Once you’ve found your quarry, it’s time to start thinking about whether or not you should attempt to make a stalk. Sometimes the answer is perfectly clear.

If you spot an antelope feeding casually out in a sage patch in an upwind direction and you’ve only got to make a 50-yard crawl to get to a good shooting position, you should probably start crawling immediately.

Prey Movement

But at other times, particularly when there’s a lot of distance to cover, the answer might not be so clear. You’ve got to ask yourself this question: Considering the distance between the animal and me, will the animal will still be there, or somewhere where I can find it, when I arrive at its location? This isn’t the sort of question that can be answered with certainty, as animals are unpredictable in their movements and there are many unseen factors at play.

For instance, you might be stalking a group of antelope that have been milling around in the same place all day and then have another hunter spook them while you’re closing the final part of your stalk on your hands and knees. There’s just no way for you to control that sort of thing.

But you can make fairly accurate predictions about what an animal is going to do and where it’s going to be if you take the time to observe both the animal and its surroundings. While there’s no way to account for every scenario that a spot-and-stalk hunter will encounter in the field, there are a number of general guidelines that will prove helpful as you try to gauge whether or not to make an attempt on a distant animal.

During the breeding season or rut, mating activity is one of the best things you can see. If you glass a male who’s harassing or defending a group of females, chances are strong that he’s going to stay in that area unless the females move.

Conversely, it’s generally a bad idea to take off in pursuit of spooked animals. If you hear a few rifle shots and then see a herd of elk disappear over a ridge, don’t assume that they’re going to be standing on the other side of that ridge when you get over there. Even if a nervous or spooked animal is standing in plain sight, it’s still a good idea to hold off on your stalk until the animal calms down and goes back to feeding or resting.

But not all fast-moving animals are spooked. They might be cruising for mates during breeding season, or moving between feeding/watering/bedding areas, or traveling in search of new food sources. Regardless, try to determine where the animal is headed and let it get there. This is especially true if the animal is moving away from you, as it’s extremely difficult to overtake traveling animals without alerting them to your presence. With that said, keep in mind that getting out in front of a traveling animal is an excellent strategy.

If the animal’s line of travel is predictable, and you can head it off, go for it. Feeding is another good sign, as it means the animals are generally content and not at immediate risk of moving away too quickly. However, they will move somewhat. If a group of animals is grazing, pay attention to which direction they are facing. They will usually face into the wind. Plan on them moving at least somewhat in that direction.

Consider the time of day when you’re looking at feeding animals. In the evening, there’s a strong likelihood that they’ll stay in the same general area until dark. In the late morning, however, their feeding period might soon come to an end as they head to their bedding locations.

Speaking of bedding areas, there’s a strategy which is utilized by highly disciplined hunters that’s sometimes referred to “putting them to bed.” The strategy is useful when you’ve located an animal that might be difficult to approach, or when you’re in a situation where you want to absolutely minimize the chances of spooking an animal that you’ve selected as your target. It amounts to waiting for an animal, or a herd of animals, to settle into their bedding area before you proceed with a stalk.

Sometimes, particularly with alpine game, you’ll actually see the animal bed down. But it’s much more common to have the animal disappear into some sort of thick vegetation or bedding cover. When a half hour or so goes by without the animal emerging, it makes sense to think that it might have bedded down.

At this point, you can be moderately certain that the animal won’t move for a while. If it’s lying in a position where you can approach without detection, it’s time to attempt a stalk. But don’t make the mistake of thinking of a bedded animal as purely static.

Very few critters will bed down and then just lay for hours on end without moving. They get up and reposition for any number of reasons: to stretch, to find some shade or sun, to urinate, to have a few bites to eat, or to chase off a herd-mate that’s gotten too close. Every experienced spot-and-stalk hunter has had carefully planned stalks blown by supposedly bedded animals that were actually up on their feet and moving about.

Usually, your goal isn’t to kill the animal while it’s lying down. Not only is shot placement difficult on bedded animals, but getting into a position where you can actually see a bedded animal can often lead to mistakes and spooked game. It’s generally preferable to stalk within range of where you expect the animal to emerge when it leaves its bedding area to begin feeding again, or to a place where you might be able to get a clear shot at the animal when it stands up. You then wait there, patiently, until your opportunity arises.

If you hunt often enough, you’ll eventually locate an animal that seems virtually impossible to stalk. Maybe it’s a wild hog that spends all of its time in an oak thicket where you’d never find it once you got close enough for a shot, or maybe it’s a mule deer with a 360-degree view of the surrounding sage flat and there’s no reasonable avenue of approach. In these situations, it’s far better to observe the animal than it is to rush a stalk that will almost certainly fail.

