This is Part Two of a two-part series on the 1971 murder of Warden Neil LaFave. Part One covers how Brian Hussong decapitated LaFave and the historic investigation for his murder weapon. Part Two covers Hussong’s daring escape from prison and his 12 weeks spent hiding in the forest.

Wisconsin conservation warden Dale Morey slept with his loaded .38-caliber handgun beneath his pillow for three and a half months after the killer he helped convict escaped prison in August 1981.

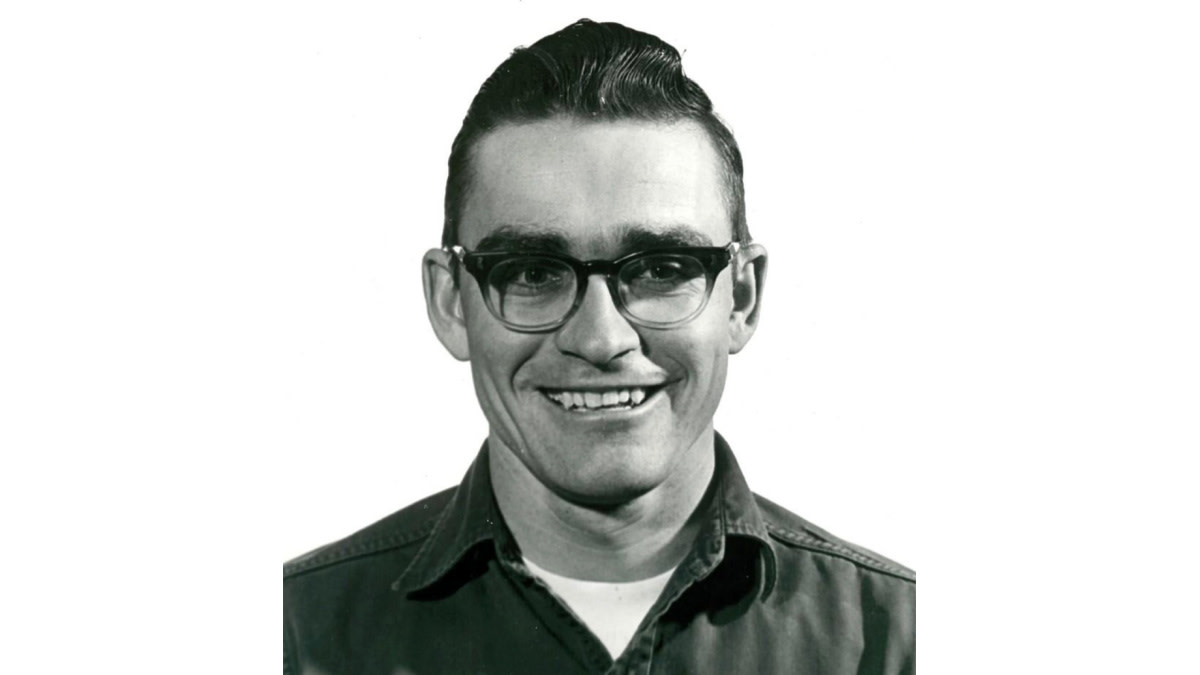

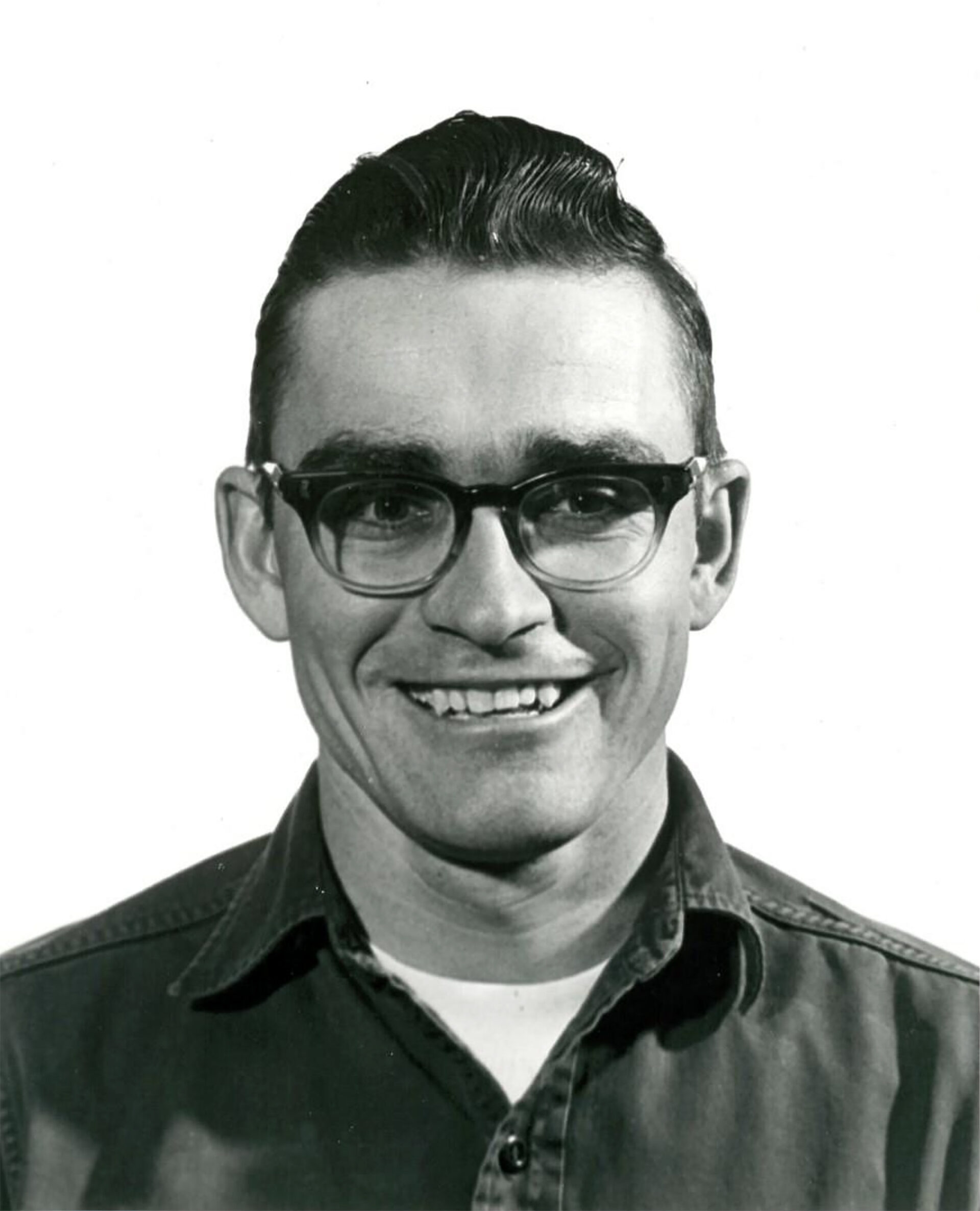

Anyone who knew of Brian Hussong and how he brutally murdered Neil LaFave, 32, a decade earlier knew Morey wasn’t overreacting. Hussong was 21 when he killed LaFave, a Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources wildlife technician and conservation warden. Hussong shot LaFave repeatedly in the face with a .22 rifle on Sept. 24, 1971, then decapitated him with multiple .30-06 blasts and a shovel blade. He buried LaFave’s head and body nearby in separate, shallow graves inside the Sensiba Wildlife Area northwest of Green Bay.

In fact, everyone who helped investigate, prosecute, and imprison Hussong in 1971-72 took precautions after Hussong escaped and disappeared for 104 days. Donald Zuidmulder—the district attorney who prosecuted Hussong—sent his wife and children from their Green Bay home to the family’s cottage 40 miles northeast in Door County.

Peter Peshek, an assistant attorney general who coordinated the wiretap that incriminated Hussong, gave his wife and four children specific instructions: Call 911 and hide in one room if they hear anything suspicious during his absence. While Peshek worked 90 miles away in Milwaukee one night, his wife heard strange sounds in their basement. After police arrived and searched the home, they assured her the sounds were just the Pesheks’ newborn Labrador puppies.

Morey repeated similar advice to his wife, rekindling memories of someone combing through their garbage cans during the 12-week Hussong investigation in autumn 1971. The incident was so suspicious that Morey trained his wife to load, handle, and shoot a handgun. Mary Morey took the lessons seriously. Morey felt confident his training and her maternal instincts would protect her and their five kids when he wasn’t home.

