The term “wildcatter” is most frequently used to refer to oil prospectors from the late 19th century who drilled exploration wells in search of new petroleum fields. But the word also refers to another group of optimistic entrepreneurs, folks who hope to strike it rich (or at least become famous) in a much different way.

“Wildcat cartridges” are firearm cartridges that haven’t been reviewed by a safety association or adopted by a big ammunition manufacturer. They’re developed in garages, basements, and workshops, and they’ve driven a good deal of ammunition innovation over the last 100 years. If you hunt with a long-range, high-velocity cartridge, you can probably thank a wildcatter.

A Brief History

Americans have been tinkering with cartridge designs ever since the first metal-cased integrated cartridges hit the market in the mid- to late-19th century, Fed Zeglin, author of “Wildcat Cartridges,” told MeatEater.

“As soon as a guy with a little bit of mechanical understanding saw that he could neck up or down a cartridge, they’d go to their local gunsmith and say, ‘Hey, here’s what I want to do,’” Zeglin said.

Zeglin identifies the first wildcat as the .25-20 Single Shot developed by gun writer J. Francis Rabbeth around 1882. As metal-cased cartridges and smokeless powder became more common, wildcatters ran with a variety of .22- and .25-caliber loads. The .25 Krag, for example, is one of the oldest and most popular of the early wildcats, developed around the turn of the 20th century.

The wildcat game didn’t begin in earnest until after World War I, “when we saw what the German snipers could do with their long-throated cartridges that we would never think about producing here in the States,” engineer Dave Kiff told MeatEater.

Kiff has developed and consulted on numerous successful wildcats for Pacific Tool & Gauge, and he studied under the legendary wildcatter P.O. Ackley. He says that wildcatting started to take off when American soldiers returned home after four years of avoiding German Mauser rifles and their 8mm cartridges.

Benchrest competitions, varmint hunts, and turkey shoots gave wildcatters a proving ground for their new cartridges, and Zeglin calls the mid-20th century a “wildcat renaissance.”

If that’s the case, you might consider P.O. Ackley a kind of Michelangelo.

Most hunters are familiar with the .280 Ackley Improved, which became a factory production cartridge in 2006. But P.O. Ackley developed dozens of wildcat cartridges in his lengthy and successful career, and his name is among the most famous in the wildcatting world.

“The most popular wildcats of all time started mainly in the 1950s by P.O. Ackley,” Kiff said. “Mr. Ackley was the master of making something work and perform, bringing in tighter throats and better groups.”

Ackley’s improved cartridges could be crafted by firing a commercial case in a custom-made chamber and then reloading the resulting case. His first wildcat cartridge was the .219 Zipper Improved, which he released in 1938. From that year until his death in 1989, Ackley invented dozens of improved wildcats along with more complex original designs.

Many of Ackley’s improved designs feature a sharper shoulder angle and produce higher velocities. He improved on many of the most common cartridges, including the .30-06, .30-30, and .270.

Ackley wasn’t the only wildcatter in the U.S., of course. Roy Weatherby, founder of the rifle manufacturing company that bears his name, got his start as a wildcatter producing cartridges that moved faster and hit harder than anything commercially available.

“His passion for wildcatting stemmed from the need for high velocity. That’s how our organization started, trying to get bullets moving faster,” Adam Weatherby, Roy’s grandson, told MeatEater. “The premise of his wildcatting was to get a quicker, more humane kill due to the shock of the bullet’s velocity. It also allowed for the bullet to shoot flatter.”

Today Weatherby, Inc. is best known for its high-quality hunting rifles—but the company made its name on the back of Roy Weatherby’s cartridge designs.

Roy once spent an entire night tracking a deer he injured on a hunt in Utah, Adam told us. Even though he had no prior ballistics or engineering training, the experience gave him the desire to make a faster-shooting cartridge to take game more effectively.

Weatherby’s first design was the Weatherby Rocket, which came out in 1943. After that came the now-legendary .257 Weatherby Magnum, which was followed by nine additional Roy Weatherby cartridges that are still in production today. Many of those original designs were made for the Mauser action.

