We’ve said it before and we’ll say it again-wildlife biologists and researchers provide outdoorsmen and women with an incredible array of information that can be used to make them better hunters. It’s a sad truth that too many of us don’t take advantage of the all the tools these experts make available to us. All you need is a computer and internet service.

Information that can be used to help you plan future hunts is readily available. Many states provide GIS mapping technology where hotspots can be found by searching for recent wildfire activity or road closures. Biologists publish data on population trends such as buck-to-doe ratios or winterkill rate which can be just as valuable. Other research might predict pheasant or quail populations based on chick survival rates following a particularly wet spring or a very dry summer. A study on how a deer’s gut bacteria changes from fall to winter, and in turn how their foraging changes seasonally, could help a late season hunter find preferred sources and the best hunting spots. Other behavioral research is also a valuable tool. Recently, a long-term capture and collar study from the University of Alberta showed how elk avoid hunters. This study showed that cow elk that survive ten hunting seasons become almost “bulletproof” and some of their survival tactics are learned over time not just instinctual, genetically inherited traits.

Even if this type of capture and collar research didn’t take place in your home state, it can still be incredibly helpful. For example, recent studies on two very different deer, a mule deer doe in western Wyoming and a whitetail buck in central Pennsylvania documented notably disparate movement patterns over an extended period of time. This information can be applied to both species in a way that’s useful to hunters wherever mule deer or whitetails live.

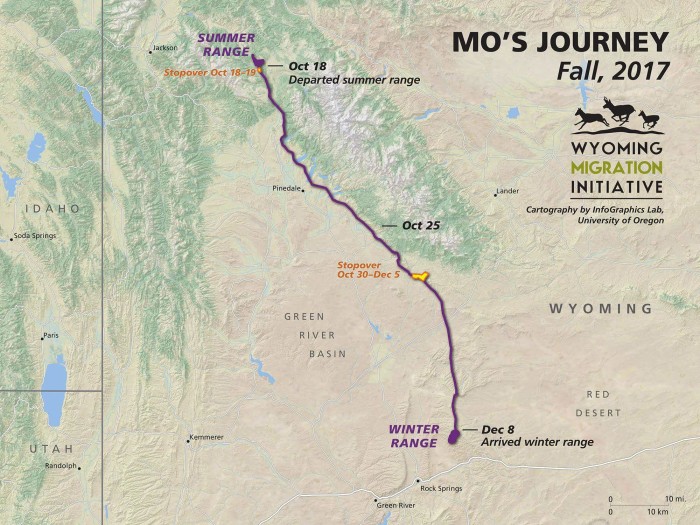

The first study focused on long-term movements of mule deer in western Wyoming during the fall. Over the past few years, The Wyoming Migration Initiative has been studying an important mule deer migration route that wasn’t well understood in the past. Mule deer in this part of Wyoming migrate well over one hundred miles from summer high country habitat to low elevation desert winter range. Last fall, they collared a mule deer doe they named Mo and documented her travels. Over the course of the migration, she moved south along the Wind River Range near Jackson, traversing the foothills above the Green River until she departed the mountains and settled in for the winter in the Red Desert near Rock Springs. While the distance and difficulty of the migration is a fascinating story, the information Mo’s journey provides can be used by hunters to predict where they can find mule deer throughout hunting season. After spending the summer in alpine summer range, Mo was constantly on the move southward throughout October but then stopped well short of her wintering area for a few weeks before moving on. Don’t expect mule deer to remain in the same area for long in the fall. However, during periods of warm weather without significant snowfall, mule deer may hang up at higher elevations with good food sources. Last November, Steve and I each killed our Colorado mule deer bucks at much higher elevations than expected for that time of year. The weather had been mild for weeks and the majority of the deer were hanging out where you’d expect to find them in September. But inevitably, weather will force them to migrate and mule deer may travel several miles in a single night. Hunters should be prepared to cover ground to find them.

