Just aim for the vitals, right?

After all, the anatomy of deer has stayed pretty consistent for millions of years. In fact, fossil records show that antler-shedding ancestors of our modern deer were on the scene some 15 to 30 million years ago. While they’ve gone through plenty of changes since then, the location of their heart and lungs seems to have stayed relatively static.

It really doesn’t matter to us, as modern hunters, the anatomical layout of the precursor deer species that dodged ancient, long-extinct predators. We know how modern whitetails are put together, and that means we should know where to shoot them. And we do, mostly. But exact, lethal, aiming points change with animal orientation and whether we are clutching archery equipment in our hands or a deer rifle.

Where to Shoot a Deer With a Bow

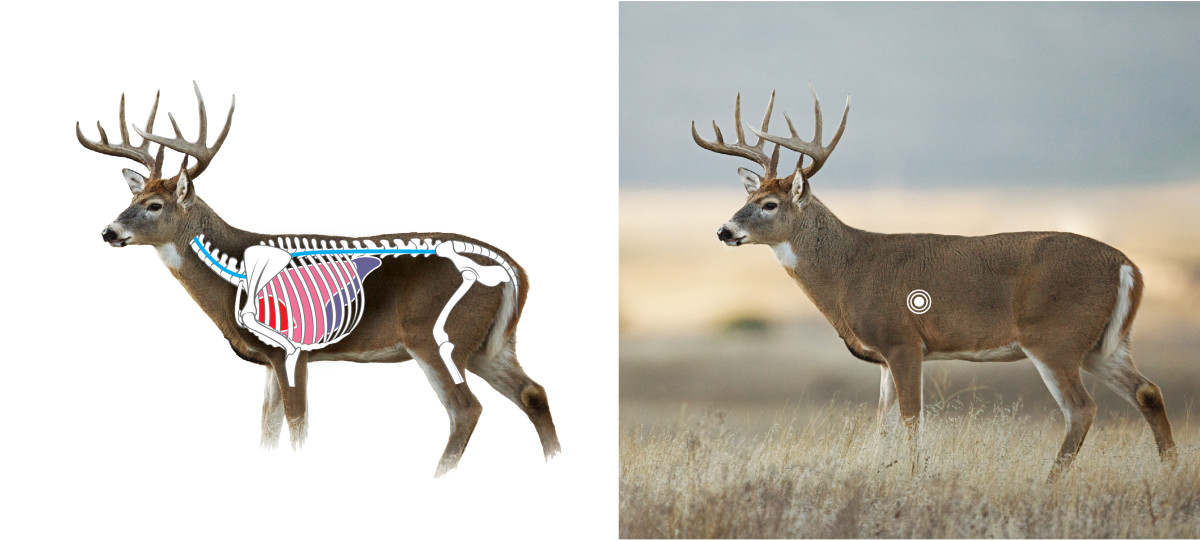

The goal with every shot we take should be to take out the heart, the lungs, or some combination of the two. This is easiest to understand with perfectly broadside deer.

Look at the shoulder blade and the last rib. Somewhere between those two lies everything you need to hit in order to do your job as an ethical hunter. The catch is that the shoulder blade, even with the retro-now-modern push to shoot heavy arrows and fixed-blade heads, is a no-no. Conventional shooting advice often preaches the right-in-the-shoulder-crease shot placement, but that leaves you no margin for error.

A better bet is to understand the space the lungs take up behind the shoulder and the ribs. You have room to aim 4 or 5 inches back from the shoulder crease, which increases the margin-of-error on a broadside deer. A few inches forward, no biggie. A few inches back, and you’ll clip the tail-end of the lungs or the liver, or both.

How high to aim is a different story. To think about this correctly, draw an imaginary line through the main part of the deer’s body, like you’re creating an equator between the northern and southern hemisphere.

That halfway point will put you in the sweet spot, but it’s a good bet to cheat your aim point down a few inches. If your deer drops at the shot, which is very likely, you’ll hit it center mass. If it doesn’t, you will still take out everything you need to.