Promised Vengeance

Besides being a brutal killer, Hussong vowed revenge on everyone from jurors to witnesses. Morey led the investigation with Sgt. Marvin Gerlikovski of the Brown County Sheriff’s Department. After a Brown County jury convicted Hussong in April 1972, Morey and Gerlikovski briskly escorted Hussong from the courtroom. As they passed the district attorney, Hussong glared back at Zuidmulder and hissed, “I’ll kill you, you little son of a bitch.”

The investigators hurried Hussong outside and into the back seat of a police car, flanking him as the driver took them to the Wisconsin State Reformatory, a maximum-security prison now called the Green Bay Correctional Institution. During the ride, Morey asked Hussong, “Why did you do it?”

Hussong sat silently, much as he did throughout the investigation, prosecution, and trial. Instead of answering Morey, Hussong said icily: “If I ever get out, what happened to Neil LaFave will look like child’s play compared to what I’ll do to you.”

Hussong kept making threats when talking to fellow inmates. Morey said the killer’s behavior apparently improved, however, after he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and medicated.

“The guards said he became a model prisoner,” said Morey, now 86. “They even asked, ‘Are you sure you got the right guy? This guy is no problem at all.’ He was taking his medication, working out, building himself up, and reading books on survival. He had been a weird, skinny, gangly guy, but transformed himself into a physical specimen. He was probably planning and preparing for an escape the whole time.”

Hussong transferred in July 1979 to the Waupun Correctional Institution, another maximum-security penitentiary. He then transferred to the Fox Lake Correctional Institution, a medium-security prison, in November 1980, roughly nine months before his escape.

Fox Lake’s superintendent, John Gagnon, told the Green Bay Press-Gazette in August 1981 that Hussong had a good prison record and could have applied for parole in 1983. Gagnon said it was normal to transfer prisoners with good records to lower-security facilities as they approach parole eligibility.

The Great Escape

Instead, Hussong coordinated his escape during visits from Mary Conrad, 32, a Sheboygan woman who regularly wrote to and visited him in prison. Morey didn’t recall the details of their relationship, but psychiatrists call this “prison bride” syndrome “hybristophilia.” It usually produces strong desires for those who have committed horrible crimes.

Conrad visited Hussong the day he escaped, Aug. 28, 1981. In his book “Protectors of the Outdoors,” retired Wisconsin conservation warden Jim Chizek wrote that Hussong and Conrad used that afternoon visit to fine-tune their plan. After leaving, Conrad threw a bolt-cutting tool over a prison fence where buildings blocked the guards’ view. Hussong escaped soon after dark, about 8 p.m., by cutting through two chain-link fences. The prison reported him missing at its 9 p.m. inmate check.

Conrad waited nearby in her car. She had shut off its headlights while approaching and used the emergency brake to avoid activating the taillights. She also removed the dome light so Hussong could enter the car unseen.