By observing an animal, you’re doing something called patterning. That is, you’re learning how and when the animal uses the overall context of its home range. Where and when does it eat? Where and when does it sleep? Where and when does it go for water? What routes does it travel when going from one of these areas to the next? By answering these questions, you can put together a schedule of the animal’s habits and hopefully identify some places and times when it’s vulnerable to a carefully executed stalk.

This might be a late morning moment when that hog crosses an opening in the oak brush on its way to a shaded bedding location. Or it might be a midday window of time when that mule deer disappears into a creek bed for water, staying down there just long enough for you to cross the sage flat without being seen.

Now for the actual stalk. Because losing track of the animal’s location is perhaps the number-one mistake made by spot-and-stalk hunters, be sure to mark the precise position of your quarry before you begin approaching it. Do this whether the animal is a hundred yards away or two miles away. Make a mental note of prominent or easily identified landmarks–trees, clusters of brush, rocks, etc. that can help you stay oriented during your stalk.

Remi Warren, an avid and very successful big game hunter, often photographs his stalking route before he leaves his glassing perch, so that he can refer to the image if he gets confused about where he is. Another trick is to take a compass bearing on the animal’s location, in order to keep you from veering off course during your approach.

Better yet, try to pinpoint the animal’s location on a topographic map or GPS unit. In the case of GPS, you’ll have the luxury of real-time information throughout your stalk about how much ground you’ve covered and how far you’ve still got to go.

Make sure to mark the location of your glassing perch on your GPS unit as well, because it’s helpful to have that point as a reference while stalking. And if you’re hunting in areas with high relief, make a note about whether the animal is higher or lower than your glassing perch, and then use relative elevation as yet another way to keep yourself oriented during a long stalk across a landscape that will almost inevitably confuse you.

Select the most direct route that you can without risking that you’ll be in line-of-sight with the animal. You want to get there as quickly as possible, so long as you don’t take unnecessary risks of exposure.

In a perfect world, there would always be a ridge running parallel to your line of travel, and all you’d have to do is duck behind the ridge while closing the distance.

Then, when you got close, it’d be a simple matter of peeking over the crest of the ridge and making your shot. But in the real world, stalking usually involves a route that takes advantage of many different features along the way.

You approach the stalk like a dot-to-dot children’s sketch, just moving from one position to the next with an end goal of arriving where you want to be. Use brush, rocks, and undulations in the ground. Wear camouflage, or earth tones, and don’t be afraid to get on your hands and knees or slither along on your belly like a snake.

Sometimes you’ll simply run out of cover, and then you have to move only when the animal is feeding or looking in another direction. In unbroken landscapes, one might conduct an entire stalk by moving only when the animal is feeding.