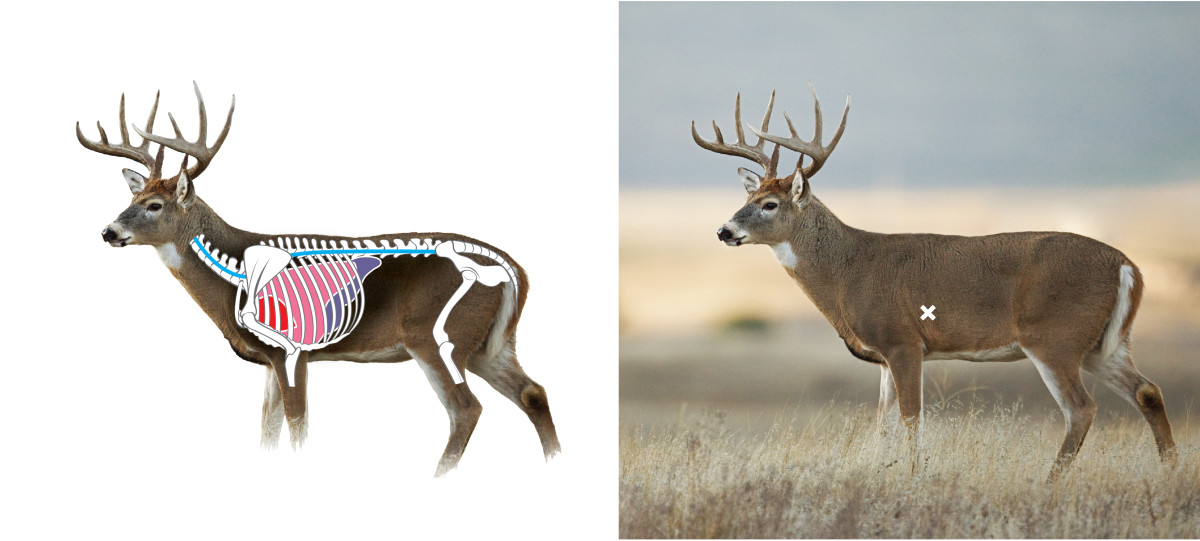

What about a deer that doesn’t pose up perfectly while you’re at ground level? Then you have to adjust your point-of-impact accordingly and decide if the angle will still allow for a clean path to the vitals. Quartering-away deer, which are my favorite, give you the best option here.

As long as the angle doesn’t get too severe, you can walk your pin back a few inches to ensure a lethal hit. If you find yourself having to aim dead center for the liver to get the far lung, the angle is as far as you want to mess with, and it’s probably better to wait.

A quartering-to deer is a riskier proposition because you’re always dancing with the shoulder blade. Slight quartering-to, by a few degrees, will leave you room to deflate the lungs. But remember, any angle that forces you to really hug the shoulder, or worse, attempt to shoot through it, is generally a bad idea. Again, I know there are heavy-arrow proponents pushing these shots, but that’s with a lot of confidence in specific setups, and not great advice for the general hunting population.

Where To Shoot a Deer With a Gun

Gun hunters have a simpler proposition when it comes to where to shoot a deer. The shoulder is a nonissue even with pea-shooter calibers, and that means that if you can put a bullet where it should hit both lungs or the heart, you’re good.

Unlike archers, gun hunters can do just fine hugging the crease of the shoulder and holding right at the equator between the top and bottom of the deer.

With quartering-away angles, the same rules apply as they do to bowhunters.

Quartering-to shots allow for some more leeway because you can aim directly at the shoulder and you should be able to make it right through to the good stuff.

This is mostly personal preference, but some hunters prefer the shoulder shot when they carry a rifle, shotgun, or muzzleloader into the woods. This shot, done correctly, anchors your deer in place and alleviates the need to blood trail. The downside is that you reduce your margin of error toward the front of the deer, where a non-lethal hit can occur.

A better bet is to forget about breaking the deer down on the shot and instead focus on hitting the vitals. If you only punch ribs and vitals, the odds of trailing your deer less than a football field’s distance are extremely high, and you don’t run the risk of a nonlethal hit from pulling the shot left or right by a few inches.

