Louie Spray of Wisconsin caught three world-record muskies during his time.

His feat is written in stone, so it must be fact, right?

If you want that rock-solid proof, visit the Greenwood Cemetery in Hayward, Wisconsin and look up the burial site for Louis Bolser Spray, Feb. 21, 1900 — Nov. 19, 1984. Then walk to Block 9 and read his granite tombstone:

“HERE LIES THE REMAINS OF

LOUIE SPRAY

THREE RECORD MUSKIES

IN HIS DAY.”

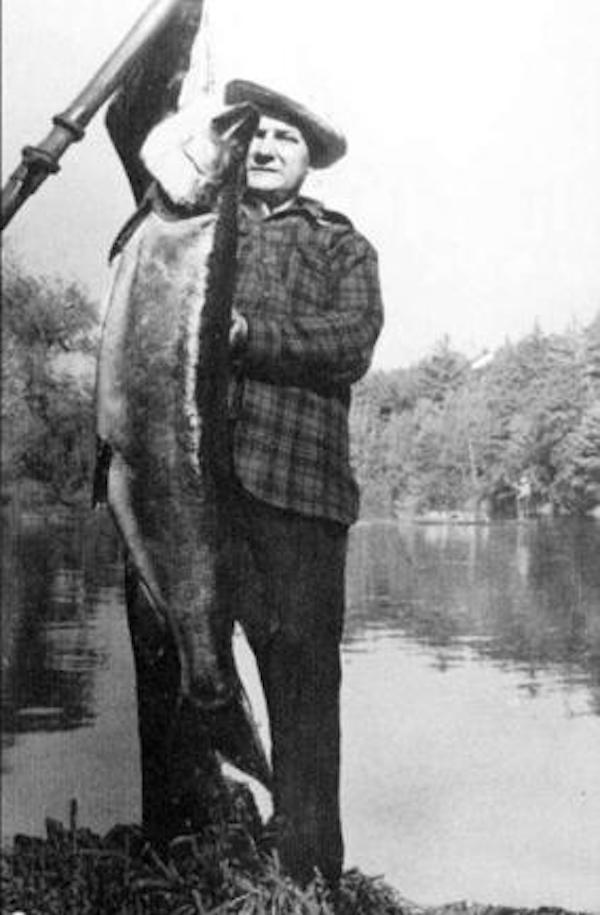

Spray’s biggest muskie—69 pounds, 11 ounces—holds the “All Tackle” muskellunge record in the Fresh Water Fishing Hall of Fame, which is also located in Hayward. The FWFHF’s record book says Spray caught the fish Oct. 20, 1949, on the 15,300-acre Chippewa Flowage 15 miles east of town. Spray previously held or claimed world records for muskies in 1939 with a 59.5-pound fish and in 1940 with a 61-pound, 13-ounce fish.

Records kept by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources also list Spray’s 1949 muskie as the state-record, and include its length, 63.5 inches.

You won’t, however, find Spray’s name or any of his monster muskies in the International Game Fish Association’s record book. The IGFA disqualified Spray’s biggest muskie in 1992 because one of his companions, George Quentmeyer, shot it twice in the head before he, Spray and Ted Hagg hauled “Chin Whiskered Charlie” into their wooden boat. Shooting big muskies boat-side was common in northern Wisconsin until outlawed in 1966, but it violates IGFA rules for landing fish.

Instead, the IGFA recognizes a Spray colleague, Cal Johnson, as its “All-Tackle” muskellunge record holder. Johnson caught his muskie—a 67.5-pounder—on July 24, 1949, three months before Spray’s big fish. He, too, was fishing near Hayward, but on the 5,139-acre Lac Courte Oreilles 16 miles southeast of town.

The FWFHF recognizes Johnson’s fish as the top muskie in its “Unlimited” category of line-class divisions, meaning his line exceeded 80 pounds.

