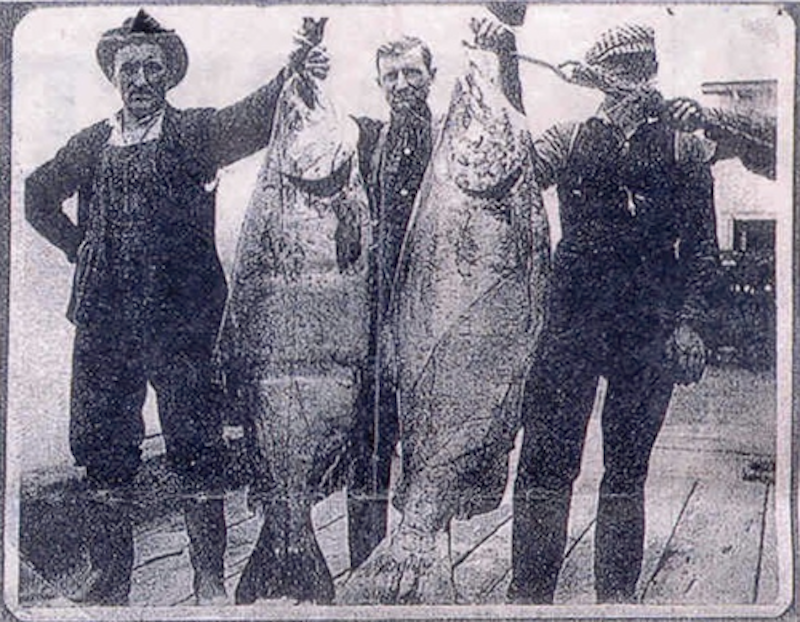

With rhythmic kicks of their huge tails, the salmon propelled themselves up the 40-foot-high Celilo falls—60-pounders, 70-pounders, 100-pounders. Tribal fishermen, standing on platforms built over the falls, scooped the fish from the water with dipnets (and spears by some accounts), using momentum to fling fish onto the banks or platforms. The frothing currents threw a dense spray over the whole area. The wood terraces were slippery and wet—sometimes fishermen fell in the churning waters. Venturing onto the platforms was a right of passage for young men.

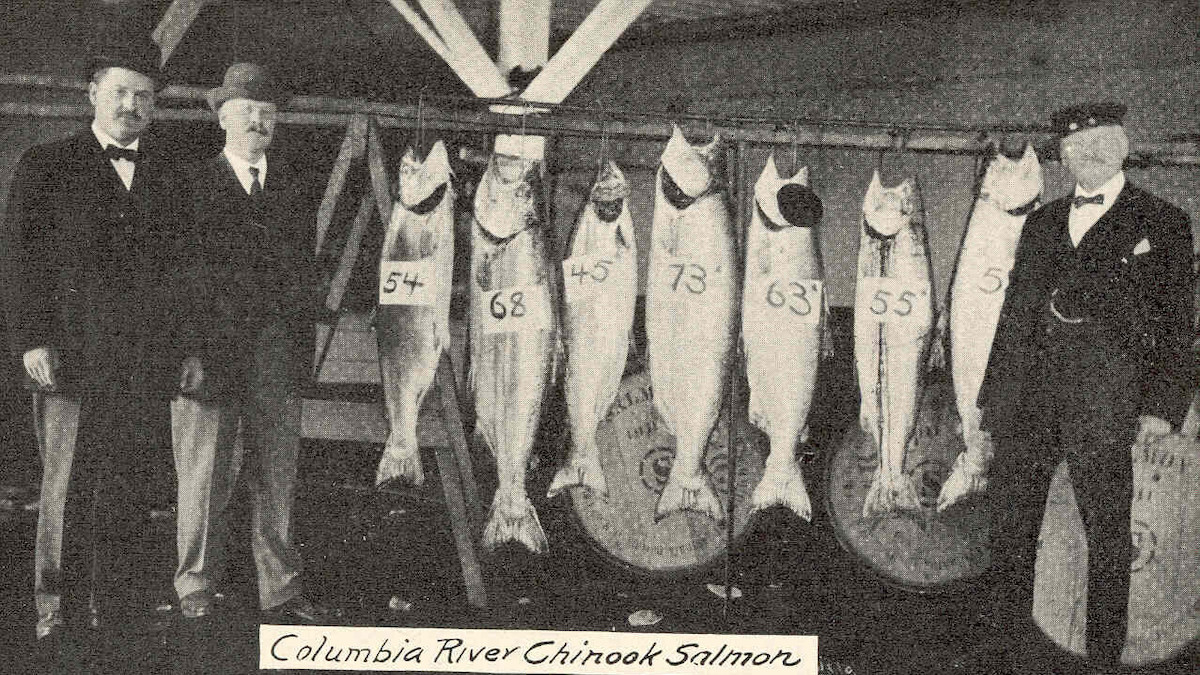

For a few months every summer, it was chaos as Chinook salmon made their summer spawning pilgrimage up the Columbia River, slicing deep into the heart of the Pacific Northwest—Washington, Oregon, Idaho, even central British Columbia. These gargantuan fish became colloquially known as the “June Hogs,” and their annual return brought swarms of tribal and commercial fishermen to the banks of the river every June and July.