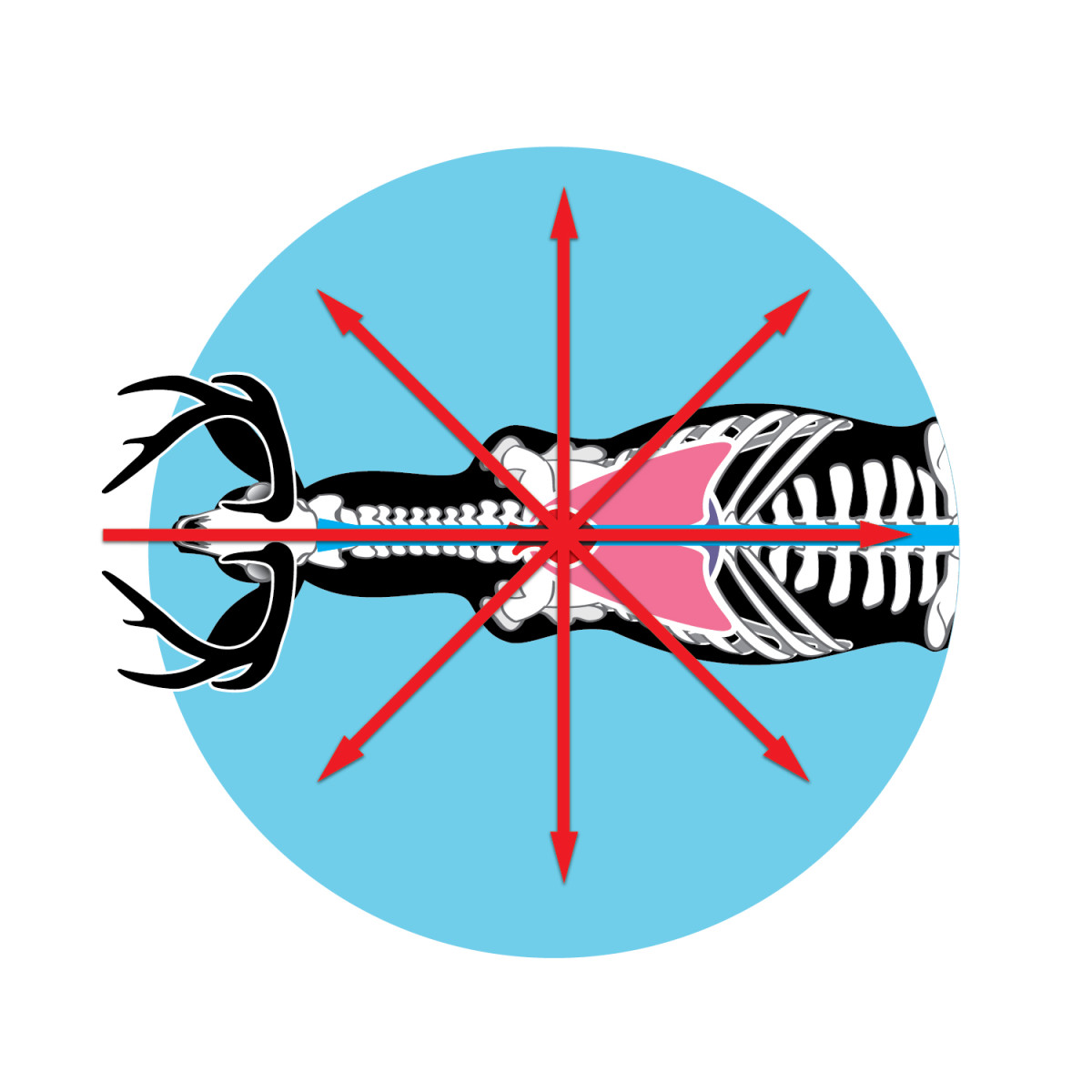

Envision the Ideal Exit Wound

The best method for making good on any shot, regardless of weapon choice, is to consider exactly where the entrance wound needs to be to create the ideal exit wound. This creates a point-A-to-B thought process that allows you to easily consider whether you should be able to take out the vitals or not. Seasoned hunters live by this exercise when they are considering their shot opportunities, and you should, too.

Simply start with perfect exit wound, and reverse engineer the route your arrow or bullet would have to take to get there. If the entrance is still doable, then the light is green. If there is nagging doubt, or the realization that the angle is too steep or too risky, hit the brakes and wait.

The Three Shots You Should Never Take

We owe it to the deer to try to kill them quickly and humanely. This means that certain shots are just a no-go, no matter how many YouTubers espouse their benefits, or how bad we want to put a buck on our wall. Here are three you should pass on, no matter what.

Texas Heart Shot: If a deer is facing away from you, or angled hard enough where you’re getting a better look at his tail than his side, don’t shoot. Sure, if you get one in him, he’s probably going to die. There are some major arteries, blood-filled muscle groups, and intestines located in the rear-end, but this is an ugly, dumb shot to take that very well could result in an unrecovered deer.

Full Frontal: The elk world is full of hunters talking about the frontal shot. This is because elk are mostly killed at ground level, and they are much bigger than whitetails. Most deer are killed from an elevated position, and weigh in at a quarter to a third of an elk. The margin for error on a frontal shot is small, the deer is almost guaranteed to be looking at you (obviously) and a slight miss on your point-of-impact equates to a huge problem with likely recovery.

Head Shots: Don’t. Just don’t. A deer’s head is a tiny target that moves often, and if you’re off by an inch or two it’s going to be a horror story. Blown-off jaws, or deer with arrows stuck in their heads, are not only horrible for hunter PR, but also testament to how we have some absolute dipshits in our ranks. If you are willing to take a head shot, do the rest of us a favor and sell your hunting gear to buy some golf clubs.

Graphics by Peter Sucheski.