You might be skeptical about this title. Hell, I would be too, but hear me out. The greatest North American sportfish you’ve never heard of? The inconnu.

No need to “bless me,” that wasn’t a sneeze.

Inconnu, defined by Merriam-Webster as an “unknown person or thing,” is also the common name given to this particular fish species by early explorers to Alaska. The “unknown fish,” per se, very fitting.

If you live outside of Alaska, you’d be forgiven if you’ve never heard of inconnu. Native Iñupiaq peoples of Alaska call this fish “sii,” pronounced “she,” the root of most common name you may have heard—sheefish.

Today, mystery and lore still surrounds the often inconspicuous sheefish, which resides only in the far north of Alaska, Canada, and Siberia. That said, among anglers in the know, inconnu have also earned the moniker “tarpon of the tundra.” Given that actual tarpon are often considered the world’s greatest sportfish, sheefish, in my opinion, are thereby worthy of consideration for “North America’s greatest sportfish you’ve never heard of.”

First things first. Sheefish are sportfish and sheefish are whitefish. In many trout waters of the Lower 48, whitefishes are generally overlooked as sportfish and maligned by anglers who might think they’ve hooked into a 20-inch, non-native brown trout only to discover a native, 16-inch whitefish at the end of their tippet. All this despite the fact the whitefishes belong to the same family (Salmonidae) as revered trout and salmon species.

But sheefish are in a class of their own—if you’re unfamiliar, let me introduce you.

Sheefish via Randy Brown.

Sheefish via Randy Brown.

Meet Sheefish Sheefish (Stenodus leucichthys) are the largest member of the whitefish subfamily—from Greek, “stenos” meaning narrow, “odous” meaning teeth, and leucichthys meaning white fish. With a gaping, tarpon-like mouth and sandpaper teeth, big sheefish can grow in excess of 40 inches and exceed 40 pounds. The record sport-caught sheefish in Alaska registered at 53 pounds. That’s some prestige and lore, but sheefish are still relatively understudied and unknown across their range.

Randy Brown is a Fairbanks, Alaska-based fisheries biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and a recent recipient of the Rachel Carson Award for Exemplary Scientific Accomplishment. He’s a living legend in the Alaska fisheries scene and recently returned from a two-week stint of sheefish fieldwork near the Alaska-Canada border.

“There’s a population of sheefish out there, and we don’t know a damn thing about them yet,” Brown told MeatEater. His current work involves radio tagging adult sheefish to track their movements and garner a better understanding of how and where they survive in that particular area.

In some ways it’s actually incredible—in the year 2021, we are still working to understand basic life history and population dynamics of sheefish, the “unknown fish.”

That said, Brown’s research experience with sheefish spans the greater part of 25 years and he’s had a hand in discovering much of what is known about their populations across Alaska. Brown and colleagues have described distinct populations of sheefish throughout the Yukon River drainage as well as Kobuk and Selawik river drainages in northwest Alaska. This vast and wild country that sheefish call home adds to their lore and mystery.

During early tracking research on the Yukon in the 1990s, Brown and his team traveled over 1,000 miles by boat to locate aggregations of spawning sheefish. “Some populations are anadromous, and some populations remain in freshwater their whole lives,” Brown said. “Similar to salmon, sheefish don’t eat during their spawning migration.”