Always Know and Play the Wind

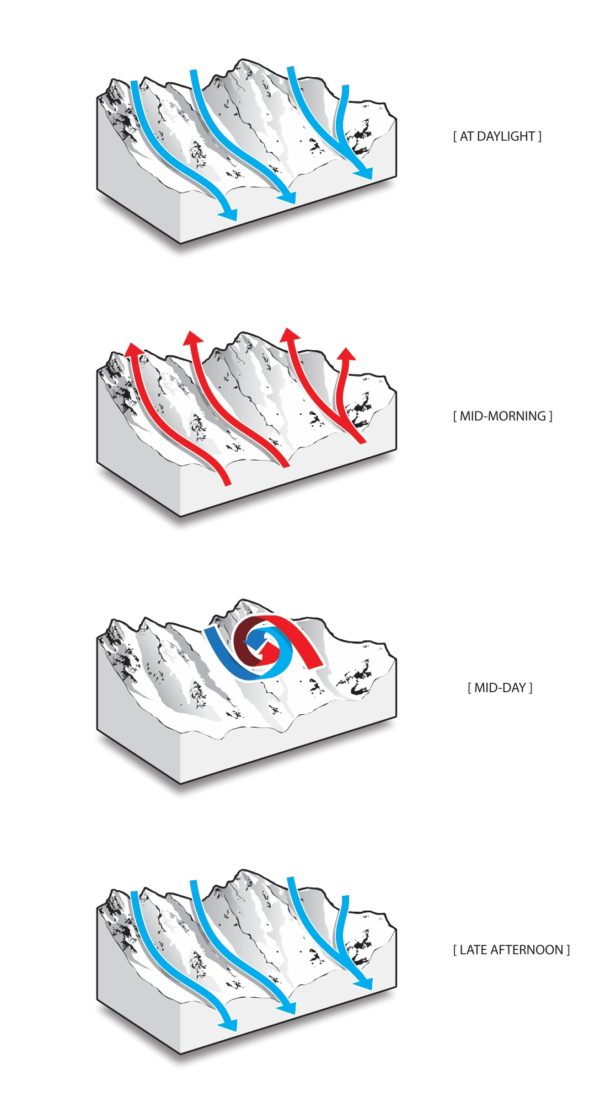

At all times, remember to pay attention to the wind. Concealing your odor is even more important than concealing your body, and this can only be done by constantly monitoring the wind direction. Sometimes the wind is so faint that you can’t even feel it on your skin, but it’s still plenty strong enough to carry your odor to the animal and give you away.

To monitor wind direction, you can use a commercially produced puffer, which puts out little clouds of easily blown talc powder, or you can take a piece of dental floss and tie a bird’s breast feather to the limb of your bow or the front sling-stud of your rifle. Milkweed seeds or cattail down kept in a chewing tobacco tin also work well; toss a pinch into the air and watch which way it blows. Whatever your method, check the wind often during a stalk.

On flat ground, the wind is usually steady and predictable, but in the mountains or other rough ground the wind can be impossible to predict from one moment to the next. When the wind is right (blowing from the animal to you), proceed with your stalk. When the wind is wrong (blowing from you to the animal) back out and reassess the situation. Remember, an animal might question it’s own eyesight– sometimes they’ll see you and still not spook. But an animal never questions its nose.

Hand Signals for Stalking

When hunting with a partner, try having him or her stay at the glassing position while you move into range. With a few prearranged hand signals, your partner can help guide you toward the animal. And if the animal moves or spooks during the stalk, this information can be relayed to you in time for you to adjust your plan.

The spotter is also a valuable asset in post-shot situations because they’ll be more likely to see how the wounded animal behaves and which way it travels. In states where two-way communications between hunters is legal, it is possible to use radios in place of hand signals. But many hunters regard this as an ugly and unwelcome intrusion of technology, and reputable big game scoring organizations prohibit the admission of animals killed with the help of two-way communications.

Stalking with a Bow

There’s an old saying that goes, “where a rifle hunt ends, the bow hunt begins.” This refers to the fact that a bowhunter must creep in way closer to his quarry than a rifle hunter. At such close distances–anything less than a hundred yards, really– there are a million or things that can go wrong. The rolling of a rock or the sound of brush against fabric is all it takes to send your animal bounding away.

A bowhunter needs to be extra careful when choosing his route. As you draw near, make a plan for each and every placement of your foot. Look for grass clumps and soft dirt rather than dry leaves or loose rock. Movements must be slow, and never jerky or abrupt. Using a rangefinder can help immensely when selecting your final shooting position.

If you’re maximum shooting range is 30 yards and your quarry is 60 yards away, use your rangefinder to select an object that splits the difference. This eliminates the need to use your rangefinder again when you’re even closer to the animal, which cuts out extra movements that might give you away.

Finally, keep in mind that you’ll need a final bit of protection when you rise up to draw your bow, a substantial movement which will not generally go unnoticed. Use a tree, a patch of bush, a topographical feature, or a rock to hide the movement. Then, once you’re drawn and ready, you can step away from the cover and rise to shoot.

A Handful of Extra Tips for the Spot-and-Stalk Hunter

- Bring along a butt pad. It helps you stay comfortable while glassing, which helps you spot more game, which helps you harvest more meat. Good pads can be made by cutting off two sections from a Thermarest Z-Lite foam pad. It’s a light and durable option, and if you split the original pad with two or three of your buddies, it’s also cheap.

- When archery hunting, it can be difficult to carry your bow while trying to keep a low profile during a stalk. Attaching it to your back while belly crawling will work, but the system requires fasteners and can put you in a tough position if you need to make a quick, unexpected shot. When the terrain allows it, a better method is to crab crawl with your bow laid across your lap. You can do it with an arrow notched. And when the time comes, you can come to a kneeling position in one fluid motion and make your shot.

- If you’ve finished your stalk but the animal is not where you thought it would be, stick with your plan and wait it out. Often the animal is just behind a tree, or has bedded down. All it takes is a little patience on your part before the animal will move and give away its position.

- In the final phase of a stalk, complete silence is a necessity. Many serious hunters carry a soft-soled form of footwear such as thick socks, running shoes, or manufactured “stalking shoes” such as Cat’s Claws or Bear’s Feet that can fit over one’s hard-soled boots. These can all but eliminate the sounds of your footsteps.