Like most wildcatters, Weatherby adjusted the geometry of bullet cases to achieve greater velocities. He rounded the shoulders of existing cartridges to allow for more powder capacity and change the burn rate of the powder, Adam explained. Today, Weatherby boasts the fastest cartridges in 6.5mm, .30 caliber, .338 caliber, .257 caliber, .240 caliber, and .243 caliber.

Most wildcatters aren’t as lucky as Weatherby, who created opportunity for bringing many of his wildcats to the wider market. But many of today’s most popular cartridges began their lives as wildcats. These include, according to Frank C. Barnes in “Cartridges of the World,” the .17 Remington, .22 Hornet, .22-250 Remington, .243 Winchester, .244 Remington, .257 Roberts, .25-06 Remington, .280 Remington, 7mm-08 Remington, 7-30 Waters, and .35 Whelen.

Wildcatters are responsible for “major advances in our knowledge of internal ballistics,” according to Barnes, and it’s unlikely we’d have as many high-velocity options as we do today without the innovative spirits of men like Ackley and Weatherby.

Why Wildcatting?

They don’t do it for the money. Barnes points out that wildcat designs are incredibly difficult to monetize because they must be tested in the field for many years to prove their efficacy. By that time the design is general knowledge and it’s difficult to maintain control of that intellectual property.

Many wildcatters want to push the limits of how fast a bullet can go, and that was an especially attractive goal before high-velocity cartridges became widely popular.

Other wildcatters just want a cartridge meant for a specific action or a specific purpose, Zeglin said. Some calibers aren’t offered in certain types of action, so a wildcatter might want to develop their own cartridge to fit.

Zeglin mentioned a state fish and game agency that wanted to control the population of a certain species on the edge of town but didn’t want the “little old ladies” to know about it. So, they created their own subsonic cartridge that could be used with a suppressor and wouldn’t be heard by the town’s residents.

Adam Weatherby said his company built the 6.5 RPM to deliver magnum performance out of a short-action mountain rifle.

“There’s a lot of lightweight rifles, but on most lightweight rifles you’re going to sacrifice ballistics,” he said. “We wanted to create the lightest, fastest production rifle there is. I wanted a sub-5-pound rifle with magnum performance. The 6.5 RPM resulted from that.”

Weatherby’s new cartridges may not technically be “wildcats” because they are produced by a large company, but the idea is the same. Wildcatters create a cartridge because they see a need and want to fill it.

But sometimes they just want to put their name on something. Both Zeglin (who has developed 14 wildcat loads himself) and Kiff mentioned that ego can be a motivator for wildcatters. Becoming famous like P.O. Ackley or Roy Weatherby is an attractive proposition, and lots of budding ballistics engineers think they can improve on the cartridges currently available.

The truth is, like in most industries, it’s difficult to be truly innovative. More velocity doesn’t always result in better performance. And experimenting with gunpowder can sometimes result in tragedy.

Kiff recalled a wildcatter who had tried to load a .17 caliber projectile in a .22-250 Ackley Improved casing and another who tried to neck down a .50 BMG to 7mm. Both experiments resulted in catastrophe.

So, You Want to Shoot a Wildcat

That doesn’t mean it’s not worth trying. Zeglin said his line of Hawk wildcats don’t bear his name in part because he was motivated by the fun and the challenge of the process.

If you have an idea for a wildcat, Kiff told us he’s willing to help get the drawings made, the brass ordered, the reamers, gauges, and bolt manufactured, and the dies designed. It’s not the type of project we have the space to outline in full, but Kiff assured us the process is much easier than it was in decades past. You’ll have to reload all your own ammunition, of course, and it’ll cost you a pretty penny.

For a fantastic overview of how this process might work, check out this podcast episode from Vortex. They recently designed and tested a wildcat called the 6.5 BC and recorded the entire adventure.