Neither record-keeping organization recognizes a bigger muskie—the New York state record—a 64.5-inch fish weighing 69 pounds, 15 ounces. Arthur Lawton caught it Sept. 22, 1957, in the St. Lawrence River, the international boundary between New York state and Ontario, Canada.

Lawton’s muskie stood 35 years as the undisputed world record until 1992. That’s when muskie guide and Spray biographer John Dettloff of Couderay, Wisconsin, convinced the FWFHF and IGFA that Lawton had earlier entered the same fish in another contest as a 49.5-pounder. A joint press release by the FWFHF and IGFA in August 1992 purged Lawton’s muskie from their books. The FWFHF then restored Spray’s 1949 fish as No. 1, while the IGFA eventually elevated Cal Johnson’s 1949 fish to its top spot.

Disputed Champs

Those changes settled little in the muskie-hunting world. Fishing records, after all, routinely inspire doubt for countless reasons. Entries often bob and weave between conflicting state-by-state regulations and grind their gears when trying to align with the FWFHF and IGFA’s rules and categories. And unlike hunting records—which set standard minimums based on specific skull and antler measurements—fishing records include often-arcane distinctions between divisions, classifications, and “All Tackle” and “Unlimited” categories.

Further, with anglers desiring recognition for myriad fish species and fishing tactics, FWFHF and IGFA records are in constant flux. To avoid unwieldly listings, both organizations follow Ricky Bobby’s credo from the movie “Talladega Nights.” That is, “If you ain’t first, you’re last.” If your fish isn’t number one in the FWFHF or IGFA’s myriad categories, it’s not listed.

Therefore, you’ll find no top-10 lists or page-turning rankings of muskies, walleyes, largemouth bass, and other popular species in record books. Then again, compared to big-game record books compiled by the Boone and Crockett Club (nearly 1,000 pages with 32,000 entries) and Pope & Young Club (1,028 pages with 108,603 entries), fishing’s record books are modest. The 74-page FWFHF record book lists over 4,000 entries, and the 468-page IGFA record book lists about 350 pages of entries.

Even though Spray had his feats chiseled into granite in 1984, and the FWFHF and IGFA steadfastly back Spray and Johnson, respectively, for their number one muskies, debates about their legitimacy still rage. Many muskie fanatics—be they everyday doubters, defenders, or hardcore conspiracy theorists—chase “the truth” as obsessively as history buffs probing President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963.

Differing opinions generally stayed civil during the early 1990s as journalists like John Husar at the Chicago Tribune and Don L. Johnson, formerly of the Milwaukee Sentinel, debated in print Dettloff’s evidence that caused the FWFHF and IGFA to disqualify Lawton’s record fish in 1992. Among other things, Dettloff presented a painstaking analysis of Lawton’s fish photo, and concluded the muskie couldn’t have exceeded 57 inches, or 7.5 inches shorter than what Lawton claimed. Dettloff also calculated that Lawton’s muskie more likely weighed about 49 pounds.

Further, Lawton never presented a body. After photographing his muskie, and apparently not realizing its record potential, Lawton gave it away to be eaten. The photo he eventually submitted as evidence actually showed a muskie he caught a week earlier.

