People seeking Keith Cormican’s expertise know they’ll never again see their loved one alive. They’ve realized their child, spouse, sibling, or parent has drowned, and that local search-and-rescue teams must abandon the search and return to more pressing duties.

But families need answers, and they want to bury their dead. So they call Cormican, often begging for his help. Lest there be any mistake, Cormican’s boat states his somber mission: “Search and Recovery.” The time for “rescue” is long past.

Since opening his nonprofit operation, Bruce’s Legacy, in 2013, Cormican has recovered 31 drowning victims down to 250 feet deep and up to 16 years after they sank into bays, lakes, and reservoirs. He mostly answers calls from within the United States, but he’s traveled as far as Nepal to recover a boy from a lake up a mountain at 18,000 feet elevation, not far from Mount Everest.

Cormican, 60, of Black River Falls, Wisconsin, created Bruce’s Legacy to honor his older brother, a firefighter who drowned in August 1995 at age 40. Bruce died while searching for a man who drowned two days earlier while canoeing with his daughters. The girls survived, but Bruce Cormican and two other firefighters didn’t want the family to have to wait for the father’s body to surface. Their efforts turned tragic when rushing waters swept the firefighters off their feet and into a whirlpool. The other two firefighters survived.

Unique Skill Set

Besides running Bruce’s Legacy, Keith Cormican teaches search-and-recovery classes around the country to first responders and law enforcement dive teams. As a longtime diver, search-and-recovery expert, and salesman for Klein Marine System’s side-scan sonar equipment, Cormican is a uniquely skilled instructor.

Even so, few recoveries are easy, and some fail. No matter the outcome, Cormican gives every mission his best shot. In July 2018, for example, he located the body of Tyler Spink, 22 months after the Michigan kayaker disappeared in rough waters on Lake Michigan. Cormican made four trips to Michigan and combed 6 square miles over 23 days before finding Spink’s body tight to a log 180 feet underwater.

Cormican doesn’t charge for his search-and-recovery services; only the food, lodging, and travel expenses for him and his volunteers. He said families desperate with grief are too vulnerable to thinking “money is no object.”

“I can’t take advantage of their situation,” he said. “It wouldn’t be right.”