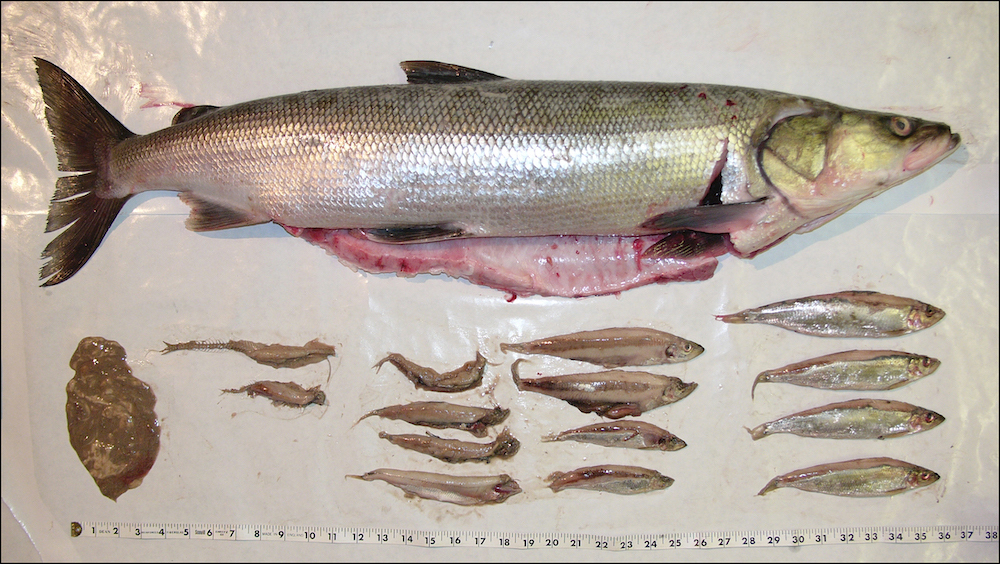

Adults typically mature between 7 and 10 years old, and the oldest fish live nearly 40 years. By late September or early October, inconnu are on their spawning areas, which are typically stretches with fine gravel for proper egg deposition and incubation. Adult females can carry eggs that account for 20 to 30% of their body weight. These hundreds of thousands of eggs help make up for their relatively slow maturation. Prior to the annual migration, sheefish are busy loading up with all the food they will need to survive spawning and the long, harsh winter.

“For some populations of sheefish, after spawning, individuals return to the same area of mainstem rivers each winter. I think they just hunker down and don’t eat much all winter. But there are other populations that make their way back toward the ocean and feed pretty heavily throughout winter,” Brown said.

In fact, the latter foraging strategy was first “scientifically” described by a school science project that Brown helped advise. The project that reached science fair competition at the national level. Even still, today, “with the variability among populations, there’s still a lot to figure out,” Brown said.

Stomach contents of a sheefish via Randy Brown.

Stomach contents of a sheefish via Randy Brown.

How to Catch Sheefish In recent years, Fairbanks guide Trevor Smith has begun to dial in sheefish angling on their summer feeding patterns. Smith, somewhat by chance, put MeatEater’s own Joe Cermele on his first sheefish a few years back during a pike fishing expedition. He now focuses on confluences of clear-running tributaries with muddy mainstem rivers such as the mighty Yukon.

“They will stack up there at the seam, where the clear tributaries meet the silt line, and in nearby eddies to eat juvenile salmon and whitefish coming out of the tribs. We’ve basically found that deadsticking a spoon on the bottom, with an occasional pop to stir up the substrate and catch their attention, will get them to strike,” Smith said. “Their take is unmistakable, it’s like a Hoover vacuum.” A classic red-and-white Daredevil will get the job done in these conditions.

For fly anglers, Smith stressed sinking line and tungsten weights to get streamers into the strike zone—the water at productive confluences can be 20 feet deep or more. “There’s no real false casting involved, you’ve got to load up on a single backcast and get the fly down the water column as quick as possible,” Smith said. Just like fishing a spoon, a couple pops off the bottom will often trigger a strike.

In other rivers that generally run clear, catching sheefish can be more of an active process. It can also take patience to find active fish. But patience can pay, and you’ll want to be ready. Sheefish don’t just look like tarpon, they fight like one too—with all the aerial performance and screaming runs you’d expect from the Silver King.

As Kevin Fraley, a PhD fisheries biologist and avid pursuer of sheefish, told MeatEater, “I’ve had better luck sizing up hooks, using pike streamers and the like. There’s something about how they take a lure or fly, along with their mouth morphology, that can make it difficult to get a solid hookset otherwise.” But, if you hook up, and are able to land a healthy adult, the table fare is worth the effort.

How to Cook Sheefish Villages and communities across remote Alaska use “sii” for subsistence. The predictably white flesh of sheefish makes for a delicious meal out of a fry pan, and a nice-sized fish can produce a number of meals. Like other whitefishes and salmonids, they also smoke well, and Native Alaska communities have long dried and preserved inconnu in this manner to provide protein throughout the long and harsh Arctic winters. This spring, Fraley hooked into a number of sheefish on a “secret” early season pattern, and harvested a few to share. This was my first taste of the tundra tarpon and I can now attest that their flesh has impeccable flavor and texture, especially tasty as a po’boy-style sandwich.

If you’ve been fortunate enough to experience sheefish on the dinner table or hook and line, you won’t soon forget about it. In fact, even for many residents of Alaska, catching sheefish is a bucket list item. I would argue the fact that locals hold these fish in such regard, in and of itself, qualifies inconnu as the greatest North American sportfish you’ve never heard of. Now that you have heard of them, you might want to start planning to meet one in person.