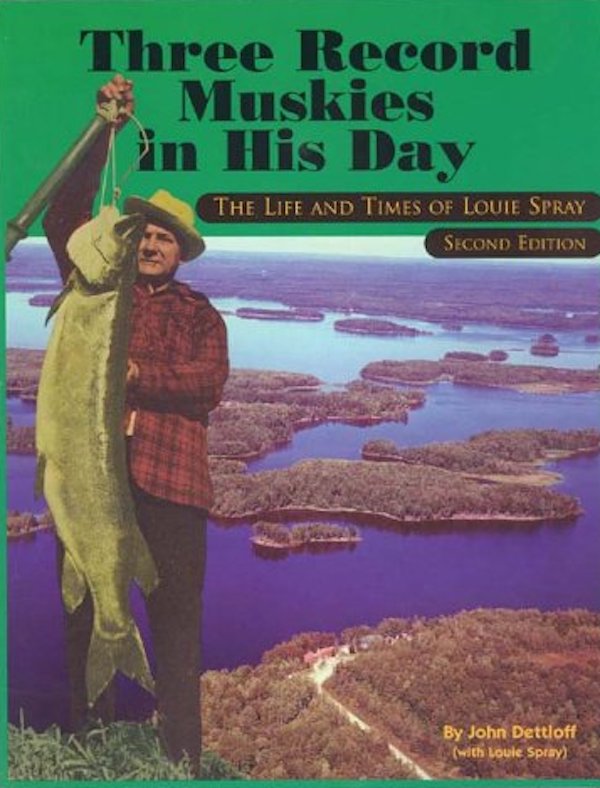

But Husar considered Dettloff an “amateur” investigator and “self-proclaimed muskie historian” bent on promoting Louie Spray and muskie fishing around Hayward. Dettloff’s 2004 book Three Record Muskies in his Day reprints Spray’s book My Musky Days and supplements it with several biographical chapters about Spray.

Who Was Louie Spray?

Husar also portrayed Spray as “a dark and glowering man,” and cited reports that he was once a pistol-packing rum runner who dabbled in prostitution and worked with mobsters who frequented his Hayward casino and tavern. In a June 1991 column, Husar reported a story told by Spence Petros, then editor of Fishing Facts magazine, who said Spray bought his 1949 record muskie for $50 from Joey “The Doves” Aiuppa, the alleged head of Chicago’s crime syndicate.

Aiuppa claimed he caught Spray’s muskie below the Winter Dam, which forms the Chippewa Flowage. As discussed in this article, mobsters and their bodyguards often fished illegally below the dam because the spillway teemed with big walleyes and muskies. Aiuppa told Petros he didn’t register the muskie as a record because he was “on the lam,” and couldn’t risk the publicity.

Husar also considered Larry Ramsell of Hayward the “premier historian” of muskie lore, given that Ramsell co-founded the FWFHF and first published his highly detailed book “A Compendium of Muskie Angling History” in 1984. Ramsell originally defended Spray and his records, but told Husar that Spray was a “cantankerous, ornery, old goat” who was “far from honest” and “enjoyed talking about his outlaw days.”

A Complex Man

Meanwhile, Don L. Johnson (no relation to Cal Johnson) liked Spray but conceded his complexities. In his 1992 article in Wisconsin Outdoor Journal, “Louis Spray, Musky King.” Johnson wrote: “Though much maligned in life and in death, Louie Spray was in many ways an admirable man. I knew him and liked him despite his freely admitted transgressions.”

Johnson first met Spray in 1951 after hiring on as the outdoor writer for the Eau Claire Leader-Telegram newspaper. Johnson approached Spray with skepticism. Johnson knew and trusted Ernie Swift, a legendary conservation warden who hounded mobsters and bootleggers during Prohibition and directed Wisconsin’s Conservation Department from 1947 to 1954. Swift considered Spray an outlaw, which led Johnson to think his investigative journalism would expose Spray and his muskie hoaxes.

But as Johnson checked out the innuendo and accusations surrounding Spray, he “uncovered a lot more discrepancies in those stories” than in Spray’s. “I became convinced he had caught that (1949 record) fish,” Johnson wrote. “Maybe he hadn’t caught it exactly as described. Almost certainly he hadn’t caught it where he had said. But he’d caught it all right.”

Spray said he caught the muskie on a 14-inch, live-rigged sucker that he jerked occasionally while Quentmeyer rowed. Spray said they focused their efforts on Fleming’s Bar after launching from Herman’s Landing, a nearby resort on the “Big Chip.” Spray stuck to his story, even though Tony Burmek, a local guide, said he fished that bar all day on Oct. 20, 1949 and never saw Spray and his two partners. Spray’s defenders, including Dettloff, excused him, saying anglers seldom reveal their best sites, and that Spray was merely publicizing Herman’s Landing.