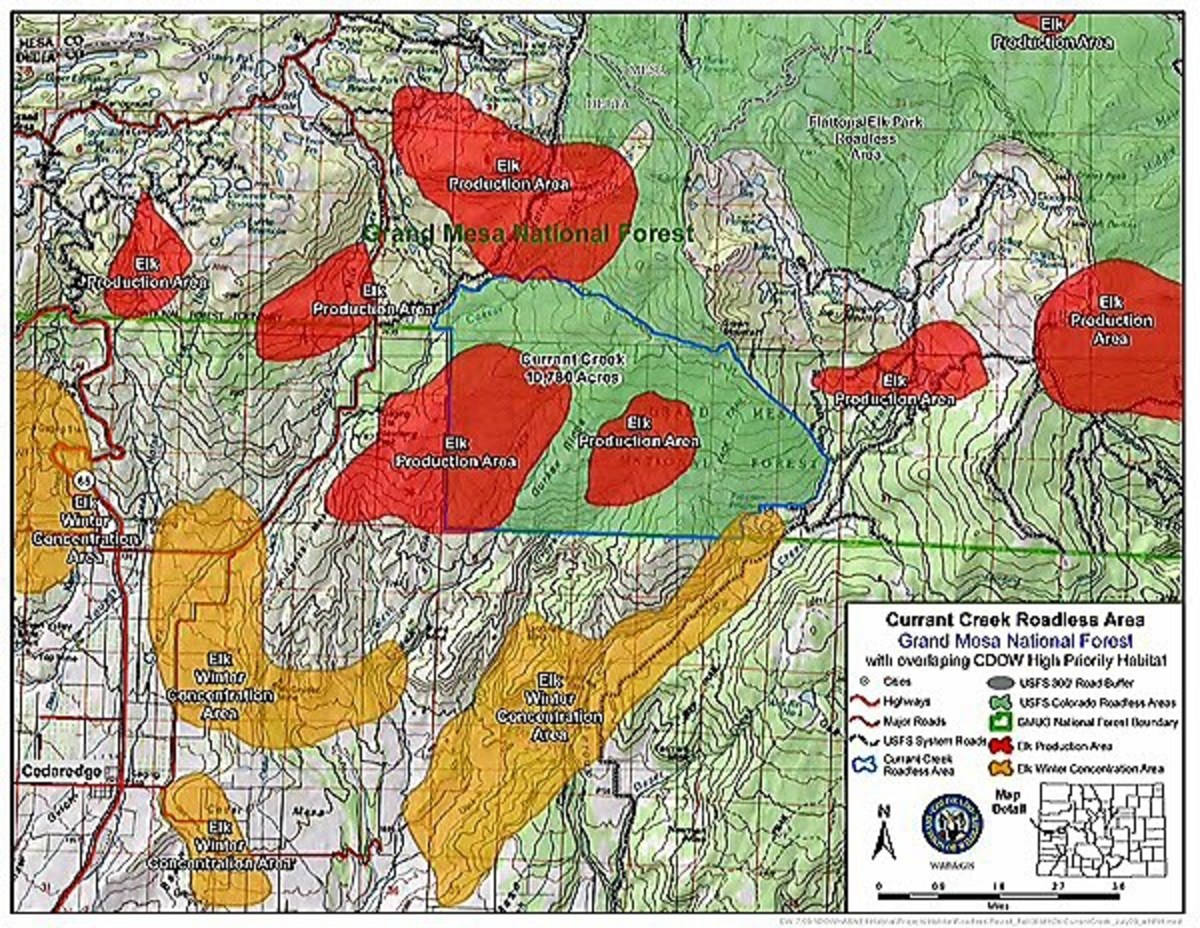

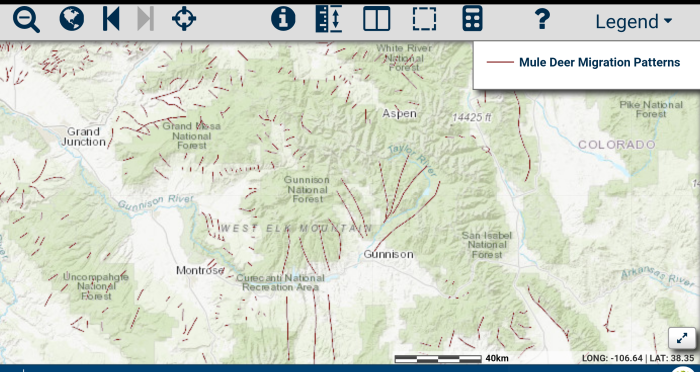

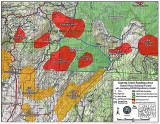

Mo’s migration behavior illustrates a general pattern for deer in that part of Wyoming and I was curious if the mule deer here followed a similar pattern, even if it might be on a smaller scale. And further research on the state’s Parks and Wildlife website, in the form of a species-specific GIS mapping layer, proved that to be the case, although the timing is weather-dependent. I was able to find not only large-scale migration patterns but also narrow corridors mule deer used in specific drainages. That is pretty valuable information for a mule deer hunter.

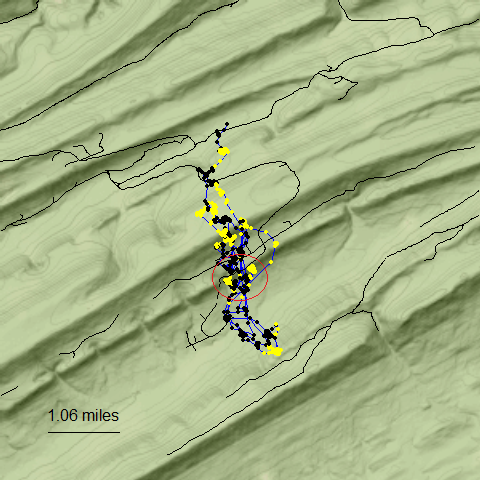

In the second example, Penn State University’s Department of Ecosystem Science and Management conducted a three-year study that tracked a mature whitetail buck’s daily movement patterns. This GPS tracking device study collected waypoints every few hours that hunters can use to pinpoint big buck hideouts throughout whitetail country. Buck 8393 lived primarily on heavily-hunted public land and managed to survive several hunting seasons before he was eventually killed by a hunter. 8393 sometimes bedded right next to roads, which should make you wonder how many deer you’re walking past on the way to your stand. Even more interesting is the fact that this deer avoided hunters almost like a paranoid elk would. He used the steepest topography in his territory, 50 percent slopes, as a sanctuary during hunting season. Escape, if necessary, was simply a matter of using the topography just like elk often do. If surprised from above, 8393 could head downhill in a hurry. Or, if hunters attempted climbing the slope below, the buck could quietly slip out of sight over the top of the ridge. But unlike an elk that might cover several