Inside the Debate: The Impacts of the Proposed Idaho Steelhead Closure

So far this year, 53,000 steelhead have passed the fish ladders of Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River, the last place where they can be counted on their return upriver from the Pacific through Washington and into Idaho. Twelve thousand of those were Endangered Species Act-protected wild steelhead, the rest being of hatchery origin.

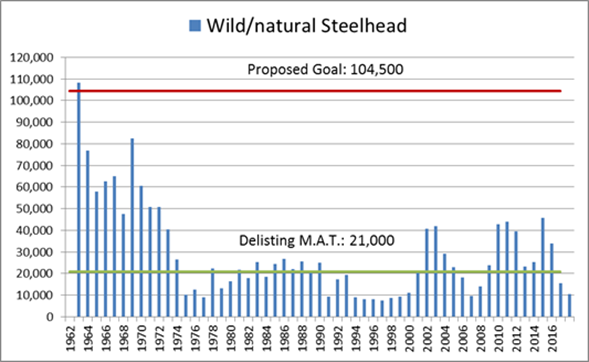

You’d have to reach all the way back to 1994 to find a smaller wild steelhead return to Idaho. The wild population has been in sharp decline for four years and stands at only a quarter of the 10-year average of more than 40,000. Idaho used to receive upwards of 100,000 wild steelhead every year. Predictions suggest that less than 1,000 of Idaho’s large, famous “B-run” native steelhead, those bruisers that can stretch the tape past 40 inches, will swim the Salmon and Clearwater rivers this year.

That much, at least, most people agree upon.

On Oct. 9, six conservation groups gave 60-day notice of their intent to sue the Idaho Department of Fish & Game. The Conservation Angler, Wild Fish Conservancy, Idaho Rivers United, Friends of the Clearwater, Snake River Waterkeeper and Wild Salmon Rivers asserted that Idaho has been operating a steelhead fishing season without the incidental take permit required under the Endangered Species Act for a mixed-stock fishery involving ESA protected fish. The state has applied for a new permit from the National Marine Fisheries Service every year since it expired in 2010, but the federal government has only now begun to review the application, although they have issued permits for the operation of Idaho’s steelhead hatcheries.

With the threat of litigation, these wild fish and river groups sought to force Idaho to reduce harm to what few wild steelhead remain in the state by adopting more stringent fishing regulations. They felt previous calls to do so had been ignored. In negotiations on November 8, the groups put forward measures that would require only single point, barbless hooks and that wild steelhead be kept in the water before release, among other requirements that were taken off the table. Such rules are increasingly common in the other three continental states with true anadromous steelhead.

Idaho labeled these demands social issues rather than conservation measures and refused to budge. The negotiations fell apart. On Nov. 14, the Idaho Fish & Game Commission voted to close all steelhead fisheries in the state effective Dec. 7—60 days after intent to sue was filed—to avoid a legal battle they would likely lose. A provision of the ESA allows for plaintiffs to recover legal fees from the government after a successful challenge—a cost the state did not want to incur on top of their own fees for defense.

The Pacific Northwest angling community erupted over the closure. Residents of Riggins and other fishing-dependent communities put up signs saying the conservation groups were not welcome. Fly anglers responded in outrage to videos of conventional anglers hoisting wild steelhead high out of the water. Under pressure, Idaho Rivers United dropped out from the litigation. Blame and anger flew in every direction.

On the Dec. 3 episode of the MeatEater Podcast, IDFG Director Virgil Moore expressed a great deal of sadness about the closure his department enacted and the economic effect it would have on towns like Riggins.

“The closure of the winter steelhead fishery is millions of dollars to that community that is probably getting a third of their financial revenue from steelhead fishing, another third from Chinook and the rest from other outdoor-based recreation activities,” Moore said. “It hits a community like that hard over Christmas. Goodness, who’s the Grinch here?”

On Dec. 7, the same day the closure was supposed to take effect, Idaho reached a settlement with the wild fish groups. The state would close fishing on remote stretches of the Salmon and South Fork Clearwater rivers to protect wild fish, as well as reduce the bag limit to one hatchery steelhead per day. The National Marine Fisheries Service began work on Idaho’s permit and is expected to take action prior to March 15, 2019. Some of Idaho’s recreational fishing groups established their own set of voluntary regulations to reduce impacts on wild steelhead.

All of these actions staved off a devastating closure, but some wounds do not heal quickly.

“Part of their agenda, they were willing to not sue us if we agreed to go to no bait, single barbless hooks, fly fishing only, ban the use of boats,” Moore said. “They were trying to say this was a conservation issue, but they had this string of things that would have precluded most of our steelhead anglers from going fishing just so that group could get out there, the catch-and-release group basically.”