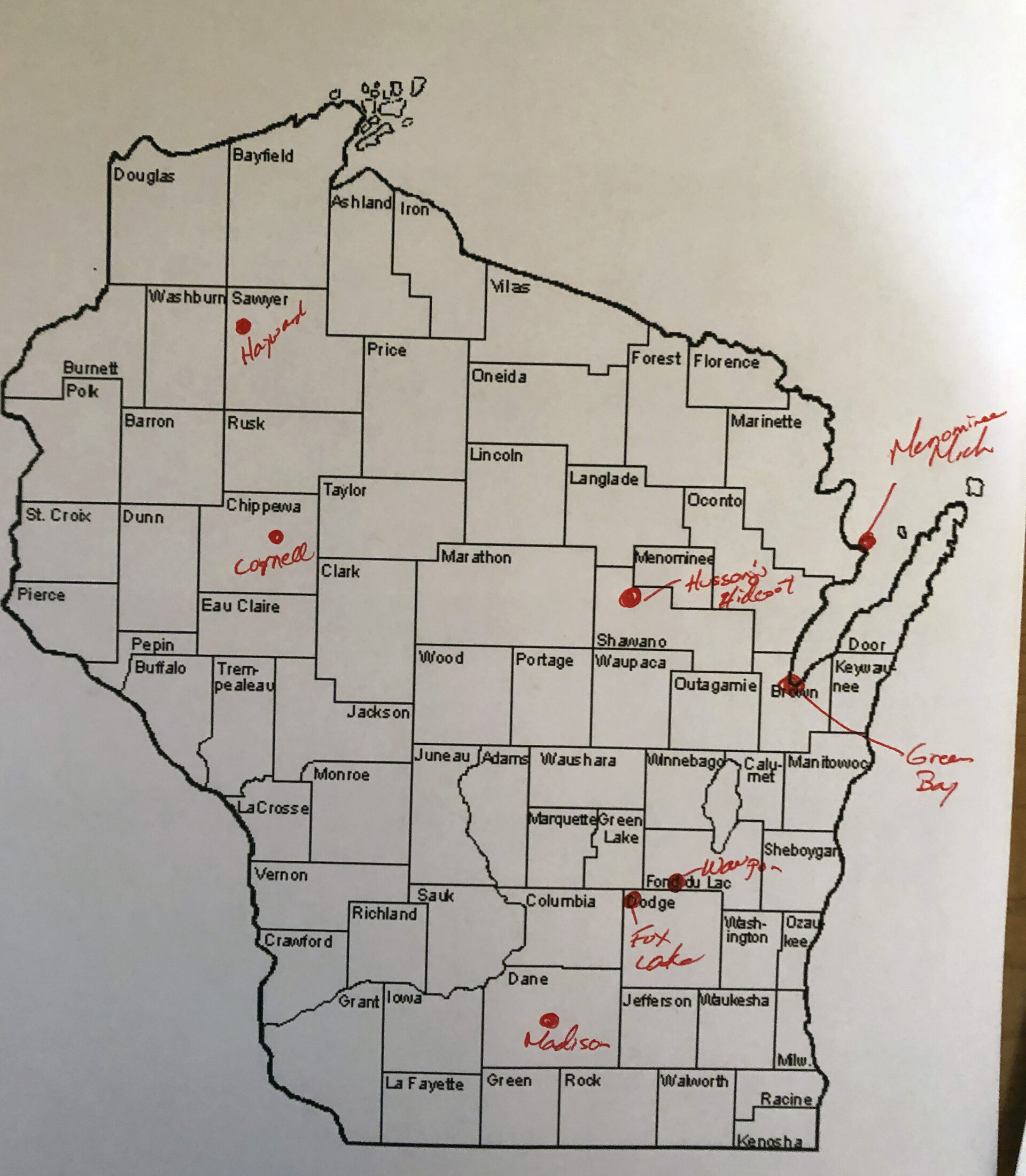

Morey said police and sheriff’s deputies quickly warned everyone connected to the Hussong case. “Sheriff’s deputies were patrolling my home within an hour,” Morey said. “No one knew where he went those first two days, and later there were all kinds of ‘sightings’ reported in Madison, Minocqua, Green Bay, and Menominee, Michigan, but nothing came of those.”

On Aug. 30, two nights after the escape, an off-duty policeman 365 miles northwest of the southern Wisconsin prison spotted a car driving erratically as it neared Hayward, Wisconsin. The cop assumed the driver was drunk, and radioed the car’s description to on-duty officers. They learned it was registered to a Sheboygan woman, so they had no idea an escaped killer who hadn’t driven in a decade was behind the wheel. Three officers in two squad cars rushed to the intersection of highways 27 and 63 in Hayward to await the suspected drunk.

When the car stopped for a light at the intersection, the two officers in the nearest squad car saw the driver reach under the seat. They thought he was hiding alcohol, so when the light turned green they activated their lights and pulled him over. The driver, Hussong, had actually grabbed a .44-caliber snub-nosed handgun from beneath the seat when he saw the police cars.

Hussong stepped from the car and met one of the approaching officers as the other cruiser stopped in front of Conrad’s car. When the officer requested his driver’s license, Hussong said it was in the vehicle and turned as if going to retrieve it. Instead, he spun and punched the policeman in the face.

Fighting and Fleeing

The stunned officer recovered and shoved Hussong hard into Conrad’s car. Hussong scrambled back behind the wheel as the other officer struck him in the shoulder with his flashlight. Hussong put the car into reverse and punched the gas pedal, running over the second officer’s foot, breaking it. He then put the car into drive and accelerated, only to slam into the second squad car as another officer pulled out to box him in.

