The Rev. Otha Durrett probably knew he’d done wrong six decades ago by claiming a 51-pound muskie he caught on another man’s unattended bank-pole. The Kentucky preacher just couldn’t admit such a sin once the rumors started and the bank-pole’s owner took him to court.

The fish’s rightful owner, Quentin Vance, 45, had baited his two bank-poles with 10-inch suckers on Feb. 18, 1965. Vance then anchored his two setups—one “a great big long pole about 12 to 15 feet long,” and the other “just a cut off” branch—into the west bank of the Little Barren River near its confluence with the Green River in Hart County, Kentucky.

Vance then went to his nearby home in Canmer but returned to the confluence at least once—around noon Feb. 20—to check his lines, leaders, hooks, and bait. While checking the suckers and verifying their good health, Vance saw a huge muskie surface. He could only hope it would hit one of his suckers.

Later that afternoon, the Rev. Durrett of Greensburg, stopped by Vance’s home, presumably for fishing advice. Vance and his family were reputable fishermen, and Vance was a serious muskie hunter known to share his expertise, even with visiting anglers. After talking with Vance, the preacher headed for the confluence.

The Rev. Durrett later claimed he checked Vance’s bank-poles and re-baited one of the hooks with a sucker he caught with his rod and reel. He said the fresh bait almost immediately triggered a strike. He then grabbed the bank-pole, and saw a muskie shoot 10 feet into the air.

The fish eventually broke the line when it “gave a flounce” in the shallows. The preacher claimed he then grappled bare-handed with the big muskie, and yelled to a nearby “colored man” for help. The men grabbed the fish under its gill plates and dragged it onto the riverbank. The muskie measured 52 inches in length, with a 27-inch girth.

Despite its immense size, the muskie apparently was never submitted as a possible Kentucky record, even though the state allows bank-poles—a pole and line with no reel—for such honors. The Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources states that fish submitted for record consideration must be caught “by rod and reel or on a pole and line.” Fish caught on trotlines, or by snagging, snaring, noodling, or bow-fishing are not eligible.

Sarah K. Terry of Mt. Sterling, Kentucky, holds the state’s hook-and-line record, a 47-pound muskellunge she caught in November 2008 on Cave Run Lake.

Catcher’s Remorse

After taking the muskie home to Greensburg, the Rev. Durrett soon felt remorseful, possibly because his neighbors were talking and spreading rumors after seeing a photo of him with the muskie in The Greensburg Record Herald. They didn’t think the fish was rightfully his and thought he should give it to Vance. One woman called the preacher and asked, “Don’t you know they’re telling around town that you’re accused of stealing a fish?”

Vance’s attorney, Glenn Davis Williams of Munfordville, later described public sentiment this way in a court appeal seeking the fish’s return: “There is a very strong custom or unwritten law on the Little Barren River and on Green River in this section of Kentucky that whoever takes a fish from his neighbor’s trotline or throwline will likely get a charge of buckshot in his behind if he gets caught in the act. That probably accounts for the fact the appellant’s (the Rev. Durrett) conscience hurt him considerably.”

Vance’s attorney wasn’t speculating about the preacher’s conscience. On Feb. 23, three days after landing the muskie, the Rev. Durrett returned to Vance’s home at about 6:30 a.m. to pray before him and beg forgiveness for claiming the fish and taking it home. After crying and offering a “loud and eloquent prayer,” the preacher told Vance the Lord had messaged him and would forgive him if he gave Vance the fish.

The preacher’s companion during that visit, a man named Garland Brewer, later testified that the Rev. Durrett conceded the muskie was Vance’s fish and that it was his “duty to get the fish and bring it back to you right here.”

No Pity Granted

Perhaps the preacher did all that praying and crying in hopes Vance would take pity and let him keep the fish. When that didn’t happen, the preacher drove off, presumably to get the fish. But he returned in 15 minutes to ask Vance how much money he wanted for the fish. Vance reminded him that it’s illegal to sell a game fish, and that he wouldn’t be satisfied until the Rev. Durrett brought him the fish.

