No matter where you live and hunt, you probably dream of pursuing game animals that aren’t available in your home state. Hunting naturally encourages a desire to explore new areas, whether it’s a trip to Montana for elk, Kansas for whitetails or Florida for turkeys. Many hunters manage to make those dreams into reality on an annual or semi-annual basis. For others, the cost of a non-resident hunting license is too much of a financial barrier to overcome.

Many hunters question the huge disparity between resident and non-resident license fees. When you look at the actual cost differences in many states, it’s easy to see why. A Montana resident pays just $85 for an annual sportsman’s license that includes deer, elk and bear tags, along with an upland bird permit and fishing license. Another $25 gets residents a turkey tag and an antelope permit. Meanwhile, a non-resident pays $1041 for a deer/elk combo license, or $625 and $885 each for deer and elk tags respectively.

In Kansas, a non-resident deer permit will set you back $500, but residents can buy a lifetime hunting license for about the same price. Nebraska sells spring gobbler tags for $109 a piece to non-residents, while residents pay only $30. It’s not just hunting licenses either; non-residents pay much more for fishing licenses as well.

Why do so many states charge non-residents so much more than residents? There’s not a simple answer to that question, but remember that non-resident hunters don’t vote or pay taxes in states they don’t live in. Therefore, out-of-staters don’t have a say when it comes to setting license fees. It’s a seller’s market based on supply and demand. For instance, the demand in Colorado for non-resident elk tags is such that Colorado is able to charge non-residents more than ten times what they charge residents.

Some hunters feel that if they’ll be hunting on federally managed public lands, license fees should not be based on state residency. It’s more complicated than that, though. The BLM and U.S. Forest Service are federal land management agencies, not wildlife management agencies. It’s a very important distinction. A herd of elk may live their whole lives in the White River National Forest, but the State of Colorado pays to manage and maintain those animals.

Wildlife management is largely controlled by individual state governments. This system is known as the Public Trust Doctrine, which is an essential element of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The Public Trust Doctrine grants state governments the sovereign authority to manage fisheries, wildlife and water resources for the benefit of the public.

This trustee relationship was established in 1876 by the McReady vs. The State of Virginia Supreme Court decision concerning oyster fishing rights. McReady was a Maryland resident fishing in Virginia waters. In layman’s terms, the court deemed that oysters were a property right of the people of the state of Virginia and that non-residents had no legal claim to the resource. Later, a 1917 New York court decision involving a beaver damage claim on private property defined wildlife as a public trust to be managed for the state’s citizens.

In turn, managing wildlife as a renewable resource comes with a significant cost to state fish and game agencies. Since each individual state shoulders the lion’s share of the cost associated with maintaining wildlife populations, hunters who don’t live and pay taxes in those states are expected to pay more for the opportunity to take advantage of those resources.

It’s also important to remember that hunting is a privilege, not a right. No state is legally required to allow non-resident hunting, let alone provide cheap, easy access to the game resources they pay to manage. This is especially true in places like Alaska, where game is managed as a source of food for the state’s residents, and in Western states, where big game herds can sustain only a limited amount of harvest.

Some states are stingier than others when it comes to non-resident tag allocation. New Mexico, a place well-known for trophy bull elk and pronghorn antelope, sets aside only 6 percent of available tags for non-residents. This ensures demand will always exceed supply, regardless of price. Elsewhere, from Maine moose to Iowa whitetails, residents are given first priority for availability and cost of hunting licenses.

However, there are important financial incentives for states to provide hunting opportunities for non-residents. Visiting hunters not only support jobs and local economies, but the sale of non-resident hunting and fishing licenses are one of only a few reliable sources of funding for state agencies.

These agencies are often operating with annual budgetary shortfalls. Higher non-resident license fees are one way for these departments to keep some gas in the tank. In many western states, non-residents directly contribute more to fish and game budgets than residents do.

Last year, Colorado Parks and Wildlife banked $38 million from non-resident deer and elk license sales compared to $7.6 million from resident hunters. Despite this massive annual influx of revenue, the agency is still underfunded. According to Jason Blevins from the Denver Post, “CPW has cut or defunded 50 positions and reduced $40 million from its wildlife budget since 2009 to address funding shortfalls.” In 2018, Colorado’s legislature passed a bill to increase resident license fees in order to help offset these deficits.

What’s happening in Colorado is happening all over the country. State fish and game agencies need to secure funding wherever they can in order to keep providing enjoyable outdoor experiences. In some states, high non-resident license fees aren’t the only, or even the best, solution. Increasing resident license fees has also become an increasingly necessary measure.

Consider Montana, where extremely low resident license fees do little to adequately fund management agencies, while high non-resident licenses have driven away some hunters. In recent years, hundreds of non-resident Montana general deer and elk tags have gone unsold after the initial application period, indicating higher prices are causing a drop in demand.

Not every state puts the screws to non-resident hunters. In Pennsylvania, a non-resident can buy an annual hunting license for around $100. This includes your small game license, spring and fall turkey tags and a buck tag. In Maryland, a few dollars more allows a non-resident hunter to harvest multiple whitetails and sika deer, plus small game and wild turkeys. All over the Midwest and Southeast, hunters can find affordable non-resident whitetail, turkey and small game licenses. Even in the West, there are overlooked and affordable big game hunting opportunities.

Unfortunately, high non-resident license fees are here to stay. Hunters who want to make an out-of-state hunting trip need to decide if the cost of a hunting license is a worthwhile investment. I go on at least one out of state hunting trip every year and to me, the answer is always yes.

The money you spend on a non-resident license could provide a year’s worth of meat and a lifetime’s worth of memories. I guarantee you’ll never regret going on an out-of-state hunting trip but you’ll definitely regret having never gone at all.

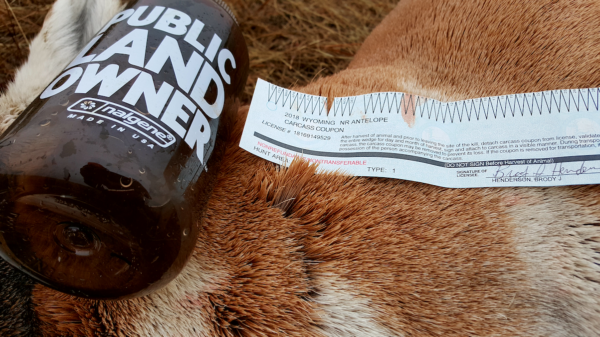

Feature image via Garret Smith.