We’ve all heard about a “raging debate” over copper bullets and whether they belong in America’s big game hunting scene. But credible criticisms of copper bullets disappeared in recent decades as design and technology kept improving these deadly, hard-hitting slugs.

Copper wasn’t the first metal to try replacing lead in hunting bullets. Aldo Leopold, for example, swore off iron-forged bullets in his 1920s story “A Turkey Hunt in the Datil National Forest," where he wrote:

“Some people shoot steel bullets at turkey. This is a big mistake. I once knocked down three big birds with steel bullets and two of them got up and flew a half-mile. I never saw them again. The same season, while turkey hunting, I knocked down three big lobo wolves and two of them got away. I am cured of steel bullets.”

Roughly 60 years later in 1985, Randy Brooks of Barnes Bullets began work on solid copper bullets. In 1989 he introduced the Barnes X Bullet in six diameters from .270 to .416. As veteran gun writer Bryce Towsley of Vermont says, skeptics met the X Bullet with arms crossed defiantly.

“Those so-called experts said the X Bullet was a bad idea and would never work,” Towsley said. “They didn’t give it a chance until it proved itself in Africa. It just needed some tweaking, but then it had to fight relentlessly against a reputation for poor expansion and fouled barrels. If you listen, you’ll still hear guys repeating criticisms they heard 30 years ago.”

Serious big-game hunters, however, mostly praised the Barnes X, with its deep, narrow hollow point that splits upon contact into four jagged petals to form an “X,” hence its name. Its body, meanwhile, retains almost all of its weight to ensure deep penetration.

Barnes further improved its bullet lineup in 2003 with the Triple-Shock X. The TSX bullet has rings around its shank so it performs better in more rifle-bore diameters, and its updated nose design improved expansion. Those and other advances also reduced bore fouling and increased accuracy.

Getting Sidetracked A few years later, however, Barnes and other bullet makers faced issues they couldn’t solve through metallurgy and better engineering. By 2008 researchers were linking sick or dead California condors, Western golden eagles, Midwestern bald eagles, and other birds and mammals to toxic flakes of lead-core bullets that scavengers swallowed while feeding on bones and gut piles of gun-killed deer, elk, and bears.

About the same time, public health officials and wildlife agencies began testing deer roasts, steaks, and ground venison for toxic residue after a North Dakota doctor reported lead in meat donated to food banks. Hunters and processors have since learned to reduce fears and risks of lead contamination by trimming and discarding all blood-shot meat; not tossing it into the grind pile to boost yields.

Still, fears of lead poisoning linger. Some critics say states aren’t doing enough to ensure the safety of donated venison, and anti-hunters use both issues to oppose all hunting. Meanwhile, non-hunting critics demand hunters use lead-free “green” bullets that can’t poison raptors or four-legged scavengers. In 2019, California became the first state to ban lead bullets for hunting.

Objective observers might assume those circumstances boosted copper bullets’ stock, but gun issues seldom follow straight lines. Some hunters started viewing monolithic bullets suspiciously. Doubters dubbed them “hippy bullets,” and refused to use any projectile that “enviros” endorsed. Some even claimed that copper-bullet proponents concocted “get-the-lead-out” campaigns to cynically boost sales.

Dave Clausen of Amery, Wisconsin, recalls a friend who thought that way. Clausen, a veterinarian, switched to copper bullets for deer hunting after finding “significant” lead contamination in three of 20 venison packages he X-rayed after processing a deer himself in 2009. Clausen showed the X-rays to a good friend and suggested he also try copper.

“He went ballistic,” Clausen recalled. “He forcefully told me this was all a bunch of anti-hunting B.S. He said copper bullets were no damn good, and gave me four boxes of Barnes TSX bullets that a relative had given him.”

A Solid History It didn’t matter to Clausen’s friend, of course, that copper bullets proved themselves deadly, accurate, and easy on rifle bores long before anyone found lead slivers in ground venison or linked lead bullet residue to dead or dying scavengers. Towsley, for example, said he’s been shooting copper bullets since an X Bullet from his .35 Whelen took out both shoulders of a bull moose in the early 1990s.

Ron Spomer of Idaho is another longtime gun writer and self-described gun nerd. He explains why copper bullets perform well in videos he posts on his Ron Spomer Outdoors YouTube channel. In a video about TSX bullets, Spomer shares photos of slugs fully expanding after striking an apple and a cherry tomato. He also shows a mushroomed TSX bullet in .280 Ackley that he recovered from a big whitetail, noting the 140-grain slug weighed the same after killing the buck.