The preacher told Vance he’d taken the muskie to a taxidermist in Louisville, 75 miles north. Vance offered to drive there himself to retrieve the fish or pay the taxidermist to mount it. The preacher declined, saying his son had taken the fish to the taxidermist and didn’t know the location. He also told Vance he “didn’t want to put him out” of any time or expense and said, “I got you in enough trouble already.”

Vance said the preacher finally agreed to bring him the muskie at his preferred time and place. But he never did, even though he had secured Vance’s forgiveness by crying and praying. Instead, he later testified he never agreed to return the fish and had simply visited Vance to help him and ensure his “eternal welfare.”

Either way, Vance’s attorney filed a lawsuit in March 1965 seeking $6,000; $400 as the sales value of a trophy muskie mount, and $5,600 for the “unlawful taking and detaining of the fish.” Vance said the Rev. Durrett’s actions cost him endorsement deals on boats, outboard motors, fishing tackle, and other gear.

The lawsuit also ridiculed the preacher for breaking his promise to surrender the muskie in return for divine forgiveness, noting: “After leaving the plaintiff’s home on Feb. 23, the defendant received a different message from another kingdom, because he never returned the fish.”

And so began a nine-year battle in three Kentucky courts over one of the biggest muskies ever seen or caught in the commonwealth. The Rev. Durrett’s attorney, Morris Butler, tried to get the case dismissed that spring. Butler disputed everything in Vance’s complaint and insisted his client was entitled to the fish because he caught it. The court rejected the preacher’s motion to dismiss and scheduled the case for trial in January 1966.

A Quick Verdict

As the January 1966 trial date neared, newspapers across Kentucky and Tennessee started covering the case, as did Nashville TV stations. Spectators crammed the Hart Circuit Courtroom on Jan. 12, 1966, to witness the trial.

When called to testify, the Rev. Durrett claimed he visited Vance’s home three days after catching the muskie to quiet rumors that he stole the fish. He said he kept the fish because he thought it was rightfully his, and visited Vance to ask why he was telling people the fish was stolen. The preacher’s attorney claimed he told Vance, “When I get ready to leave for up yonder, I don’t want any fish standing between us.”

He denied praying at Vance’s home but “did some” (praying) before arriving. He also denied saying he would bring the fish to Vance because Vance was angry and unreasonable during their exchange. “He was raring and charging and cursing, being offensive to me and saying everything he could think of,” the preacher testified. “I said I felt I ought to reason with him because I am a Christian, and I try to treat everybody right, and that I ought to go back and try to reason with the man.”

When asked about returning the second time on Feb. 23 to offer money and/or to retrieve the fish from the taxidermist, the Rev. Durrett said he had simply felt frustrated. He said Vance was angry, and he only offered money because Vance was so unreasonable. “I couldn’t even talk to him for all the raging, and swearing and cursing that he was doing to me … and didn’t give me much time to talk. He went in the house and said, ‘I’m going to sue you.’”

But the preacher’s companion that day, Garland Brewer, didn’t remember the encounters that way. When Brewer testified, he said he “never heard a word” of curses, insults, or abusive language from Vance.

After hearing Vance’s accusations and the preacher’s answers, the nine-man, three-woman jury needed only an hour to rule for Vance. The jury also fined the Rev. Durrett $750 for taking the muskie.

National Headlines

Newspapers across the country printed the United Press International’s account. The article showed up in major dailies like The Miami Herald, Pittsburg Press, Albuquerque Journal, Salt Lake Tribune, and Press-Telegram in Long Beach, California. Not surprisingly, the newspapers’ headline writers had fun with the unusual story.

The Chicago Tribune’s headline shouted, “Take $750 Bite Out of Fish Thief.” The article beneath reported: “The Rev. Otha Durrett was hooked today for $750 for putting the bite on another man’s fish.”