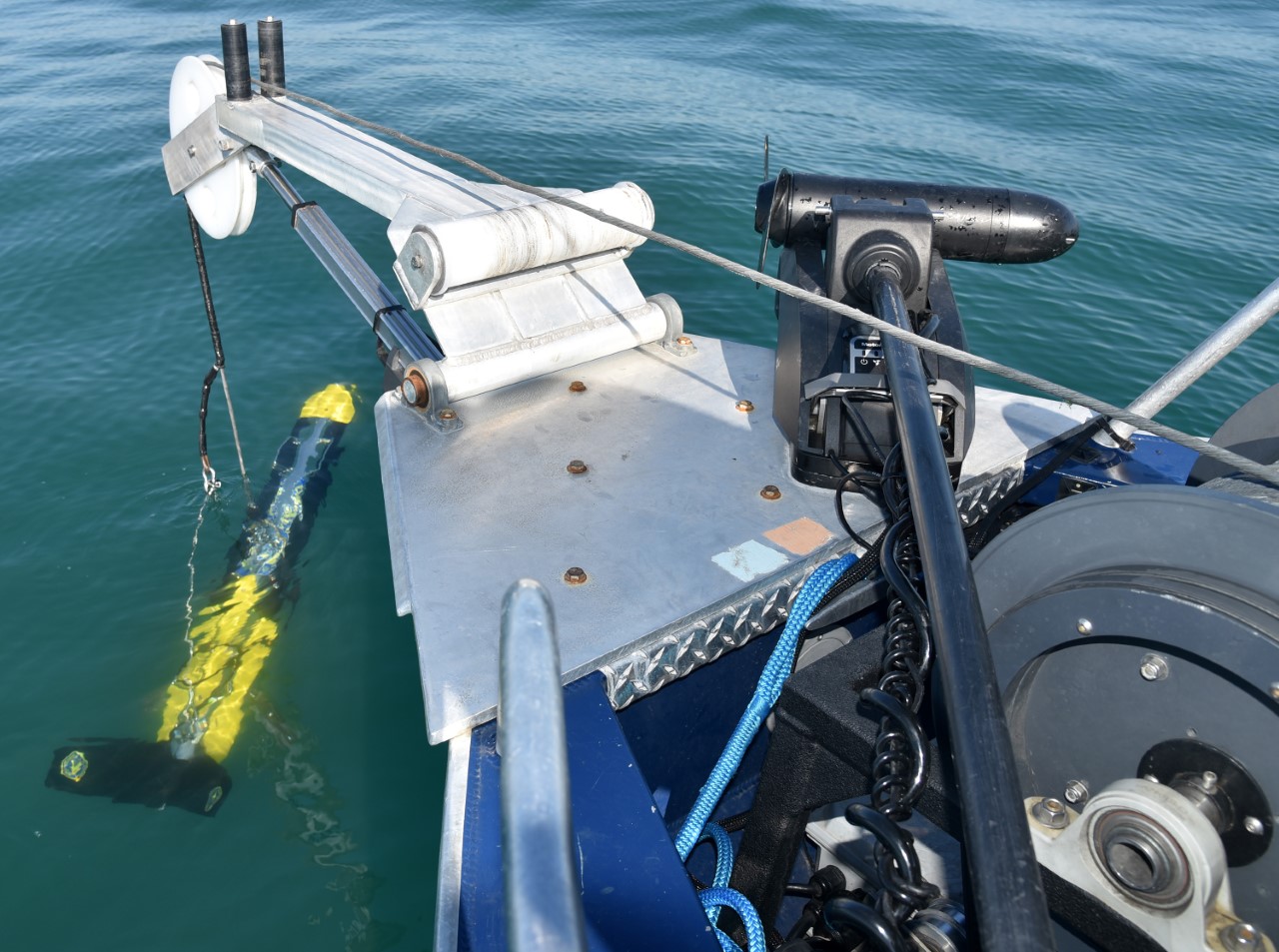

Bruce’s Legacy survives on donations, which help cover the $230,000 that Cormican has invested in a 22-foot Hewes boat rigged with a Klein MA-X View 600 side-scan sonar unit, an Outland remote-controlled mini-submarine, and joy-sticks, laptops, screens, and other gear.

Cormican’s high-tech equipment, strategic searches, and dogged scrutiny of scrolling underwater images make recoveries far more likely now than even 20 years ago. Until this century, side-scan sonar devices weren’t portable enough to sell commercially. Cormican’s fully outfitted rig looks futuristic compared to 20th century drag-hook tactics and the superstition-driven efforts that came before.

Sonar Replaces Guesswork

What passed for “search and recovery” strategies in the mid- to late 1800s sound comical today. Read “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” or “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” When Tom and Huck ran away to play pirates on a Mississippi River island with friends for a few days, the townsfolk thought they had drowned. One afternoon the boys saw a steam ferryboat and “a great many skiffs” approaching, with the ferryboat firing a cannon. Huck explained things:

“They shoot a cannon over the water, and that makes [the body] come up to the top. Yes, and they take loaves of bread and put quicksilver in ’em and set ’em afloat, and wherever there’s anybody that’s drowned, they’ll float right there and stop.”

When Huck and Tom’s friend Joe asked how bread knows where to stop, Tom replied: “Oh, it ain’t the bread so much. I reckon it’s mostly what they SAY over it before they start it out.”

Mark Twain scholars report Americans of that era still believed old British superstitions. The first, that explosive concussions above a submerged corpse rupture its gall bladder, causing the body to float. They also believed quicksilver, or mercury, made bread find and hover over drowning victims. A 1990 New York Times article said the belief came from the “biblical ‘bread of life’ and ‘quick’ or ‘living’ silver,” so named because of mercury’s free-flowing form.

Cormican only chuckled when asked if he’s tried either technique, as did one of his favorite pupils, Mike Neal, a marine conservation warden on Lake Michigan for the past 26 years. Neal, a veteran of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, investigates drownings and boating accidents and teaches courses around the country on boating fatalities and accident reconstruction for the National Association of State Boating Law Administrators.

“I suppose if you floated enough loaves, one of them might end up over a body, but I’d still bet on side-scan sonar,” Neal said. He also puts little stock in 1900s “technology” of “dragging” for drowning victims with grappling hooks.

“When I started [early 1990s] it was just drag-hooks,” Neal said. “Agencies would drag those around, supposedly on a grid system. But knowing what I know now, there wasn’t much method to the madness. We still investigated first and interviewed everyone possible, but we had to get lucky to find a body that way.”

‘Eating the Elephant’

Neal said searchers today have better tools. They study victims’ cell phone data, their boat’s GPS data, and sometimes onshore surveillance cameras. “Sometimes we can really zero in on the ‘point last seen,’” he said. “After that, we ‘eat the elephant’ one part at a time while working our way outward. With sonar and GPS, grid and parallel searches are precise.”

Most searches start by lowering a 4-foot torpedo-shaped sonar “tow-fish” within 15 feet of the bottom. Then they scan 125-foot widths on both sides of the boat as the driver “mows the lawn” at 4 to 5 mph. The only blind spot on images scrolling across the boat’s computer screens is a 10-foot gap directly beneath the boat. (Klein Marine Systems recently debuted a sonar unit that fills the gap.)

