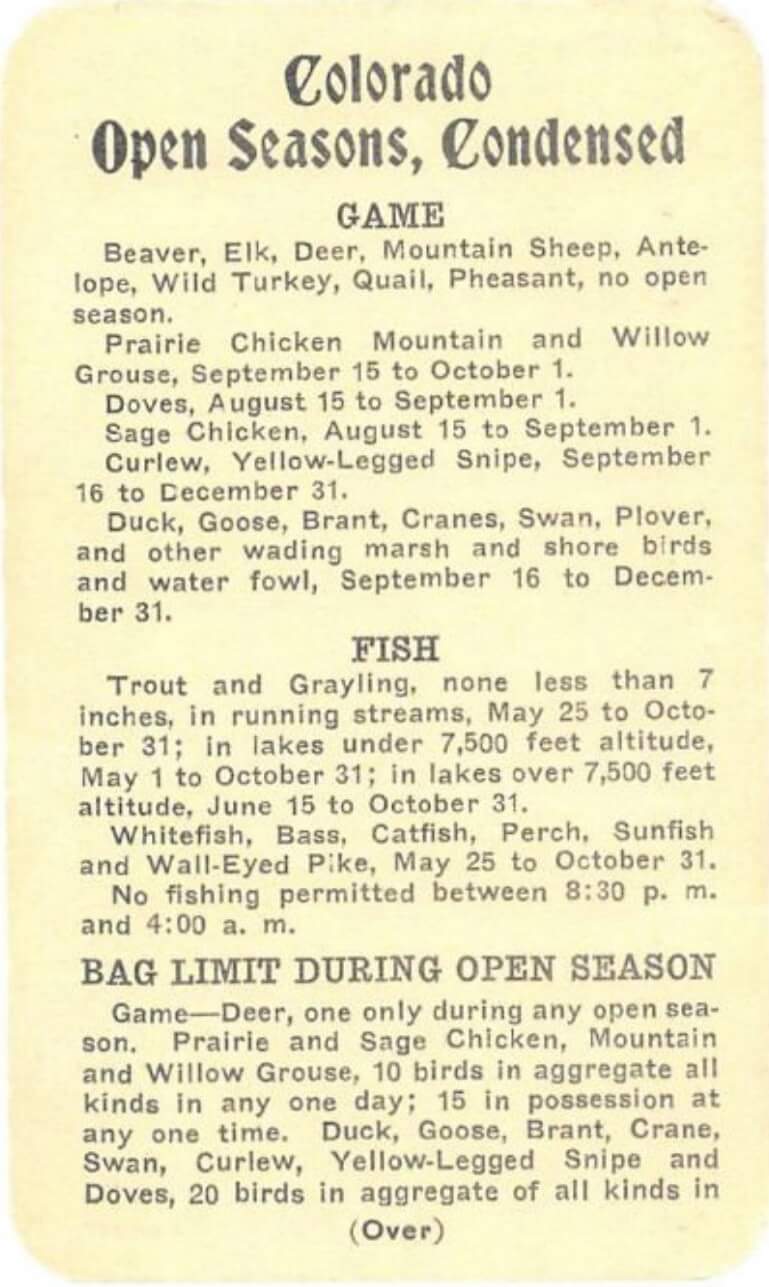

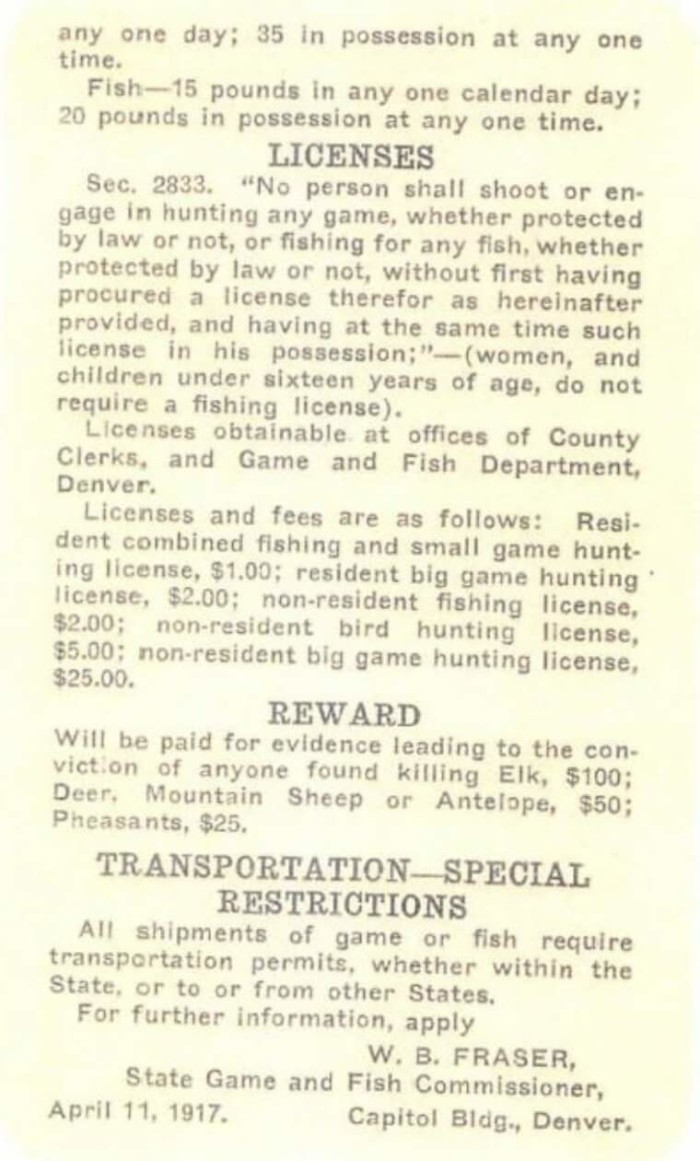

Today, it’s difficult to imagine not having any elk or turkeys to hunt, especially in such a renowned hunting location as Colorado. At the time though, elk, bighorn sheep, pronghorn antelope, wild turkeys, even quail and beavers had been eliminated from much of their historic range in Colorado. Recognizing immediate action was needed to protect these animals and hopefully restore populations, Colorado’s wildlife managers made it illegal to hunt any of these species. The state even offered rewards for evidence that led to the conviction of anyone killing an off-limits animal.

In contrast to species with vulnerable populations, waterfowl were managed much more liberally. Daily bag limits allowed a Colorado hunter to kill twenty of any waterfowl species a day, in aggregate, which is roughly three times the current limit. Even more astonishing to a modern waterfowler, those same regulations permitted a hunter to kill twenty swans or cranes in a single day. Wildlife managers soon recognized those overly liberal bag limits were unsustainable and waterfowl hunting became more strictly controlled in 1934 with the passage of the Migratory Bird Act and the introduction of the Federal Duck Stamp.

There is also an interesting and conspicuous absence of certain animals in Colorado’s 1917 regulations. Mountain goats and moose had not yet been introduced into Colorado. Bears and mountain lions are not listed anywhere, perhaps because they were regarded as vermin, not a game animal. Interestingly, besides beavers, furbearers are also not addressed. Bobcats, mink, foxes and other furbearers might also have been considered vermin. Small game such as rabbits and squirrels didn’t seem to warrant regulations either.

Colorado apparently had only a single law not directly related to species, bag limits and season dates. All hunters and anglers aged 16 or older had to be legally licensed. More familiar modern laws didn’t seem to exist. Concerning method of take, there were no separate archery or rifle seasons. Legal shooting hours are not mentioned. Hunters did not have to wear fluorescent orange nor was hunter education a requirement. There was no law regarding the take of antlered or antlerless deer. All of these absences are mind boggling to a modern hunter who must adhere to massive suites of rules governing everything from complex season structures and minimum legal calibers to providing evidence of sex and statistical harvest data.