David Moscowitz, executive director of the Conservation Angler, one of the litigants in the threatened lawsuit, says Moore’s assertion is patently false.

“The idea that we’re trying to make these rivers fly fishing only, that’s total bull,” Moscowitz said. “Virgil is absolutely wrong. I’m sure those guys got together and decided that was going to be their message and it definitely resonates if you’re a gear guy or a bait guy in a boat in Idaho. But we all bear responsibility when these fish [populations] get to be so low. That’s what motivates us.”

Moscowitz, who says he regularly fishes for steelhead with a spinning rod (when it’s too windy to Spey cast) says that he and his colleagues know that it’s not anglers who are having the biggest impact on wild steelhead. The eight dams steelhead must pass both ways to and from the Pacific, poor ocean conditions, high water temperatures and increased predation in the Columbia and Snake, all contribute to their decline.

“The fish getting back to Idaho are the ones that made it through every single one of these major insults to their survivability,” Moscowitz said. “These are the fish that made it past the hordes of anglers, they made it past people like me, they made it past the tribal nets and they get to Idaho.

“For the past few years we’ve been basically under a thousand wild B-runs. These are the big ones that everybody wants to catch. It’s an incredible fish, it’s an incredible animal. We feel that with the low numbers, there should be a change in how they’re fished for. Idaho was completely resistant to that.”

Chart courtesy of Idaho Department of Fish & Game.

Much of the debate about how to treat these steelhead turns on the effects of catch and release on wild fish survival and spawning. Because Idaho’s wild steelhead were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1997, the state must possess a permit in order to operate fisheries that will inevitably lead to some wild fish being incidentally caught and accidentally killed. But opinions vary widely on how much effect being caught and released has on a wild steelhead, although most everyone agrees that it does have some detrimental effects.

Idaho operates under the assumption that 3.2 percent of wild fish each year will die as a result of catch and release. This figure is based on research suggesting that 64 percent of returning wild fish will be caught and 5 percent of all steelhead that are caught and released will die. The 5 percent catch and release mortality rate is endorsed by NMFS and falls within 2-7 percent range found in most studies.

The wild fish groups dispute these numbers, especially the assumption that wild fish are caught at the same rate as hatchery fish. They point to several studies that suggest that stronger, more aggressive wild fish are more likely strike a fly or lure than hatchery fish. Aggression may be selected against in hatchery fish, since they are typically bred from parents who made it to the hatchery without being caught.

Both sides point to a study recently published in the scientific journal Fisheries Research on catch and release mortality in British Columbia’s Bulkley River. The study’s authors affirmed Idaho’s 5 percent mortality rate, but only in the short term. They tracked the fish for several months after being caught and found a 10 percent overwinter mortality and a 15 percent pre-spawn mortality. The baseline, what percentage of those fish would have died by those points if they hadn’t been caught is not well established, however.

Another element these researchers studied was the effects of air exposure on steelhead, another matter of contention in the Idaho debate. They found that increased air exposure can elevate the short-term physiological effects of being caught and released: “Findings suggest that steelhead anglers should limit air exposure to less than 10 [seconds], and that anglers should be cautious (minimize handling and air exposure) when water temperatures are warmer,” authors Will Twardek et al. wrote. Idaho has conducted its own studies regarding air exposure, on steelhead in the South Fork of the Clearwater and cutthroat trout in the South Fork of the Snake, and found negligible effects. The state insists that allowing anglers to hold up a steelhead is an integral part of the angling experience and the lasting memories it creates. One game warden said he would hate to see a kid get shamed for posing with his first steelhead just because he or she didn’t know any better.

None of this argumentation or animosity is likely to disappear soon. Idaho and the wild fish groups have reached a truce for now, but another confrontation is likely once NMFS issues a biological opinion on Idaho’s incidental take permit application. If that assessment from the federal government fails—in the opinion of the wild fish groups—to consider the best available science, the coalition may sue NMFS, which may lead to a temporary injunction and another closure.

There is a great deal of hope, however, that anglers of the Pacific Northwest can unite once again to address some of the larger, more detrimental factors affecting steelhead survival—like the four dams on the Lower Snake River.

“The only benefit to the brief steelhead season closure was the additional attention a struggling resource received,” said MeatEater Conservation Director Ryan Callaghan. “It’s a bitter pill to swallow, but if you are in the steelhead business the future is uncertain at best. When you hit folks in their wallets, they pay attention. My hope is that this stunt wakes people up to long term solutions. If it doesn’t, I’d hope these same groups sue around a long weekend when the economic impact really makes the phones ring.”

Feature image via of Josh Mills.