All the while—hour after hour, day after day—Cormican studies his computer screens, marking and enlarging possible targets. After covering a predetermined distance, his driver turns the boat around on a parallel course. They repeat the routine until they’ve inspected the entire area.

If an image warrants scrutiny, they make a cloverleaf of passes to view it from several angles. If a “target” resembles a body, they dispatch the ROV, or mini-submarine, for a closer look with its lighted cameras. If it’s a body—and depending on the depth, condition, and obstacles—they use the ROV’s mechanical claw-hand to grab a wrist or a leg just above the knee and haul the body up. In other cases—such as depths less than 100 feet when investigating divers want to inspect the site and recover the body—Cormican lowers a dog cage to the site on a line, which guides divers to the body and gives them a means to haul it up.

Wear a Damn Life Jacket

Some things nearly all of Cormican’s drowning victims have in common? They’re males who weren’t wearing a life jacket. The Centers for Disease Control report that 80% of drowning victims each year are male. And of 419 boating-related drownings cited in the U.S. Coast Guard’s 2019 Recreational Boating Statistics report, 362 victims (86%) weren’t wearing a PFD.

Neal and Cormican scorn any excuse for not wearing life-jackets, such as, “If I fall into cold water I don’t want to prolong the suffering by dying of hypothermia.” Cormican said he’s recovered only one body wearing a life-jacket.

“People can joke about it, but it’s selfish,” he said. “For their families, it’s nothing to laugh about. If you drown and disappear, you can’t imagine the impact on the spouse, kids, and their finances. They need closure, but you’re on the bottom and the coroner can’t issue a death certificate without a body. Without a death certificate, the family can’t get their insurance money. They’re on the hook for all your bills, and creditors want to be paid. If you wear a lifejacket, you have a much better chance of surviving. If you don’t, at least they’ll find you. That saves your family and the searchers a lot of trouble.”

And make no mistake: Most drowning victims quickly sink. According to the “Encyclopedia of Underwater Investigations” (2013), human bodies sink about 1.5 feet per second in saltwater and 2.5 fps in freshwater. If there’s no current, bodies generally sink straight to the bottom, drifting no more than 1 foot horizontally for each foot they drop. Those figures help recovery teams calculate and plan search areas.

Once submerged, some victims never resurface. If waters are 70 feet or deeper, Cormican said the water’s weight typically presses the body to the bottom, forcing out air and other gases, and reducing internal gas production. Further, as people drown, convulsions and coughing reflexes expel air from the lungs and contents from the stomach. Deep agonal gasps that follow pull water deep into the lungs and stomach. The “Underwater Investigations” author, Robert Teather, reports this process is so intense that half of the victim’s bloodstream consists of water within two minutes of the agonal-gasp phase.

Will it Float?

Once dead, bodies start decomposing, which produces ammonia, methane, sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide in quantities that vary by depth, water temperatures, and the victim’s diet, health, and body fat. If or when the body resurfaces depends on those factors.

“The healthier an individual [was], the more time the body takes to produce sufficient gas to refloat,” Teather wrote in “Underwater Investigations.” Given such variables, Teather considers it unlikely that science will ever reliably predict “refloat” times. Neal knows of Wisconsin cases where corpses resurfaced 2 1/2 to 10 years later.

Neal said the oddest occurrence he’s handled was a victim “standing” nearly vertical just below the surface. In another case, Neal found a man kneeling upright on the bottom. Neal said the “standing man” was a big-bodied triathlete with no body fat. Neal speculates that gases in the chest and abdomen floated the body, but dense muscles in the arms, legs, and lower body kept the corpse vertical.

Motivated by Empathy

No matter a drowning victim’s position, condition or location, Neal and Cormican said reporting the find to a family is easier than ending a search.

“It’s hard to face families after you find the body, but I’d rather do that than tell them we have to give up,” Neal said. “You want to give them closure. You don’t want them waiting weeks or months, wondering if the person will ever be found. You don’t want them going through all that uncertainty twice.”

Cormican echoed those sentiments. “So much of what they hear are rumors and speculation. I just focus on the family, and do my best to find answers for them.”

Still, retrieving bodies from the depths can cause nightmares. “I’ve had cases that made me jump out of bed in the middle of the night,” Cormican said. “I’ve seen some pretty hard stuff with people being on the bottom a long time, but it’s also the most gratifying thing I’ve ever done. I figure someone’s got to do this, so it might as well be me.”

Neal said “seeing some ick” is inevitable, but he, too, focuses on those left behind. “My worst week ever was six fatalities and seven bodies,” he said. “A boat crash killed four people, two kayakers drowned, and a body floated up after 23 months. I just reminded myself that someone else’s day is a lot worse than mine. If I can help a family somehow, I’m good with it.”