The Times Colonist newspaper in British Columbia declared, “Preacher Pays: Jury Hooked by Fish Tale.”

The Los Angeles Evening Citizen-News claimed, “The jury went for the story, hook, line and sinker.”

And The Pittsburgh Press reported: “Anglers note: The moment of truth is when a fish takes the bait—not when it is landed. That was the decision of a Hart County jury yesterday in the case of a record-size muskie.”

The Rev. Durrett felt wronged and appealed, saying the case should have been tried in Green County, where he lived; not Hart County, where Vance lived. The appeals court eventually agreed. Anticipating that decision, Vance’s attorney filed an action in Green County. “The fish case,” however, languished in Green County courts for years. Vance eventually tired of the mess and dropped the case, letting the preacher keep the muskie.

Litigating for Sport & Justice

Maryglenn Warnock of Nashville thinks Vance simply lost interest and didn’t give up because of legal fees. Warnock should know. For one, she’s a serious muskie angler who cranks bucktails and rips jerkbaits across muskie waters from Tennessee to northwestern Ontario each year.

Plus, Warnock is the maternal granddaughter of the attorney who handled Vance’s case all nine years: Glenn Davis Williams. In fact, Warnock’s parents so admired Glenn Davis Williams that they named her after him: Maryglenn.

Warnock assumes she inherited her love for fishing and muskies from her grandfather, too. She said he started fishing for muskies in the 1930s and often targeted them on the Green River with his father-in-law, Warnock’s great-grandfather.

“My grandfather didn’t handle ‘the fish case’ for money,” Warnock told MeatEater. “He did it for sport. He exposed a theft and had a good time doing it. He wanted to do what was right. He thought taking another man’s muskie was abhorrent. No other case delighted him more, and he handled a lot of cases during his career. I mean, who wouldn’t enjoy a court battle over a muskie that involves a preacher, a big fish, 10-inch suckers, and two lawyers who were avid sportsmen?”

Warnock recalled hearing bits and pieces about the case while growing up in the 1970s and ’80s, even though Vance dropped his lawsuit when she was a preschooler. Still, she didn’t appreciate the story’s depth until decades later when she better understood fishing, local culture, fishing etiquette, and other social norms.

“There was a lot more going on in that dispute than any kid could know, or a court transcript could show,” Warnock said. “That Vance fellow was an avid muskie fisherman. He knew where a big fish was hanging out, and he knew its habits. And then this stranger showed up at his house, asked his advice on where to fish, and just happened to be there when the muskie hooked itself on Vance’s bank-pole.”

“The preacher had no real experience on that river, and none at all with muskies, and yet he claimed Vance’s fish as his own,” Warnock continued. “I get the temptation. If I saw a 52-inch muskie, I’d want it, too. But even after the guy’s neighbors learned the truth about that fish, and a jury ruled the muskie didn’t belong to him, the preacher still wouldn’t let it go. He really wanted the fame and notoriety that comes with big muskies.”

Case No. 83912

Warnock became fascinated with the case five years ago, about the time she realized no fish mattered more to her than the muskellunge. She learned all she could about the purloined muskie through old newspaper articles and other folks’ memories. When that didn’t fully explain things, Warnock’s personal attorney—her husband, Tim Warnock—went to work. In January 2021, he brought home a spiral-bound notebook labeled, “CASE NUMBER: 83912.” The binder was crammed with 250 pages of court records detailing “The Fish Case.”

As Warnock studied the files and testimony, she recognized the many charms, customs, rivalries, and jealousies she knew from her own childhood. For instance, the court records included testimony that cast doubt on the Rev. Durrett’s honesty and integrity. Vance testified that the Rev. Durrett had lied repeatedly about how he caught the fish, including that he caught it on a rod and reel.

Eventually, however, he “owned up” to catching the fish on Vance’s bank-pole. Vance said those deceptions meshed with what he already knew about the preacher.

“I had heard of him all my life but wasn’t personally acquainted with him before this,” Vance said in a September 1965 deposition. “I heard he wouldn’t tell the truth. That’s what other people say.”