The cars’ bumpers locked in a shower of sparks, but Hussong kept accelerating, breaking free and then racing through town before fleeing east on Highway 77. A State Patrol officer and a local dispatcher, however, quickly set up a roadblock a mile and half away at Airport Road. Rather than try crashing through the two squad cars, Hussong jammed on the brakes, leaped out, and ran into the woods, leaving Conrad behind.

Police questioned Conrad that night, but she didn’t cooperate. She gave her name as Linda Vieau, and told police she had picked up Hussong as he hitchhiked about 15 miles south of Hayward. After finding two knives and a receipt for a .44 handgun in Conrad’s purse, they alerted searchers that the suspect was armed. The next morning, after learning Conrad’s true identity and verifying details with the Fox Lake prison, the law-enforcement agencies realized they were hunting Hussong, the convicted murderer.

At 2 a.m. on Aug. 31, the State Patrol officer who helped block Hussong’s escape on Highway 77 spotted a car 4 miles east of town that had just been reported stolen. When he pursued it down County Highway K, the driver suddenly stopped, got out, and fled into the forest near the Lac Court Oreilles Indian Reservation.

A sheriff coordinating the manhunt asked two conservation wardens, Bill Hoyt and Jim Flanigan, to search a nearby logging area. Hoyt and Flanigan found intermittent footprints in the dirt, slash, and debris, and followed the prints’ general direction to a large brush pile. The wardens searched opposite sides of the piled brush, occasionally poking into it with sticks. After finding nothing more they returned to their truck and reported the dead end.

About a day later and 30 miles to the southeast, Hussong stole a pickup truck. Authorities found the truck abandoned two days later 50 miles south in Cornell, Wisconsin. There he stole an Oldsmobile, which police found abandoned in mid-September 190 miles east in Menominee, Michigan, roughly 45 miles north of where Hussong killed LaFave.

Zeroing In

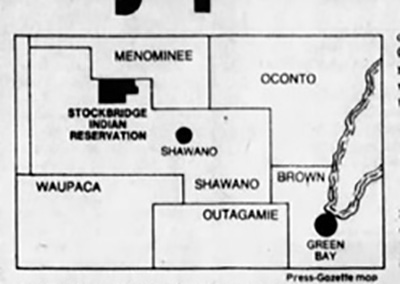

Hussong’s trail went cold for a few weeks, but police stayed busy throughout October and November investigating rumors that Hussong was hunkered down in the forests of northwestern Shawano County. Investigators soon learned Hussong had served time with two brothers whose father owned land there on the Stockbridge-Munsee Indian Reservation, about 80 miles southwest of Menominee and 55 miles northwest of Green Bay.

Morey said police zeroed in on Hussong’s hideout in early December 1981 after a pulpwood dealer cruising the forest reported being confronted by a man who fired a handgun round into the ground between his feet. One of the brothers warned the pulpwood dealer to be careful because “that’s the guy who killed the game warden,” Morey said.

“Hussong had been off his meds a few months by then, and was probably losing control again,” Morey said.

Police learned Hussong had contacted one of the brothers, who rented him land about 1.5 miles from the nearest road. Hussong built a 12-foot-square shack from cardboard and cedar poles, which wardens pinpointed from an airplane. On Dec. 8 and 9—after assembling 50 law enforcement officers from seven agencies—Shawano County Sheriff James Knope organized eight teams and detailed their roles for capturing Hussong on Thursday, Dec. 10.

At 5 a.m. on Thursday, the teams split up to set roadblocks and semi-circular perimeters starting about 100 yards northeast of Hussong’s shack. Warden Winter Hess, a Vietnam War veteran in charge of setting the perimeters, radioed at 6:45 a.m. that his teams were in place. By then another team finished searching nearby summer cottages to verify Hussong wasn’t using them.

At 7 a.m., Knope and five other officers executed a search warrant on the brother suspected of helping Hussong. The brother confirmed he knew Hussong and the shack’s location, and let them search his nearby buildings. He also agreed to show them how to approach Hussong’s shack unseen from the south. The brother led four teams—including Knope and Garner Oswald, a Department of Corrections officer—down a two-track road to a spot where they could park out of view from the shack.

