A few years back, shortly after our family moved into a new home, I killed a cow elk in the federally designated wilderness area just a mile from my back door. It wasn’t until after I had notched my tag, quartered the elk and packed the meat down the mountain that I realized how lucky I was to live next to 44,000 acres of wilderness where I can hike, camp, fly fish for trout, and hunt dusky grouse, snowshoe hare, black bear, deer and elk.

I’m not the only one who can hunt those elk. After all, federal wilderness is public land, accessible for everyone to enjoy. That Colorado wilderness area can be hunted by anyone who is willing to buy a license and hike or ride in on horses. The same holds true in the 43 other states that contain wilderness areas, Wyoming being the one glaring exception.

There are over 110 million acres of federally designated wilderness in the United States that outdoor recreationists of all types, including big game hunters, are free to explore on their own. The only caveat is that motorized and mechanical travel is prohibited in wilderness areas while foot, horse and non-motorized boat travel is legal. These travel restrictions preserve the natural integrity and beauty of these truly wild places and, because they are managed for minimal human impact, wilderness areas provide clean air and water, important fish and wildlife habitat and outstanding fishing and hunting opportunities.

This has been the case since the Wilderness Society‘s Howard Zahniser wrote the Wilderness Act in 1964. Zahniser wrote the language of the law, but the idea that intact landscapes needed protection wasn’t a new one. Decades earlier, American conservation pioneers like Bob Marshall and Aldo Leopold, both of whom now have wilderness areas named after them, recognized the value of these places. When President Lyndon Johnson signed the act into law, the National Wilderness Preservation System officially ensured that all Americans would be granted access to publicly-owned expanses of wild lands unmarred by roads or development.

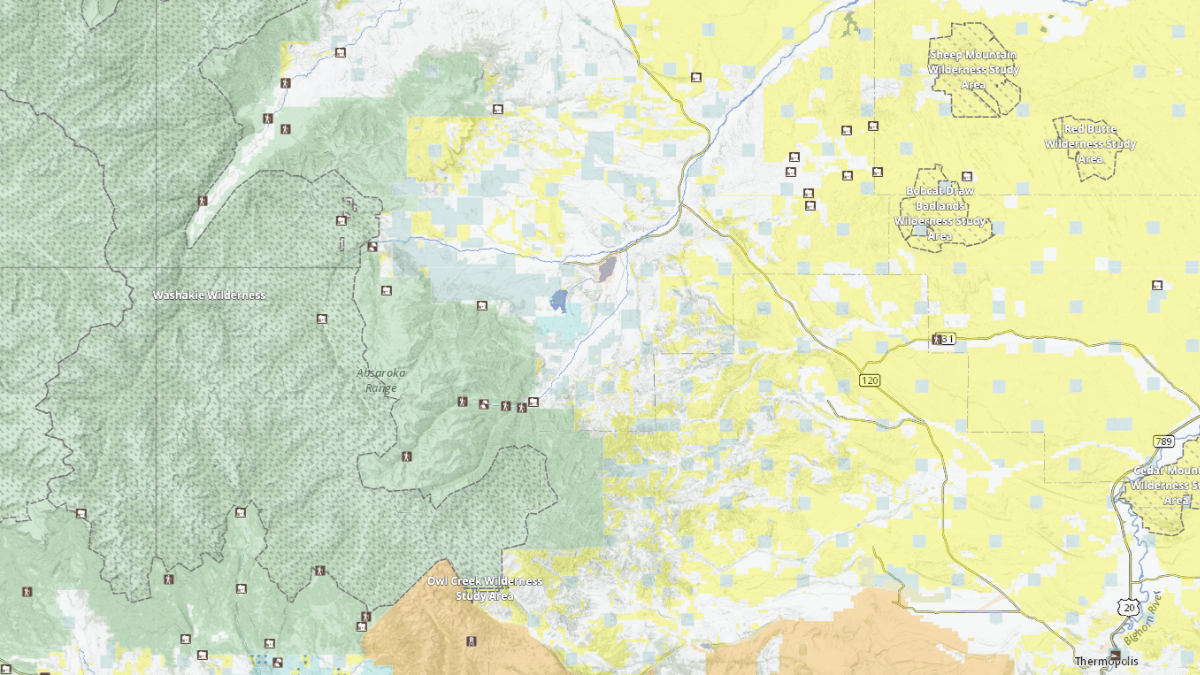

In Wyoming, that’s not the case for non-resident big game hunters. Wyoming is home to 14 federal wilderness areas totaling over 3 million acres of public lands, and for do-it-yourself, non-resident big game hunters, those 3 million acres of public land are off limits.

That’s right: Wyoming law prevents out of state big game hunters from accessing the same wilderness areas where day hikers, bird watchers, fly fishermen, mountain climbers and bird hunters can roam freely.

Wyoming statute says, “Nonresidents must have a licensed guide or resident companion to hunt big [deer, elk, moose, sheep, mountain goats] or trophy game [black bears, cougars, wolves] in federally designated wilderness areas. The resident companion will need to get a free non-commercial guide license from a Game and Fish office. The law does not prohibit nonresidents from hiking, fishing or hunting game birds, small game, or coyotes in wilderness areas.”

The foundation of this statute was laid long before any federally designated wilderness areas existed in Wyoming. In 1957, the state passed a law preventing non-residents from hunting high-profile big game animals like mule deer, elk, bear and bighorn sheep on federal and state lands without a guide. No such restrictions existed for hunting small game, coyotes or pronghorn antelope.