miles in a day, 8393’s core territory was a small chunk of ground. Additionally, he rarely moved during the day while rifle season was open. These survival tactics should be an eye-opener for whitetail hunters, especially those who doubt the existence of mature bucks in their hunting area.

Even though this buck lived in on public land in Pennsylvania, this study points me in the right direction the next time I’m hunting public land whitetails in the hills of western Nebraska during the November rifle season. I’ll concentrate my time on or near the steepest timbered ridges. And even if I spook a big buck, contrary to conventional thinking, he’s likely to return because he knows the area so well that he feels safe there. The proof lies in three years worth of data that shows mature whitetail bucks are creatures of habit.

This type of information can be as valuable as a week-long scouting mission. With a little searching, you’ll also find things like public lands access, draw odds, and success rates. There’s even fee-based internet hunting services that sell this kind of information. But it’s important to understand the information they’re providing is all available for free on state fish and game agency websites- if you’re willing to put in the time finding it. What isn’t available from these subscription services is wildlife research data that will help you develop a better understanding of the behaviors and habitat of the animals you’re hunting. And don’t limit your searching to state fish and game agencies. There’s plenty of other sources available from federal agencies, university funded wildlife studies, and hunter and angler conservation groups.

Brody Henderson

Brody Henderson is a writer, hunter, fly fishing guide, wilderness production assistant for the MeatEater television show, and MeatEater’s editorial contributor

Conversation