“If you’re wondering if copper bullets work, I can assure you they work beautifully,” Spomer tells viewers.

Other shooting experts persuaded MeatEater founder and host Steve Rinella to resume shooting copper bullets after he experienced problems years ago with earlier solid copper versions. “I kept talking with other hunters and shooters who stay abreast of developments in the ammo world,” Rinella said. “So many of the gun nuts I hang out with were making the switch, and that helped convince me.”

In January 2020, Federal Ammunition introduced an exclusive line of MeatEater Ammunition in its Premium Trophy Copper lineup of polymer-tipped copper bullets.

“Honestly, I haven’t heard from a single person in my professional or social circles who’s had a bad experience with Trophy Copper,” Rinella said. “I like bullets that hold together because I like to minimize meat damage. I get great accuracy out of Trophy Copper, and the slugs mushroom beautifully without busting apart.”

Every-Day Endorsements If you don’t trust endorsements from gun writers or famous hunters, simply look up “copper vs. lead” on Google or YouTube. You’ll find well-documented reports and video demonstrations from every-day hunters and wildlife agency staff like Carl Batha, Phil Lehman, Scott Walter, and Dan Goltz of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Batha and Lehman tested and compared several copper and lead-core bullets in their .270 and .308 rifles for accuracy, consistency, and fragmentation in 2010. Goltz and Walter replicated the study in a 2020 video.

Batha and Lehman analyzed bullets fired into ballistic media, telephone books, and large water jugs. They proved to themselves that copper bullets outperformed “all the various incantations of lead bullets.” He also found that copper bullets allow hunters to use lighter-weight slugs to reduce recoil, and that they expand well at low or high speeds.

No matter how important those factors, some hunters remain skeptical about lead toxicity, especially if they process their own venison. They also distrust researchers’ objectivity regarding scavengers and gut piles.

Towsley, meanwhile, considers no-lead laws and mandates “sadly misguided.” He prefers letting hunters decide which bullets to use. So does Keith Tidball, a professor at Cornell University’s Department of Natural Resources in New York. Tidball notes that government bans on DDT and lead shot for waterfowl hunting helped the state’s bald eagle population rise from one nesting pair in 1976 to 350 pairs in 2018.

“During all that time of record growth in eagle numbers, lead ammunition was, and still is, being used for hunting deer and small-game,” Tidball said.

Tidball also thinks critics should not demonize ammunition manufacturers. After all, ammo companies have provided $11 billion to state wildlife agencies through excise taxes imposed by the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act, aka Pittman-Robertson, a law the industry helped craft and pass in 1937. No other group comes close to matching that financial support.

Tidball further notes that large hunter-based organizations like the National Wildlife Federation helped persuade the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to ban lead shot for waterfowl hunting in 1991 after a federal study estimated 1.6 to 2.4 million waterfowl were dying annually after swallowing spent lead pellets. Tidball said hunters want healthy wildlife but prefer to address “the lead-bullet question” through collaboration, education, and rigorous science; not government-imposed ammo bans like California’s.

Clausen, however, said it’s unrealistic to wait until entire wildlife populations are declining before acting to further restrict lead.

“Wildlife management has never been strictly about population-level management,” Clausen said. “For example, most states prohibit hunting big game with .22-caliber rimfire rifles. Is that because they have scientific evidence of population-level impacts? No. It’s because we have ethical and moral responsibilities to kill individual animals cleanly and quickly, and prevent waste of a natural resource.”