A few miles below the falls, where fish were still chrome-bright and fresh from the Pacific Ocean, fish wheels lined the banks. These watermill-type structures plucked fish directly from the river. Additionally, 1,700 commercial gillnet boats—sailboats—made sweeping sets in the river.

Nearby canneries operated at full capacity, 24 hours a day, pumping out pallet upon pallet of cans for shipment across the country. In the average year, the canneries kicked out about 30 million pounds of fish.

Meat care was non-existent in these factories. Historical photos taken around the turn of the century (late 1800s to early 1900s, that is) depict workers standing waist-deep in piles of king salmon. In other photos, the fish are stacked nearly to the rafters, stewing in the often 90-degree summer heat.

At the industry’s peak in the 1880s, there were 39 canneries operating near the mouth of the Columbia. Four brothers—the Hume brothers—owned the bulk of them. To lower production costs, they brought in Chinese laborers from overseas to work in the factories. And there was no lack of a market, either. The industry continued full-steam-ahead through World War I, fueled by a demand for non-perishable goods.

But like all big resource booms in the west—gold, copper, oil—the free-for-all didn’t continue for long. David Montgomery, a fluvial geomorphologist and author of King of Fish (a good resource, should you desire more on the subject), highlights the statement of historian Hubert Bancroft in 1888: “Nature does not provide against such greed, and it is doubtful if art can do it. The Government, either state or general, should assume control of this industry by licensing a certain number of canneries, of given capacity… otherwise there is a prospect that the salmon, like the buffalo, may become extinct.”

As it turns out, Bancroft’s pessimistic prediction wasn’t far from reality. By the 1960s, the June Hogs were long gone, and salmon returns were a fraction of their former glory.

The Columbia Today

The scene at Celilo Falls is far less dramatic today. The cascades are now submerged under Lake Celilo, a reservoir impounded by the Dalles dam in 1957. On a June or July day, it’s hot, dry, and noisy, but not from the sound of rushing water. Truckers and freight trains barrel past the reservoir, likely with no idea of the falls or history that lies beneath the stagnant waters.

The canneries are gone, too. The last major factory boarded up its windows in 1980, with most shutting down decades earlier. There simply weren’t enough fish to make the endeavor profitable.

But the demise of the June Hogs can be traced back further than the Dalles. In 1942, Grand Coulee Dam in north-central Washington impounded the Columbia for the first time. The 350-foot-tall dam was built without fish passage, blocking access to thousands of miles of the best spawning grounds in the Columbia basin.

The dam itself was built to accommodate the growing demands of a country at war. The reservoir it created (Lake Roosevelt) provided irrigation for nearly 700,000 acres of farmland, and a hydroelectric plant powered aluminum factories (for fighter plane fuselages), textile plants, and plutonium enrichment operations at the Hanford site in eastern Washington (for use in the production of nuclear weapons).

To mitigate the impacts of Grand Coulee, the U.S. Congress funded three salmon hatcheries below the dam, which collectively pump millions of juvenile fish into the river annually (still to this day). Only a fraction of them—less than 1%—ever return as adults. The Leavenworth Hatchery alone, for example, releases 1.2 million fish annually, and in 2021 received 3,300 adult fish in return.

But dams aren’t the only reason the June Hogs disappeared. Montgomery emphasizes what he calls “The Five H's”: harvest, hydropower, habitat, hatcheries, and a failure to learn from history. Together, these factors led to the slow decline, as each took a bite of the salmon run. Competing interests such as logging, mining, ranching, and agriculture have time and again superseded salmon in terms of habitat usage and water quality in the Pacific Northwest. It’s the same story that played out on the East Coast with Atlantic salmon a century earlier and on the other side of the pond in England and Scandinavia even a century before that. History repeats, and the trajectory of salmon runs in the Columbia Basin appears to be no exception.

Today, the average Columbia Chinook is between 10 and 20 pounds—a far cry from the five-foot, 100-pound fish from the days of yore. And the overall run size to the entire Columbia basin? Around 175,000 fish—a shadow of the former 10 to 15 million. But on any given summer day, anglers continue to ply the waters of Oregon and Washington, hoping one of the last remaining descendants of the June Hogs might turn up on their lines.

Feature image via OSU Special Collections & Archives.