If that looks too intimidating, you can still shoot a preexisting wildcat cartridge without much technical expertise. Custom barrel makers offer wildcat chambers, and a knowledgeable gunsmith can install that barrel on an appropriate action and fit that action to a stock. Once you have the rifle, you’ll need to order a set of custom dies to reload ammunition since you won’t be able to find it in stores.

You’ll spend quite a bit more than you might for a factory rifle in a production cartridge, but by the end of the process you’ll have a super accurate rifle in a cartridge tailor-made for your specific purpose.

If you’re looking for ideas for your next whitetail hunt, Zeglin recommends looking for wildcats in .243 caliber, 6.5mm, or 7mm.

Final Round

The wildcat world is much broader than we’ve had the chance to cover here. We didn’t get to discuss some other famous wildcatters like Harvey Donaldson, and we didn’t even touch on the vast majority of famous cartridges. But it’s a fascinating topic if you’re interested in cartridge development, the history of firearms in the United States, or groundbreaking American inventors. We owe more than we realize to these pioneering folks, and their stories deserve to be told more often.

For further reading, check out Zeglin’s “Wildcat Cartridges,” Richard F. Simmons’ “Wildcat Cartridges,” and “Wildcat Cartridges I and II.” For a biography of P.O. Ackley, check out Zeglin’s “P.O. Ackley.”

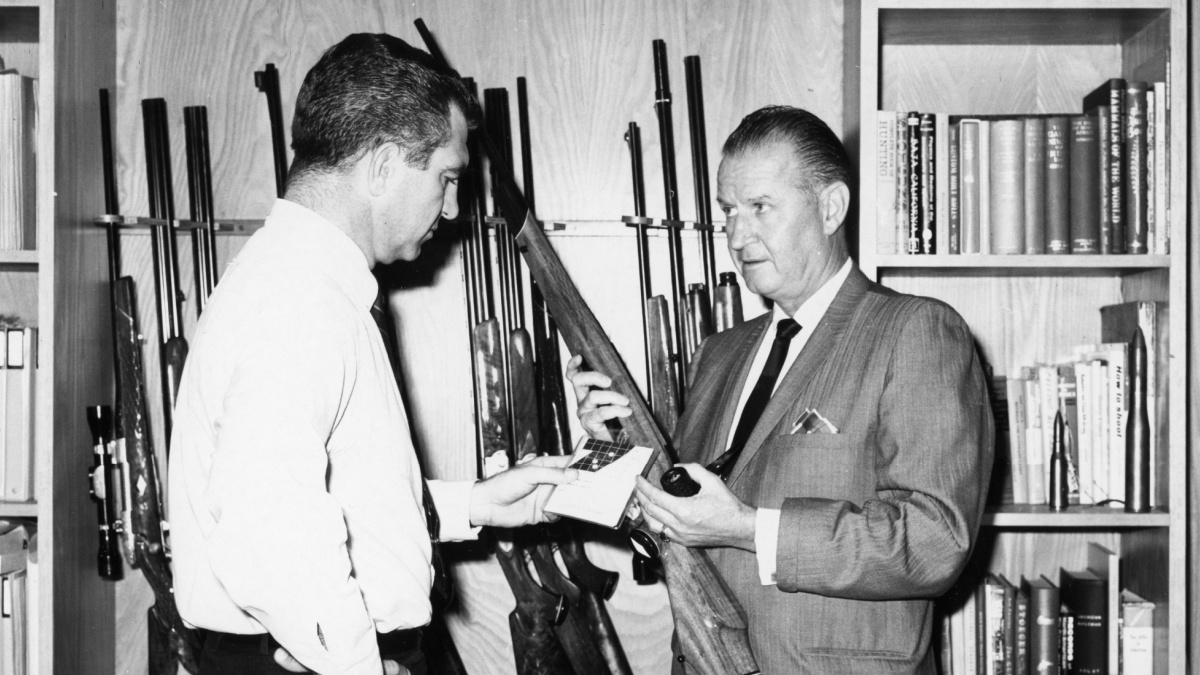

Images of Roy Weatherby via Weatherby.