The differences don’t just concern hunting regulations. You’ll also see notable variances from today’s fishing laws in Colorado’s century-old regulations. Various fishing seasons were only open for a few months from late spring until the end of October. Trout and grayling season dates were based on elevation for reasons I don’t completely understand. Bag and possession limits controlled poundage instead of numbers of fish. Night fishing was illegal, probably to prevent poaching.

Today’s hunters and anglers might scratch their heads considering these two short pages of regulations littered with oddities. But, it is important to understand that however abbreviated or incomplete these regulations might appear now, this was an important step towards successfully managing fish and game resources. The same success that resulted from Colorado’s early fish and game laws played out across the country. Over time, laws governing fish and game would not only become more intricate but also more effective.

These days, Colorado’s fish and game management covers everything from bluegills and bullfrogs to moose and mountain lions. Each species demands different management goals. Colorado currently has separate regulations brochures for fishing, small game, turkey, mountain lions, sheep and mountain goats, and all other big game. The big game brochure alone runs about 70 pages. With additions and changes to rules occurring frequently, it is necessary for hunters and anglers to carefully study each set of regulations every year.

When I received Colorado’s 2017 Big Game Brochure in the mail this morning, I imagined an old timer back in 1917 griping about the restrictive nature of Colorado fish and game laws. A century later I’m looking forward to reading the latest regs booklet to see what’s new and start planning this year’s hunts. And, I’ll take a minute to reflect on past regulations that made it possible for me to enjoy the endless hunting and fishing opportunities in America today. The next time you are tempted to lament the good old days, remember how far we’ve actually come.

Brody Henderson is a hunter, fly fishing guide, writer, wilderness production assistant for the MeatEater television show and MeatEater‘s editorial contributor.