Johnson said he and Spray were friends by the time he left Eau Claire for the Milwaukee Sentinel in 1962. He defended Spray against accusations of insurance fraud after a fire in January 1959 destroyed Spray’s office and the skin mounts of his three “world-record” muskies, a 46.5-pound muskie from 1911, a 42-pound muskie from 1938, a 16-pound walleye, and 25-pound northern pike.

Looking back in his 1992 Wisconsin Outdoor Journal article, Johnson wrote: “The three biggest muskies had been insured for $15,000 (not $25,000 as has often been reported) and could have brought more if Lou had simply offered them for sale.”

Rumors that Spray torched his building and fish mounts stung him. “He wondered how anyone could think he could destroy something so dear to him,” Johnson reported. “A big part of his life, of who he was, had gone up in smoke. He suddenly looked a lot older.”

Even so, Spray lived another 25 years. While battling cancer in November 1984, Spray, 84, shot himself in the head with a 16-gauge shotgun to end his suffering.

When the FWFHF restored Spray’s 69-pound, 11-ounce muskie as the world record in 1992, Johnson wrote: “Wherever (Spray) was, he had to be grinning like a jack-o-lantern. He is back in the spotlight, and he has been vindicated and restored to his throne. Controversy? Lou seemed to thrive on it.”

Challenging Spray’s Muskie

Maybe so, but Johnson wrote those words 13 years before a group called the World Record Muskie Alliance submitted a 93-page report to the FWFHF challenging Spray’s record. The WRMA included Ramsell, the muskie historian; and famous muskie anglers like Pete Maina of Hayward and Jim Saric, editor of Musky Hunter magazine. The group’s 2005 report called Spray an “incredible cheat” whose chief talent was turning large muskies into “cold, hard cash.”