Warnock said her grandfather shared a similar distrust of some preachers from his era. “He said they were ‘Sunday go-to-meetings sons-of-bitches,’” she said. “He considered the fish case an act of theft, in keeping with that preacher’s reputation. My father shared that distrust. When he saw certain preachers I won’t name, he’d say, ‘Keep a firm hand on your wallet.’”

She also wasn’t surprised the case went nowhere once it left the Hart Circuit Court and ended up in Green County. “Rivalries and distrust between counties were common back then and still exist today,” Warnock said. “You didn’t trust ‘those people’ over there, and they didn’t trust you. If you wanted justice from the county next door, it didn’t come quickly or easily.”

Museum Mount

What became of the muskie itself? As the Rev. Durrett requested, the Louisville taxidermist created a skin mount of it. Warnock said the mount eventually fell into disrepair, but one of the preacher’s relatives got it restored.

Warnock thinks the mount then ended up with a retired game warden for a few years, and perhaps spent time in his garage before finding a home in the Green County Museum in Greensburg, Kentucky. Bill Landrum, the museum’s curator, confirmed the mount remains on display today.

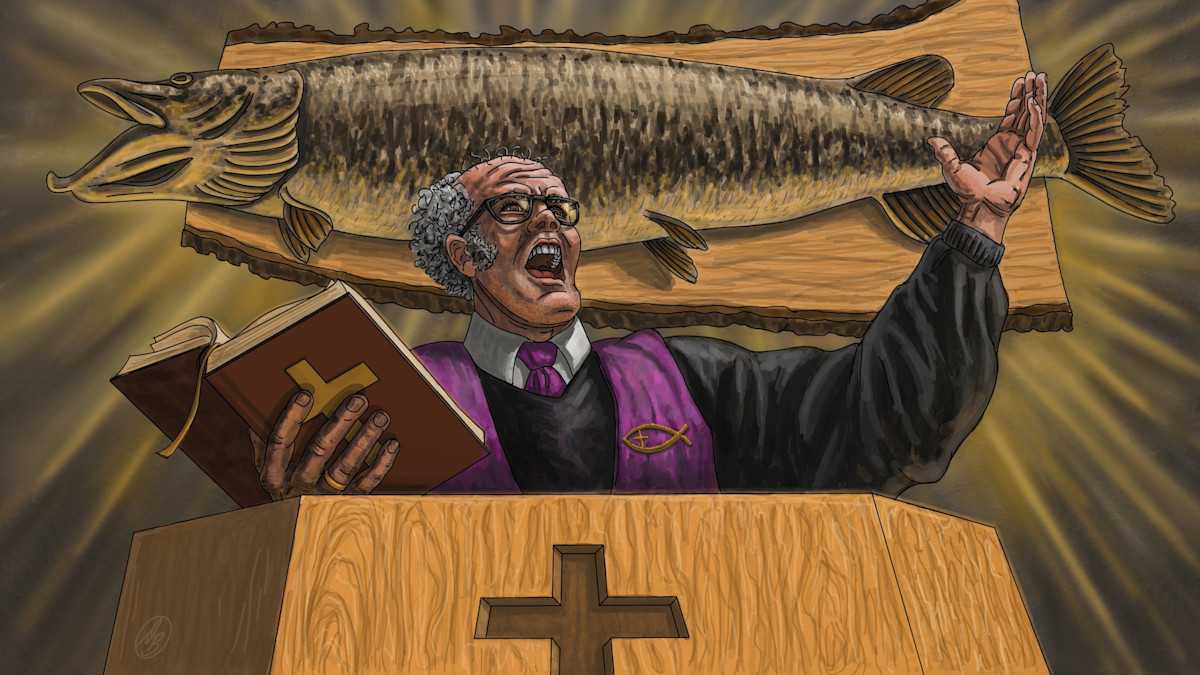

Feature art by David Burgess.