The law remained in place until 1973, when the Schakel v. State of Wyoming case found it was discriminatory to prevent non-resident hunters from accessing public lands administered by the federal government.

The court also determined the safety of non-resident hunters was not a legitimate basis for enforcing the law, stating, “An examination of the statute demonstrates that it can have little if any relationship to such objective. The dangers to a hunter of antelope would seem as great as to a hunter of deer. We can see no manner in which it would be any less dangerous for an antelope hunter than a deer hunter in the same area at the same time.”

The law was considered void, yet Wyoming’s wilderness area access restrictions remained in place for non-resident big game hunters even as the Wilderness Act was gaining steam throughout the country.

In order to get a better understanding of why, I asked a Wyoming Fish and Game public access coordinator. The answer I got seemed intentionally vague, but it boiled down to being in the best interests of hunters who might otherwise get themselves into trouble in a remote wilderness area and ultimately need to be extracted, hopefully alive, by a search and rescue team. In simpler terms, non-resident hunters pose a safety risk to themselves and others in wilderness areas in the state of Wyoming.

If all of this this smells like bullshit to you, you’re not alone. The fact that a mountain climber is free to fall her death 13,000 feet up in the Bridger Wilderness Area in the Wind River Range and there’s no concern over a fly fishermen breaking his ankle in small, remote mountain creek 10 miles from the nearest help in the Gros Ventre Wilderness suggests that big game hunters are being singled out for reasons other than safety.

There is simply no hard evidence that supports the idea that big game hunters are at greater risk than any other wilderness area user group.

In fact, a Minnesota big game hunter challenged the law in a 1985 Wyoming Supreme Court case after he was charged for hunting without a guide in a Wyoming wilderness area.

“Keiran W. O’Brien (appellant) was convicted, and fined $100 by a justice of the peace for Park County, on January 18, 1984, of hunting in a federal wilderness area unaccompanied by a licensed professional guide or resident guide, in violation of W.S. 23-2-401(a) and (b).1 ”

In order to make a decision, Wyoming’s Supreme Court was required to answer the following three questions:

- “Does Wyoming Statute Section 23-2-401(a), requiring non-resident big game hunters who hunt in federal wilderness areas to employ guides violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution?” The Equal Protection Clause forbids states from preventing the basic rights of United States citizens.

- “Does Wyoming Statute Section 23-3-401(a) violate the Privileges and Immunities Clauses of the United States Constitution?” The Immunities Clause states, “The citizens of each state shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states.”

- “Does Wyoming Statute Section 23-2-401(a) violate the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution because it conflicts with the purposes of the National Wilderness Preservation System Act and federal regulations thereunder?” The Supremacy Clause mandates that states are bound by and subordinate to the Constitution and federal law.

O’Brien lost his argument that the law is unconstitutional.

The court ruled that, “Perhaps there are some non-resident hunters who are fully capable of looking out for themselves in particular areas and pose no problem to enforcement, but it is reasonable to conclude and more likely that they should have help.”

It also agreed with an earlier district court decision that stated, “Hunting is a recreational sport and not a fundamental right. In such cases the Privileges and Immunities Clause did not come into play, and there was no constitutional violation in that regard.”

Still, it’s a long, commonly accepted, badly kept secret that the law is not designed to ensure the safety of non-resident big game hunters, but in fact exists to line the pockets of Wyoming’s outfitters and guides. It’s no coincidence that the big game and trophy animals an out-of-state hunter is most likely to pursue in a Wyoming wilderness area are big ticket hunts for outfitters. Meanwhile, there is no guiding market for the dusky grouse that live in wilderness areas right alongside elk, mule deer, bighorn sheep, black bears and mountain lions.

The fact is, Wyoming’s wilderness areas are no more dangerous or remote than those in Colorado or Montana, where non-residents are able to legally hunt big game without a guide. Is it true that some hunters don’t have the necessary knowledge, skills and experience needed for a safe, do-it-yourself wilderness hunt?

Sure, but most of the hunters I know have been doing just fine on their own in wilderness areas from Arizona to Alaska. And the roads that run through the national forest, BLM and state lands where non-residents are legally able to hunt big game without a guide in Wyoming don’t necessarily equate to a safer hunting experience. On the contrary, they allow some hunters who aren’t prepared for a backcountry hunt in dangerous terrain easier access to remote areas where they have no business being in the first place.

Perhaps even more importantly, the actual intent of the law seems very clear. Denying access to a specific group of users unless they pay for the experience while allowing free reign to every one else seems like, if not a direct violation of the Constitution of the United States, at the very least a case of blatant pandering to a special interest that stands to benefit financially from the regulation.

Interestingly, there are those who believe Wyoming’s 2012 constitutional amendment that guarantees the right to hunt, trap and fish might be a path towards challenging the 1985 determination that hunting was not a fundamental right and the decision to maintain non-resident hunter wilderness area restrictions. The theory merits a closer look, but a legal battle would be complicated with no guarantee of the statute being overturned.

It is important to note that Wyoming is an extremely hunter-friendly state with some great public land opportunities. I’ve hunted big game there multiple times as a non-resident and I’ll continue to do so in the future.

I just wish I was able to legally hunt the state’s 3 million acres of wilderness without being forced to pay for a guide or acquire the help of a resident. It’s land that I own, along with every other American citizen.

I’ve got nothing against Wyoming’s outfitters. I was a guide myself for many years and I know the value they provide to many hunters, but I’d like the freedom to experience those places and those hunts on my own, just like I can everywhere else.

Feature image via onX.