The Confrontation

The officers advanced about 150 yards until seeing Hussong’s shack in the distance. Oswald used a bullhorn to order Hussong to surrender. Nothing happened. It appeared Hussong hadn’t heard the bullhorn, so Knope directed two teams to fan out into a skirmish line and slowly advance. Minutes later, Shawano city police officer Don Schoenhofen paused, leaned his 12-gauge shotgun against a cedar tree, and unzipped his insulated snowmobile suit to relieve himself. As he urinated, he heard footsteps and saw boots moving nearby beneath deer-browsed cedars.

Schoenhofen recognized Hussong when he stepped out 10 yards away, cradling a rifle in one arm and holding a milk jug with his other hand. Schoenhofen stood paralyzed and helpless, his shotgun beyond reach.

Hussong, however, mistook Schoenhofen for someone he knew, and didn’t see his police uniform beneath the snowmobile suit. Describing the incident in “Protectors of the Outdoors,” Chizek wrote that Hussong asked the officer, “How’s the hunting, Dave?”

Schoenfeld played along: “Not too good. Getting cold. Going to get out of here.”

Hussong turned toward a nearby creek, filled the jug, and returned to his shack. A nearby officer approached Schoenfeld and briefly discussed the harrowing encounter. They moved forward a few feet, and laid down after spotting Hussong’s shack through the cedars.

Nearby, Oswald and three officers sneaked behind a woodpile near the shack. They saw Hussong inside the door, wearing blue jeans and an old hunting shirt.

It was 8:20 a.m. Oswald lifted the bullhorn again and ordered Hussong to surrender. Instead, Hussong stepped inside, grabbed a rifle—a .30-06 later traced to a hardware store theft—and fled the opposite direction. He had told inmates and others he would never again be arrested. The officers shouted for him to stop, but he suddenly turned after a few yards and aimed his rifle at them.

They instantly opened fire with handguns, .223 and .308 rifles. Hussong fell but rolled and pointed his rifle at Oswald, who shot him with a 12-gauge load of double-ought buckshot. Hussong died soon after in an ambulance, and was pronounced dead-on-arrival at the Shawano Hospital.

“[Hussong] never fired a shot, but his rifle was off safety,” Morey said. “They had no choice but to shoot when he aimed at them. Maybe it was suicide by cop, but we’ll never know for sure.”

Knope told the Green Bay Press-Gazette that Hussong was hit in the face, hands, neck, and upper chest. When police searched his shack, they found knives, a Remington 870 12-gauge shotgun, a large ammo supply, and a partially eaten sandwich he’d made for breakfast. Outside they found a half-eaten deer hung in a tree and a skinned squirrel stuck on a tree spike. It appeared Hussong was preparing to spend all winter in the primitive shack.

Aftermath

Mary Conrad, the woman who helped Hussong escape prison, was convicted in October 1981 for aiding and abetting Hussong, and served two years in prison. Authorities didn’t charge the former inmate who helped Hussong hide in Shawano County’s big woods.

During investigations after Hussong’s death, authorities also learned he intended to kill wardens Hoyt and Flanigan as they searched the large brush pile east of Hayward on Aug. 31, 1981. Hussong told his Shawano County accomplice that he was hiding in the brush pile, and aimed his .44 handgun at one of the wardens but didn’t shoot, fearing the other would get the next shot. He said the wardens never stayed together long enough to give him the edge, keeping mostly to opposite sides of the pile.

After hearing Hussong was dead, members of the jury that convicted Hussong relaxed for the first time in nearly 15 weeks. Lois Mellen, whose husband, Richard J. Mellen, served as foreman, told the Press-Gazette that Hussong had vowed to kill every one of them. “After he escaped, my husband said he didn’t want to let it bother him, but it did,” she said.

Not far away, Zuidmulder’s wife and kids returned to their Green Bay home after their three-and-a-half month absence. And, 180 miles to the southwest where he lived while working in Madison at the DNR’s central office, Morey returned his handgun to the secure locker in his home.

“I don’t think Hussong ever came looking for anyone, but we sure didn’t know that at the time,” Morey said. “That’s the longest I’ve ever looked over my shoulder.”

Click here to read The Savage Murder of Warden Neil LaFave, Part One.