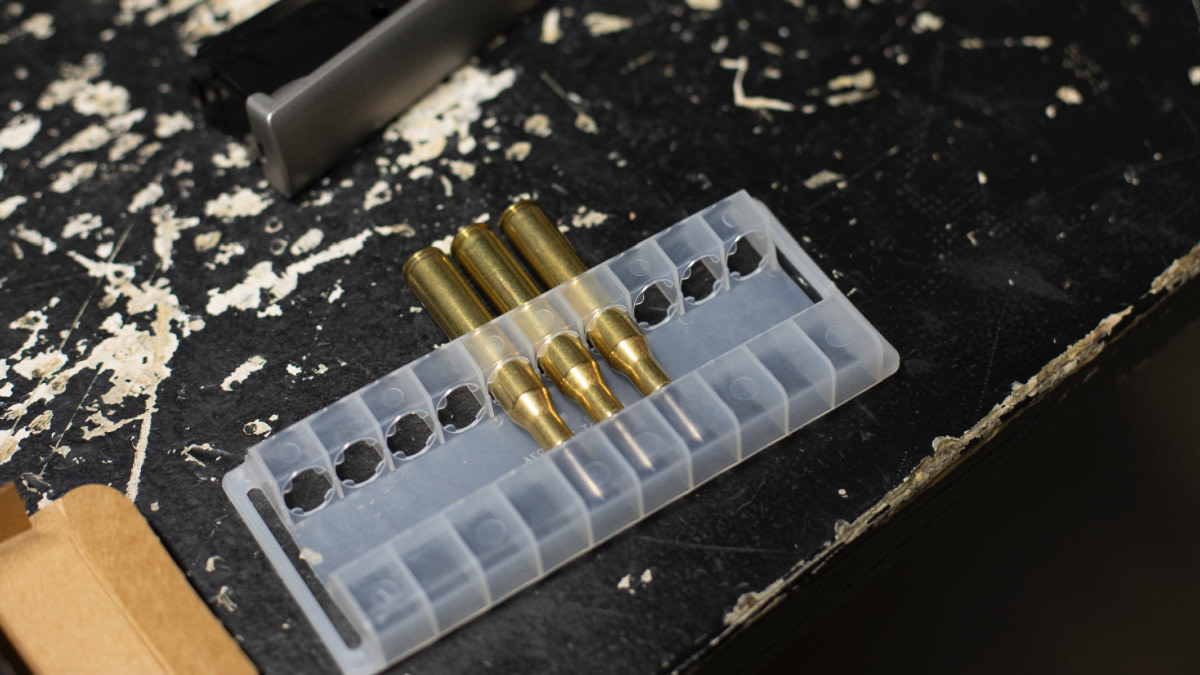

Growing Awareness Even so, hunters today seem increasingly aware of second-hand lead poisoning in avian and four-legged scavengers. In mid-October, for example, I posted photos on Instagram and Facebook of three all-copper slugs, one lead/copper bonded slug, and one partitioned lead/copper slug I recovered from deer or elk. I mentioned nothing about possible lead contamination in my self-processed venison or in gut piles left in the woods. I simply said all five bullets worked great, and asked readers why or why not they shoot copper bullets.

I received 51 responses overnight, 18 on Facebook and 33 on Instagram. Not one respondent bad-mouthed copper bullets. Most praised specific attributes like accuracy, low meat loss, and easily-followed blood trails.

What about food safety and environmental concerns? Six of the 18 Facebook respondents said they switched to copper bullets to ensure lead wouldn’t contaminate their venison or gut piles. On Instagram, six of the 33 respondents mentioned lead-contamination risks. My poll wasn’t scientific, of course, and it’s possible some respondents simply assumed I knew “getting the lead out” was their primary motivation.

Dollars and Cents Several respondents also justified the higher prices of copper bullets, which typically range from $44 to $55 for a 20-round box. That’s roughly twice as expensive as bargain-priced “cup-and-core” copper-jacketed lead bullets, but it’s comparable to prices for premium bonded or partitioned lead-core jacketed bullets.

“All-copper seems like the responsible path, given their performance and insignificant cost differences,” one commenter said. “I’m also happy with the accuracy.”

Another commenter raised the idea of only using copper bullets for sighting in and hunting.

“I use mainly Barnes but also Trophy Copper. Their performance and health/environmental benefits on scavengers are worth the minor cost increase over quality lead bullets,” they said. “I use lead for practice, and then shoot four to five copper bullets to verify point-of-aim. That makes a box of 20 lasts two to three years.”

Ryan Hutley of Michigan echoed that approach: “I’m not buying copper bullets to stockpile for the apocalypse,” he said. “I buy them strictly for hunting.”

Despite mostly favorable reviews, not all hunters in my poll expected to switch to copper bullets or resume hunting with copper this fall. Although some hunters found copper bullets in nearby stores, most noticed ongoing shortages no matter the price, brand, or calendar.

One reader wrote: “I love them, and would like to use only Barnes or Federal Premium all-coppers the rest of my life, but it’s hard to find them right now.”

And yet another respondent felt nervous watching his supply dwindle: “I’m glad I made the switch, because their performance on deer has been way better than the [cup-and-core] bullets I shot previously. Now if I can only find some.”

Conclusion Consider Clausen’s friend who scorned copper bullets and gave him four boxes of TSX rounds in 2009. When they crossed paths after the 2010 deer season, the man declared himself a copper convert. Clausen asked him why.

“The ballistics are great and the killing power is awesome,” his friend replied. “Besides, this lead thing is serious. We can’t let anti-hunters dictate the discussion.”