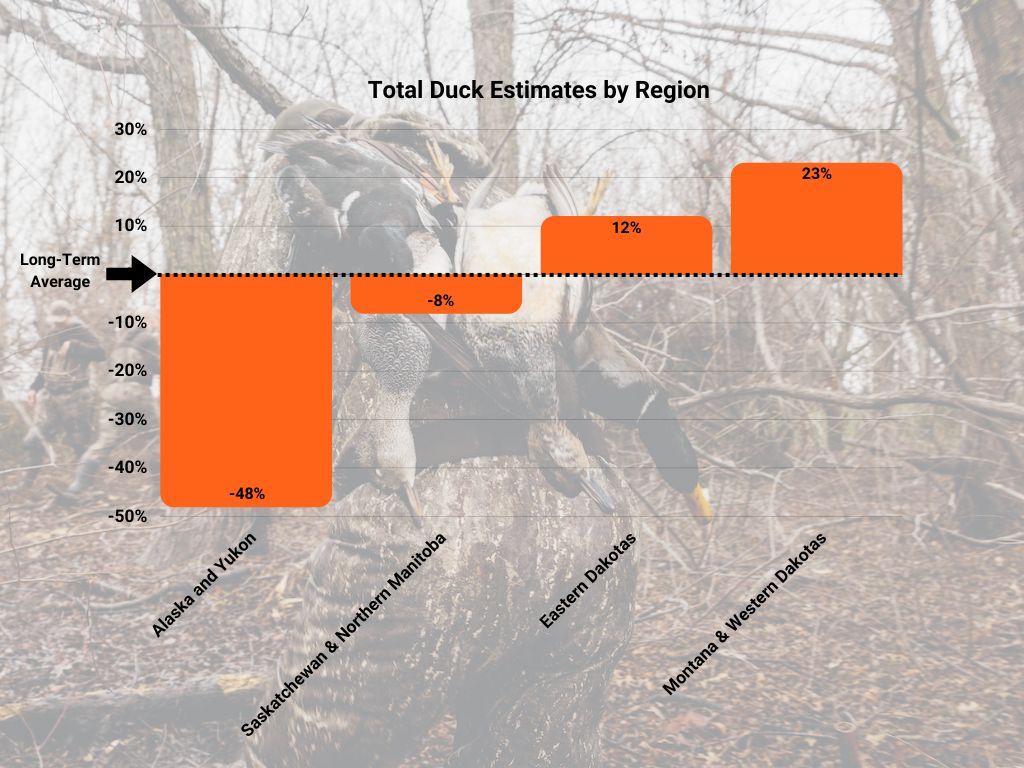

Last week, the US Fish and Wildlife Service published an annual Waterfowl Population Status Report, outlining declining duck and goose populations across North American flyways.

This spring, American and Canadian federal biologists flew transects throughout the north-central US, Alaska, and Canada to record waterfowl distribution and abundance. In all, the numbers reported in the survey are based on the data they collected but extrapolated to 2 million square miles of flyways and breeding grounds.

Overall, duck and goose populations are down. But that doesn’t necessarily mean your waterfowl season is shot down already. Keep reading for a summary of key survey data, a discussion of environmental factors, and what it means for waterfowl hunters this year.

In terms of species, mallards and northern pintails took the biggest hits, at 23% and 43% below their long-term averages, respectively. However, pintails are at a 24% population increase from 2022, demonstrating the time population rebounds require and the necessity of yearly monitoring for adequate management.

Geese are also experiencing a downward shift in population counts. Biologists in the study noted the effects weather can have on various species in different geographic regions. For example, persistent snow cover makes nesting more difficult for some Canada goose populations. When spring snow sticks around a bit longer up North, numbers tend to plummet. Similarly, major springtime flooding events during the nesting season will also impact the reproductive success of geese located further south.

Drought In the Prairie-Pothole Region

Another important metric in the report is the “total pond estimate,” which is a reflection of how wet the prairie-pothole region of the Dakotas and Canada is. This year, the estimate is 5 million ponds, which is 9% lower than 2022, and 5% below the long-term average.

“We’re on year nine or ten of there being some degree of drought across the prairie landscape,” Dr. Mike Brasher, a senior waterfowl scientist with Ducks Unlimited, told MeatEater. “It’s been a long time since the entire prairie landscape across the US and Canada has been wet.”

Recently, 2021 was an extreme drought year; however, no survey was conducted due to the pandemic. Last year saw an increase in wetness, especially in the Dakotas, leading biologists to believe duck numbers might be on the upswing this year. “Decades of science have demonstrated that duck numbers and duck production are strongly correlated to the number of ponds in the pothole landscape,” Brasher said.

But surprisingly, survey numbers were lower than anticipated. Based on harvest data, biologists know that last year was a good production year. According to Brasher, however, it can take a couple years for populations to rebound once wetlands are recharged. And even then, it takes continued, annual wetting to reach maximum productivity.

For that to happen, a number of climatic factors have to align. This year, for example, the Dakotas received abundant snowfall, but it melted out rapidly. Then, on the Canada side, the landscape didn’t receive much winter precipitation and remained parched into the spring and summer (remember those early-June wildfires in Canada?).

A little further north, though, in the boreal forests of Canada, conditions have remained relatively consistent and stable for a number of years. Boreal landscapes don’t see the swings that the prairie exhibits, but on the flip side don’t have nearly the productivity potential in booming, wet years.

In short, populations are down but still within a healthy range. “We’re not concerned about a one-year decline, and we don’t make conservation decisions on one year of data,” Brasher said. “We know ducks haven’t lost their ability to reproduce, and they can still be highly productive when environmental conditions are favorable.”

Impacts on Hunting

The USFWS sets seasonal regulations based on data from the annual survey, but the data informs the following year (so this year’s survey will be used to guide 2024-25 regulations). Another key component of regulation-setting is age-class data obtained from hunters during the prior season.

Last year, for example, saw an uptick in young birds harvested, which means this year could see an increase in adult bird harvests as that year-class had another season to grow.

“It’s important that people not read too much into these numbers,” Brasher said. “It’s valuable to follow along and understand what’s going on with the ups and downs of waterfowl populations… but I wouldn’t let these numbers dictate if I’ll get fired up about waterfowl hunting this fall.”

He also wants to remind people that conservation is a long game. While harvest quotas might be based on survey numbers, management is a game of years or decades, and long-term averages are just that—long term.

Population numbers and habitat are just two pieces of a larger puzzle that will influence hunter success this fall and winter. Seasonal conditions, migratory behavior, and good ol’ fashioned luck could still result in a phenomenal season.

But know, however, if a “honey hole” doesn’t pan out this fall, a small decline in bird numbers could make for a great excuse.

To check out the USFWS report for more details on specific species and geographic regions, click here.