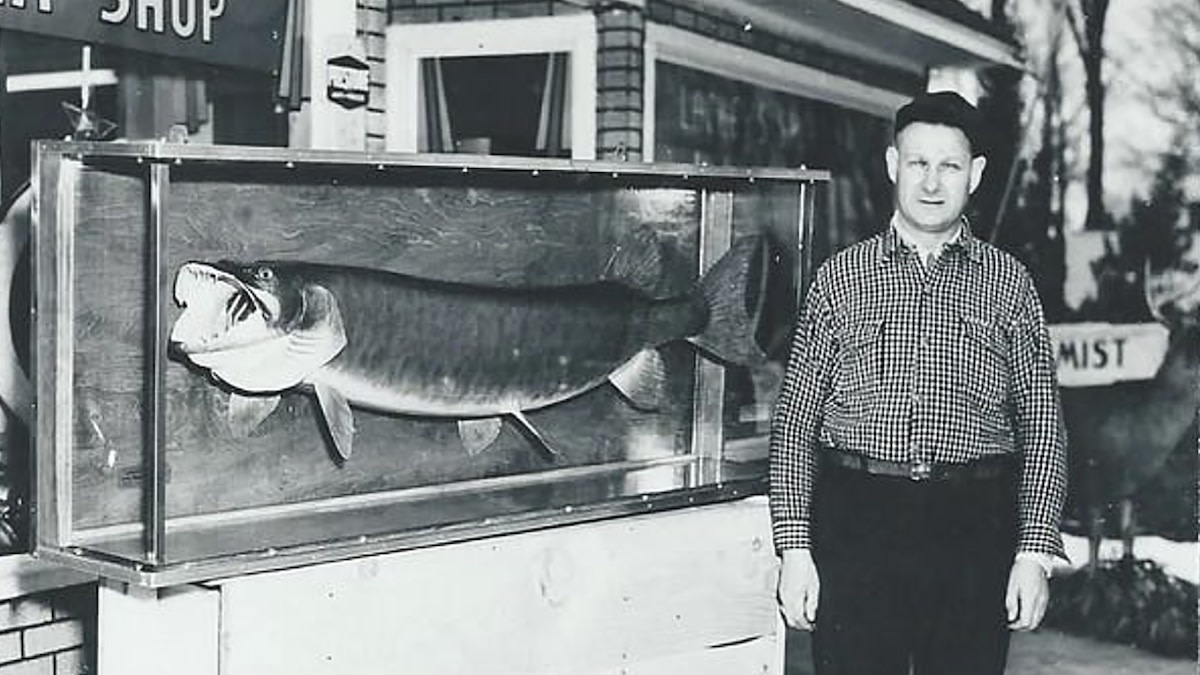

The group hired a Canadian company specializing in photogrammetry to analyze photos of Spray’s record fish to determine its actual size. The technicians determined the muskie measured between 52.1 and 55.1 inches, not the recorded 63.5 inches. The DCM experts also said the muskie was 8.2 to 9.2 inches wide, dimensions that couldn’t achieve the recorded 31.25-inch girth.

The technicians also analyzed photos of the muskie’s skin mount and concluded it had been “augmented” by about 14.5 inches in length and 8.51% in belly width. The report’s authors said such discrepancies proved Spray helped “perpetrate a fraud of historic proportions.” The WRMA recommended the FWFHF disqualify all Spray entries from its current and historic records.

The FWFHF instead upheld Spray’s record in January 2006 and quoted three university mathematicians to justify its decision to ignore the WRMA report. The three professors—from the University of Minnesota, UM-Duluth, and Columbia University—responded with a protest letter in February 2006, stating the FWHFH did not understand their analysis. The professors recommended the Hall impanel an independent group of mathematicians and photogrammetry experts to examine all evidence. The FWHFH ignored the professors’ suggestion.

When contacted by MeatEater, FWFHF executive director Emmett Brown said Spray met all requirements when submitting his muskie to recordkeepers in 1949. Brown also said the Hall did not keep a written record of its January 2006 decision rejecting the WRMA’s recommendations.

Critics like Ramsell, however, questioned why the FWFHF used Dettloff’s self-taught analysis of historical photos to eliminate Lawton’s record, but rejected an analysis by photogrammetry experts to uphold Spray’s record. Ramsell resigned as the FWFHF’s world-record historian on Dec. 30, 2005, but also said he wouldn’t renew his WRMA association. He told the Chicago Sun Times: “Personal animosities got in the way of the examination of the facts. Both groups acted unprofessionally.”

Challenging Johnson’s Muskie

In June 2008, the WRMA next challenged the IGFA with a 34-page report that concluded Cal Johnson’s 67.5 pound muskie from 1949 was also a fraud. Again, the same photogrammetry specialists examined photos of the muskie and found its size exaggerated. The technicians found it measured 53.2 inches. Further, a peer review by a forensic imaging firm estimated the muskie’s maximum length at 54 inches.

Both analyses fell short of the 60.25-inch length listed in affidavits for the muskie. After applying calculations to the recalibrated lengths, the WRMA found Johnson’s muskie likely weighed 25% less than its world-record listing. Given that evidence, the WRMA recommended the IGFA remove Johnson’s muskie as its all-tackle world record.

As with the FWFHF, the IGFA rejected the WRMA’s report and recommendation. Cal Johnson’s muskie remains the organization’s all-tackle record holder. In a February 2009 email, the IGFA’s Jason Schratwieser told WRMA president Rich Delaney: “Your report has been vetted at the highest possible level at IGFA. We simply do not feel the photogrammetry analysis is sufficient for us to rescind this record. We are resolute in this matter.”

Moving On

Ramsell updated his book A Compendium of Muskie Angling History in 2007 and 2010, expressing deep regret he long supported Spray. He also wrote a scathing detailed 146-page denunciation of Spray and Cal Johnson, and those who defend them. Ramsell shares his exhaustive reports on muskie controversies here.

Even so, Ramsell, Brown and others think it’s best to now leave the historical muskie records alone. “It’s hard to unring that bell,” Brown told MeatEater. “A fish is a fish whether it’s caught in 1940 or 2022. We’re satisfied our records met all criteria possible.”

Agree or disagree, Spray and Johnson’s records seem intact, and the debates less dramatic. Bill Gardner of Eagan, Minnesota, wrote the 1982 fishing classic Time On the Water: One Man's Quest For the Ultimate Musky. Gardner said he’s never had strong opinions about any muskie, no matter its size, status, or who caught it.

“Muskie fishing is full of Type A personalities, and that’s part of the problem,” Gardner told MeatEater. “It’s easy to find three major figures with strong opinions about any muskie and each other. You can follow whoever you want, but once they start talking, records soon get lost in the background. Many muskie fishermen simply don’t like each other.”

Jordan Weeks, a fisheries biologist with the Wisconsin DNR, is a self-described member of the “muskie-fishing cult.” But he won’t choose sides. “We should just acknowledge the old records, appreciate those great fish, and move on,” Weeks said. “Do I think Louie Spray and Cal Johnson caught muskies that weighed nearly 70 pounds? It’s unlikely, but not impossible. I’m in no position 70 years later to call anyone a liar or rule on any fish. I wasn’t there.

“But I know this: We don’t see muskies that big today,” Weeks continued. “The biggest I’ve seen measured 60 inches, and I’m not sure our agency has verified a 60-pounder. We’ve handled multiple 50-pounders on Green Bay, but our survey nets are too small to catch the biggest muskies. When big ones hit the sides of the net’s entry funnel, they usually back out.”

Would the squabbles end if someone caught a legitimate 70-pound muskie? Maybe, but that’s unlikely. For one, many anglers won’t risk injuring a huge fish by boating and weighing it. If it died, they’d incur the wrath of all other muskie hunters. Many are more apt to grab a tape, camera, and fish cradle to document its length boat-side before turning it loose.

70-Pounders and 50-Inchers

Most likely, though, legitimate 70-pound muskies don't exist. Professor John Casselman, a legendary muskellunge and northern pike researcher at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, said muskies simply can’t grow that large.

“It’s all about longevity, low fishing pressure, particle size of prey, optimum water temperatures for growth, and large, fertile waters with lots of places for muskies to lurk,” Casselman told MeatEater. “Few places have all that. For a muskie to reach 60 pounds, it needs to be in the water 32 to 35 years. That’s a lot of surviving. Catch-and-release helps more fish grow old, but even 2% mortality rates take a toll over three decades. I think we’ll see greater growth in muskies and their prey as climate change pushes water temperatures into (the high 70s) across the Great Lakes basin, but I doubt we’ll see muskies reaching weights beyond the mid- to high 60s.”

Weeks agreed, saying record-book muskies will always be the exception. “We have more muskies, more muskie lakes, more muskie hatcheries, more muskie range, and more muskie-fishing opportunities than ever before, but that doesn't mean more record-book muskies,” Weeks said. “Twenty years ago in Wisconsin, our surveys found it took 100 hours to catch one 34-inch (legal) muskie. Today it takes 40 hours or less to catch one. But all muskies grow at different rates, and none live forever.”

Perhaps that’s why Jim Olson, a veteran row-troller and longtime member of Muskies Inc. in Madison, Wisconsin, only sees humor in the tales and disputes about record fish.

“My goal remains a 50-inch muskie,” Olson said. “I even caught one once, but it was during a tournament so they made me measure it. I’ve always said there’s two activities where a man can exaggerate by an inch, and one of them is muskie fishing. My tape said 49½ inches that day, so that’s what I told the scorekeeper. I tell everyone else it was 50 inches.”

Casselman likes that approach. “It bothers me when people work so hard to prove other people wrong,” he said. “I wish they’d talk more about the great fish they caught, and work to improve their prowess. I know Louie Spray caught some beautiful fish, but I don't know enough about any of them to discuss their age, weight, or growth rates. They’re history now, and there’s probably nothing more to be learned.”